Irish Jewel Of Cleveland: The Great Johnny Kilbane

By Mike Casey

Boxing, if taken from its earliest days in all its shapes and

forms, is probably the richest and most diverse sport of all, full of goldmines

and gold nuggets, a glorious and unruly slab of history with countless different

offshoots and mysterious little alleys. Just as eager astronomers continue to

discover new galaxies and new planets, so we continue to mine the lost and

hidden treasures of our own little kingdom and unearth new jewels. Somebody

discovers another Jack Dempsey fight that has been buried in the mists of time.

Somebody else comes up with a fresh story about a famous fight that we thought

we already knew everything about.

Where fighters of a bygone age are concerned, especially those

who are only able to show us their great talents on snatches of old and grainy

film, we can only study form and reach what we believe to be a fair summation of

their historical standing. Then we stumble across something that causes us to

rethink. Just recently, I was reading an old book by Denzil Batchelor, a popular

and respected British boxing reporter of the forties and fifties, and came upon

his opinions of the featherweights who reigned before the Great War. Up came the

name of Johnny Kilbane, the Irish wonder from Cleveland, Ohio. Ah-hah, I

thought, this should be interesting. Why? Because I have always had a little

trouble getting a real handle on Mr Kilbane. Such was Johnny’s cleverness that

so often in his career he would coast and clown and only do as much as he had to

do to win. Judging such fighters is always something of a headache, since one

can only give them so much leeway in regard to how much greater they MIGHT have

been if they had really stepped on the gas.

I remain convinced that the three greatest featherweights, all

factors considered, were Jem Driscoll, Willie Pep and Henry Armstrong, and I

really don’t have much of a problem about the order in which those three

geniuses are placed. But where does Johnny Kilbane fit in what we might call the

second tier? Was he better than Attell, McGovern, Johnny Dundee, Kid Chocolate,

Vicente Saldivar or Alexis Arguello?

Denzil Batchelor wrote his book in 1954, which of course was well

before the times of messrs. Saldivar and Arguello, but the author’s estimation

of Johnny Kilbane still surprised me. Here is a paraphrased version what

Batchelor said: “The greatest of American feathers before the Kaiser’s war was

unquestionably the brilliant Johnny Kilbane, who defeated Abe Attell in 20

rounds in 1912 and held the title for eleven years till beaten by Eugene Criqui.

“Kilbane, of Irish descent, came from Cleveland. It took him five

years to win the championship; by which time he had lost only twice: once to

Attell and once to the Mexican pepperpot, Joe Rivers. He was fast, clever,

brilliant at close quarters and a destructive puncher judged by the highest

standards. After he had won his title, he lost only two contests in eleven

years. The pity of it is that Driscoll visited the States before Kilbane had

matured. If the two had been exact contemporaries, the history of the

featherweight division would have been enriched by their rivalry. There never

was a better featherweight than Johnny Kilbane of Cleveland, Ohio.”

It is here that we run into the usual wall of frustration, since

we will never know whether Johnny Kilbane was truly one of the supreme talents

of his weight class. But here is something else that gave me a jolt. When you

trawl back through Johnny’s achievements by way of countless newspaper reports,

there is a recurring theme of unstinting praise for his ring skills. Hard-nosed,

genuine boxing writers, well seasoned and not inclined to purple prose, clearly

struggle to find the appropriate superlatives for the Fighting Mick of the

featherweights. On more than one occasion Kilbane is described as the ace of all

fighters, which is praise indeed when one considers that his long reign as

champion bridged the eras of Jack Johnson and Jack Dempsey.

Outclassing Abe Attell

Speaking of long reigns, it seemed that Abe Attell had been the

featherweight champion since the days when a despairing Abe Lincoln was saying

of General McClellan, “If he is not using the Union Army, I should like to

borrow it.”

Abe Attell, the wonderful Little Hebrew, was the so-called

dancing master, fast and crafty as a fox, tough and courageous. Only Peerless

Jem Driscoll had truly mastered Attell in the pure boxing stakes, trimming Abe

very neatly in their classic New York encounter of 1909. Abe had seen off all

other challengers and it seemed that he might just chug on forever. Then he

defended his championship against the young and devilishly evasive Johnny

Kilbane and must have thought that Driscoll had come a-haunting in a different

guise. Johnny didn’t just take Abe’s title. He absolutely cleaned him, and

referee Charles Eyton had no hesitation in raising the challenger’s hand at the

finish. Attell couldn’t believe his defeat and certainly could never accept it.

