Twice in a

blue moon! When Sonny Liston and Jerry Quarry were KO’d in the same month

By Mike Casey

If three brave and pioneering astronauts believed that they had a

lock on thrills and spills for the year of 1969, they reckoned without the

unpredictable world of sports. While Neil Armstrong, Edwin ‘Buzz’ Aldrin and

Michael Collins were taking one giant leap for mankind on the moon, some

distinctly unworldly events were beginning to unfurl back home on the blue

planet.

One wondered where the madness came from and how long it would

last. It began in May, when basketball’s New York Knicks, a charter member of

the NBA and still in search of their first league championship, had the temerity

to knock off the stately LA Lakers by four games to three in the NBA finals.

Normal life was further dismantled by baseball’s lowly and long

suffering New York Mets, who came along in the fall to win the World Series over

Baltimore. For those of you who don’t have an interest in such pursuits, these

things are not supposed to happen. Even New Yorkers will reassure you on that

point.

The natural order of things had been turned inside out and one

sensed that there was more to follow. Such cataclysmic events are supposed to

come in threes after all. But even trusted old adages were discarded and tossed

out of the window as the sporting world was torn apart and re-arranged by a

mischievous hurricane that refused to blow itself out. There would be four bolts

from the blue in all before the sixties died and the seventies dawned.

It seemed entirely fitting that the stage was left to

professional boxing to set off the last couple of explosions. The old game

waited patiently until December before plucking two of its premium heavyweights

out of the hat and giving them a very rude and sobering Christmas.

The big blows came only six days apart, like a good old-fashioned

one-two. On December 6, at the International Hotel & Casino in Las Vegas, the

last vestiges of Sonny Liston’s mythical invincibility were brutally erased by a

single blast to the jaw from Leotis Martin. On December 12, at Madison Square

Garden, Jerry Quarry somehow contrived to get himself knocked out by George

Chuvalo.

To those youthful and lucky souls who can boast that they were

not even born in 1969, I can only say that those two results were more shocking

than you can ever imagine. It was akin to being told (as indeed we subsequently

were by the usual mischief makers) that Neil, Buzz and Michael hadn’t gone to

the moon at all, but had simply been larking around on a cunningly disguised

film stage.

Impact

To fully appreciate the full impact of that crazy December, it is

first necessary to turn the spotlight on Leotis Martin and George Chuvalo.

Leotis and George were two of the great heavyweight plodders, but

with potent additives. They were dangerous plodders, capable of the

extraordinary at any given time. They never gave up, they never stopped trying,

they never stopped believing that tonight would be their night. Both men had too

many limitations to ever attain greatness, but inhibition was not among their

flaws. Martin and Chuvalo were fringe contenders who could never quite step over

the line and join the elite. They had been hardened by that certain brand of

mental toughness and disdain that comes from repeatedly being knocked back into

line. Far from feeling humbled by adversity, Leotis and George acquired the

simmering bloody-mindedness that so often finds its voice at the unlikeliest of

times.

Chuvalo’s standing in the game was almost unique for a man who

lost the vast majority of his big fights. Astonishingly tough and durable, he

achieved the rare dual status of world class contender and trial horse by being

consistently competitive and just occasionally turning the form book upside

down. In between times, George would pad his record by knocking out a succession

of lesser fighters. He was the perfect opponent for Jerry Quarry in 1969, and

indeed for most of the top ranked contenders at any other time. Chuvalo was

ideal: a top ten contender, a good draw at the box office, a respectable name to

have in your win column. All the top guys knew that good movement and a

persistent jab would always see off old George from Canada. Nearly always!

Chuvalo was what the game calls a catcher, and he was catching

big time from his early days as a pro. Like a great water bison, George was

dangerous if he could suck you into his bulling and slugging domain, but the

smarter boxers knew that he could be easily speared and out-paced. Chuvalo even

dropped a decision to the former Olympian Pete Rademacher, who was adhering to

his curious game plan of starting at the top and working steadily downwards. In

his first professional fight, Pete had famously challenged Floyd Patterson for

the championship and had also been blitzed by Zora Folley and Brian London

before mastering Chuvalo.