The veteran and the new kid on the block clashed over 20 rounds

at the Vernon Arena in California on February 22, 1912. Nearly ten thousand fans

crammed into the venue, where the capacity was 8,400. A further five thousand

failed to get past the gates and were turned away. The gate receipts totalled

around $25,000, a formidable total at that time. Johnny and Abe fought for a

$10,000 purse, of which it was agreed that Attell would receive $6,500

irrespective of the result. The fight was filmed and the boys also agreed on an

even split of the motion picture privilege.

For Abe, the result was a stunning reversal. The skill and guile

that had seen him reign for years was sadly infrequent against Kilbane,

suppressed by Johnny’s speed and cleverness and by Attell’s ageing legs.

Abe was very nearly shut out of the fight, one ringside reporter

only according him the seventh round. Attell never got out of the starting

blocks and then he began to panic as his prized crown began to slip from his

grasp. Desperation gripped him as the battle wore on and his efforts to turn the

tide failed. He resorted to fouling, a tactic that didn’t go down at all well

with his supporters. He locked Kilbane’s arms in the clinches, heeled him on one

occasion and tried to bend his left arm back on another.

If Abe believed his fans would turn a blind eye to his actions,

he was mistaken. Boos and hisses filled the air as the old campaigner worked his

way through his box of dirty tricks. Attell had plenty to feel angry about. The

erstwhile boxing master was being repeatedly struck by a relentless flow of

accurate punches from the young Irish upstart. In the sixteenth round, with no

great attempt to mask his intentions, Abe surged into a clinch and butted

Kilbane so severely that Johnny sustained a deep gash over his left eye. Blood

oozed from the ugly wound but the inconvenience failed to check Johnny’s

inexorable march to the championship.

Abe’s mood had already worsened at the beginning of the round,

after referee Eyton had grabbed a towel and wiped a liberal coating of grease

off the champion’s body. Abe and his handlers, it seemed, were trying an

alternative way to slip punches. But Johnny Kilbane was the big story on this

day, even if the great Attell was finally slipping over the hill. Even Johnny’s

backers marvelled at the authoritative manner in which their man put Abe under

the cosh and never let him up for air. The youngster was incredibly fast with

his hands and feet and couldn’t seem to miss Attell with a persistent stream of

solid, straight jabs. Right crosses repeatedly hit the champion with speed and

force. Such was the quality of Kilbane’s footwork that even the usually graceful

Attell was often made to look crude and ungainly.

From the outset to the finish, wise old Abe laid traps that

yielded no prize. He tried to feint Johnny, he tried to corner him, but the

young ace avoided all the potential pitfalls with the untouchable air of a

ghost. The decision for Kilbane was a popular one and greeted enthusiastically.

Johnny was carried from the building on the shoulders of his friends, telling

them that he wanted to telephone his wife.

Attell left the ring on his own, no longer the world champion,

no longer the man everyone wants to talk to. Spotting a friend, Abe said, “Well,

I had to stand for it. I couldn’t do any better.” It seemed a philosophical

acceptance of the inevitable on Attell’s part, yet his dethronement – and Johnny

Kilbane personally – would rankle with Abe for the rest of his life and fill him

with bitterness.

The truth is, Attell let himself down badly with his spiteful

rants, often sounding like a spoilt and resentful child. Kilbane had set him a

puzzle and Abe had failed to solve it. His warped conclusion was that Johnny had

stolen the title by unfair means. “Kilbane should have been ashamed of himself,”

Attell complained. “He was the challenger but he wouldn’t do anything but lay

back and play it cute. I would have made the fight but I couldn’t go forward, my

legs were gone.”

But that wasn’t all. It was also Abe’s contention that Kilbane

had tried to poison him by way of the fumes from the chloroform that Johnny’s

handlers had apparently rubbed into his body.

Forty years later, Attell was still raging when he bumped into

Kilbane at Madison Square Garden. It wasn’t your average social reunion. “I’d

like to punch you in the nose right now,” Abe said. Kilbane apparently laughed

and left it at that.

As Irish As Paddy’s Pig

According to boxing writer JP Garvey, Johnny Kilbane had jammed

43 fights into just three-and-a-half years’ campaigning by the time he dethroned

Abe Attell. Garvey was impressed by the new star of the featherweights and

wrote, “Johnny Kilbane, as Irish as Paddy’s pig, a 22-year old boy with

sparkling eyes, ready wit, whose every action is peppery, effervescent,

indicative of a lightning brain and panther body, is the successor of Abe Attell

as the featherweight champion of America. A boy better equipped for this

estimable honour would be hard to find.

“With him as leader, the scientific standard of proficiency

introduced by George Dixon and furthered by Attell will not suffer. Rather it

will be improved upon to the betterment of the boxing game.”

Kilbane had an engaging personality and a sharp sense of humour.

He was born in Cleveland to Irish parents and JP Garvey couldn’t help waxing

lyrical about the influence of Johnny’s spiritual homeland. “He has no brogue

but you can tell his ancestors had. There is something about him – perhaps it’s

his flashing eyes and a general air of activity which he can’t control – that

suggests shamrocks in full bloom, the bogs, the turf, the clay pipes and the

black tea.”

From his teens, Johnny Kilbane was a tough little customer. He

simply had to be. His father went blind and Johnny was hurried through school so

that he could go out to work and support his family. He was around thirteen or

fourteen when he got a job as a switch tender on the New York P&O railroad. He

weighed little over 90 pounds but quickly became known as a live wire who loved

to fight. Johnny spent his evenings hanging out with boxing fans at the

appropriate watering holes and loved to listen to them discussing the fights.

The young Kilbane soon began to fantasise about a career as a professional

fighter, imagining glorious victories and the cheers of big crowds.

Switch tending on the railroad paid a steady wage but it wasn’t

the way to spend the rest of your life. Johnny quit after a year. The boxing bug

had bitten him hard. Jimmy Dunn, a crack lightweight of the time whom Kilbane

idolised, was training at Crystal Beach and Johnny went to watch him. He and

Dunn became good friends and Dunn willingly gave Kilbane boxing lessons, later

becoming Johnny’s manager.

Kilbane fought his first professional fight on December 2, 1907,

and had no trouble getting matches for the first six months of his career. But a

lean period followed, during which time Johnny often found it hard to get three

square meals a day. The tough times failed to dampen his enthusiasm. He studied

the Noble Art all the time, eager to learn more and improve his toughness and

technique. His natural love and talent for boxing made him a quick learner. The

first big year for Johnny was in 1909, when ring work became plentiful again and

he started mixing with quality fighters such as Jack White, Johnny Whittaker,

Biz Mackey and Happy Davis.

Kilbane’s style was a double-edged sword that drew its share of

critics. His great skill and speed, not to mention his general ring cleverness,

became universally acknowledged, but even his friends felt that he was too much

of a ‘runner’. Kilbane proved that he could knock opponents out as well as

out-fox them over the long haul, but he failed to shake the conviction of many

that he was, in the parlance of the day, a ‘looking glass’ boxer. Johnny’s cause

wasn’t helped by the presence of another ‘Kilbane’ on the boxing scene. The

undefeated Tommy Kilbane, also out of Cleveland, was much more of a fan’s

favourite with his aggressive, hard-hitting style. He and Johnny had already

clashed three times , with Johnny holding the advantage in their closely

contested series. The two boys decided to settle the question of supremacy and

it was Johnny who won the day by a decision when they battled at Canton, Ohio,

on New Year’s Day in 1910.

Nevertheless, Kilbane continued to be a ‘grey’ fighter to many

fistic observers. Very skillful, yes. World class, undoubtedly. But could the

kid marry all that fancy stuff to a knockout wallop against a top notch

opponent? The fight that caused many of Kilbane’s critics to revise their

opinion of him was his smashing triumph over Mexican Joe Rivers at Vernon,

California, on September 4, 1911. Rivers had already taken a 20-rounds decision

off Kilbane in their first fight four months earlier, a defeat that hurt Johnny.

He took a great pride in being one of the ‘Fighting Irish’ and felt he had let

his side down. In the early rounds of their return match, Mexican Joe, a

powerful and natural fighter, again proved to be a tough proposition. A fast and

often furious puncher, Rivers had little trouble in tagging the speedy and

elusive Kilbane. The stinging blows that struck Johnny only served to harden his

resolve as he turned hunter and waited for the chance to outpunch the puncher.

The end came with shocking suddenness in the sixteenth round, when he drilled a

tremendous right to Mexican Joe’s chin and knocked him out.

The Eternal Champion

By 1921, Johnny Kilbane had been the featherweight champion for

nine years, having mastered the division in much the same dominant fashion as

Abe Attell had done before him. Johnny had now won the respect of fans and

writers everywhere and was approaching near legendary status. He had become

almost a part-time fighter, devoting much of his time to buying and selling real

estate. But the cartoonists still loved to remind people that this was the

phantom with a punch who had made Abe Attell look foolish. Abe’s caricature

would invariably be seen swiping furiously at thin air, and how that must have

hurt the Little Hebrew.

But Kilbane was now fading and losing his desire for ring

warfare. Ace writer Bob Edgren had seen the hunger slowly go out of 31-year old

Johnny, so much so that the champion was able to turn down an offer of $30,000

from Tex Rickard to fight any challenger of choice. Wrote a somewhat

disenchanted Edgren: “I have no trouble remembering the time when Johnny would

have been glad to fight any featherweight in the world for fifteen hundred or

for the fun of it. If Kilbane was Kilbane, he’d do it now.

“Johnny may be fair, fat and thirty-one today, but he was the

genius and original ‘Fighting Mick’ when he beat Abe Attell. Surest thing you

know, that boy could fight anything from a Mexican wildcat to a grizzly bear and

get away with it. He had a poke like a lightning bolt and a sidestep that made

his opponents miss more swings than there are on all the gates in the county.

Talk about a dancing fool! That was Johnny Kilbane when he felt like dancing. He

could hop, skip and jump around a ring in a way that would make Johnny Dundee

look like a loaded truck trying to go up Fort Lee Hill on an icy morning.

“They couldn’t hit Kilbane with a bucket of birdshot, and that’s

all there was to it. He invited punches and when they arrived he simply wasn’t

there. And all the time he was slapping and tapping and laughing and chatting,

and making a monkey out of the earnest young man in front of him until people in

the front row laughed so hard they fell out of their seats. Yes, when he wanted

to, Kilbane surely could fight.”

Edgren was not wrong. It was a recurring theme of Johnny’s career

to remind people with a jolt of his ability to seek and destroy when he needed

to. A good way into his featherweight reign, Kilbane was moving along nicely and

outpointing challengers without fuss or frills. The fans were getting a little

bored with the safety-first champ. Then a man known as the Knockout King made

the mistake of upsetting Kilbane. George (KO) Chaney, as hard a pound-for-pound

puncher as there ever was, secured a crack at Johnny’s title after Chaney’s

manager had baited Johnny in the sports pages for quite some time.

“They think I can’t hit any more,” Kilbane said in a letter to

Bob Edgren. “I can hit harder than ever, but I always prefer winning on points

because I don’t like to risk hurting anybody. This time I’m going to let the

punches go, and I’ll knock this fellow Chaney out in a hurry.”

Kilbane was true to his word. He gave George (KO) Chaney two

rounds to show his wares and then knocked out the Baltimore challenger with a

single shot in the third.

Downed By The Ghetto Wizard

Kilbane had talked about retirement as early as 1917, when he

made what has often been described as the only major mistake of his career.

Johnny got it into his head that he could step up to the lightweight division

and take Benny Leonard’s crown. Great as Johnny was, this was a foolish notion

as Benny, the slick and dapper Ghetto Wizard, was even greater as well as bigger

and stronger. He knocked out Kilbane in three rounds at Philadelphia and

Johnny’s manager, Jimmy Dunn, said, “There was nothing to do but throw in the

towel. I never saw Johnny fight the way he did last night. He was badly beaten.

If I’d sent him out again it would have been to have him take a worse beating

than a knockout and I didn’t want to see him beaten up. This is his last fight.

I’ll never send him in the ring again. As far as I am concerned, Johnny is

through and will retire with his title.”

Benny Leonard’s sparkling performance confirmed his standing as

possibly the greatest of all the lightweight masters. As one reporter noted,

“No man, lightweight or featherweight, has ever been given a higher rating than

Kilbane. Champion in his own class, four times he has stepped into a ring

against another champion and three times he has come off victorious. The last

time was last night when he failed.”

But Johnny boxed on, of course, as most great champions

invariably do until they receive that final and irrefutable confirmation that

the well has run dry. Some two years before French war hero Eugene Criqui ended

Kilbane’s astonishing reign, Johnny painted his last masterpiece in Cleveland.

There, on September 17, 1921, he gave another stirring example of how he could

turn off the smiles and turn on the power.

Danny Frush, despite a brave and courageous challenge, had

already been decked twice by the time he came out for the seventh round to take

another Kilbane fusillade. The two fighters rushed to the centre of the ring and

Johnny landed a left to the face. Frush then went down for a third time from a

left to the jaw, getting up slowly at the count of nine. He was quickly down

again from a succession of lefts and rights to the jaw and now in disarray from

being hit and generally bedazzled. Unsteady, Danny swayed into the ropes and

received terrific punishment from further rights and lefts to the face. He fell

from the ropes to the canvas, where he remained as the referee counted him out.

Oh yes, Johnny Kilbane could dance alright. He could also kick

like a mule when the mood took him.

Postscript

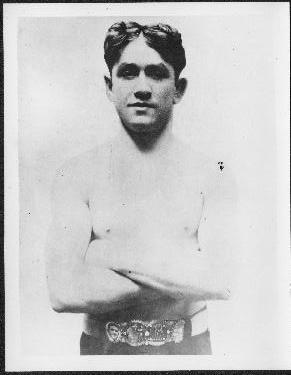

My sincere thanks to Kevin O’Toole for allowing us to publish the

picture of Johnny Kilbane that accompanies this story on the CBZ Newswire.

Please check out Kevin’s excellent website on Johnny at

www.johnnykilbane.com

> The Mike Casey Archives

<

|