George toiled for eight years before he tore up the script and

pulled his first shocker. In a thrilling finish at Madison Square Garden in

October 1964, he attained his special place among the leading heavyweights by

stopping Doug Jones in the eleventh round. Even Rocky Marciano took an interest

in the rough and tough body puncher who had seemed to suddenly catch fire.

But George would always be a dangerous nearly man, which was why

he remained so fascinating. Competitive defeats to Patterson, Ernie Terrell

Muhammad Ali and Oscar Bonavena over the next couple of years served to keep

Chuvalo in the picture, but he seemed to be skidding seriously when Joe Frazier

became the first man to stop him inside the distance in 1967.

With typical defiance, George rallied to score a fifth round TKO

over Mexican contender Manuel Ramos in 1968, but it was a victory that flattered

to deceive. Ramos had also been savaged by Frazier and there were many who felt

that Manuel’s high ranking was far too generous.

Coming into the Jerry Quarry fight, George was treading water and

going nowhere. He had scored a couple of meaningless wins over Stamford Harris

and Leslie Borden, but had been bloodied and outpointed by Buster Mathis in his

last fight of real importance. Quarry, it seemed, was going to have a field day.

Philadelphia

Leotis Martin had been hewn from the tough school of Philadelphia

boxing and was thirty years of age when he got the chance of his life against

Sonny Liston in Las Vegas. Dame Fortune had never smiled kindly on Leotis. He

didn’t get the breaks and he didn’t get the odd decision or two he might have

deserved. When he knocked out Sonny Banks in a 1965 match, Banks subsequently

died from his injuries. Cruel luck would haunt Leotis to the end, for even his

greatest accomplishment would be soured by his greatest frustration.

Just as George Chuvalo appeared to fit like a glove for Jerry

Quarry, so Martin seemed tailor made for the creaking but still formidable

Liston. Leotis could box and he could punch, but the one thing he couldn’t do

was seriously inconvenience the top men of the division. He had been

outmanoeuvred and stopped by Jimmy Ellis and out-bulled by Oscar Bonavena.

Martin had carved out a respectable 30-5 record and his eighteen

knockouts were testament to his power. Turning professional in 1962, the year in

which Liston won the championship, Leotis had recovered well from a rude

awakening in his tenth fight, when he was knocked out in two rounds by Floyd

McCoy.

Like so many quietly dangerous journeymen, Martin took fights

wherever he could get them. He fought Bonavena in Beunos Aires, knocked out the

fading Karl Mildenberger in Frankfurt and came from behind to stop Thad Spencer

in an absolute thriller at the Royal Albert Hall in London.

Martin’s credentials were solid without being spectacular when he

shaped up against Liston. Leotis was on a good run of four straight wins,

including a couple of quality victories over that other dark horse, Alvin ‘Blue’

Lewis.

With the priceless gift of hindsight, it is easy to say now that

Sonny Liston was heading for a big fall. Sonny was slowing all the time and was

no longer the killer of his prime who got the job done quickly. Now his fights

were beginning to draw out longer as the old bear paced himself and used his

pole-like jab to break down opponents at a more leisurely rate.

Yet still there was a grand and almost imperious mystique about

Liston. His reputation had been all but shredded in his bizarre fights with

Muhammad Ali, to the point where Sonny found it impossible to obtain a license

to box in his native land. Ring editor Nat Fleischer famously told him,

“Frankly, you are the forgotten man.”

Yet as time moved on, it was those infamous fights themselves

that seemed to be forgotten in the minds of many Liston supporters, as denial

applied its blinding grip. Burned into my memory is the letter of one shocked

fan after witnessing Sonny’s incredible collapse against Ali in the great

Lewiston fiasco. “I may be a voice in the wilderness,” the fan wrote, “but I

still think Sonny Liston can beat Muhammad Ali!”

In truth, Sonny had been getting away with it for a lot longer

than most people ever knew. In the parlance of the trade, he was always a bad

trainer. In the run-up to his second fight with Patterson, Liston was seen more

often around the Las Vegas crap tables than he was in the gym. He trained poorly

for the first Ali fight at Miami Beach, eschewing heavy boots to do his running

in sneakers. For the second fight, according to one observer, he could barely

skip rope.

What we will probably never know is the extent to which Liston

abused his body in other ways. He certainly enjoyed lacing his soft drinks with

the hard stuff and might well have eased his constantly troubled mind with more

adventurous potions. One only has to look at the vastly conflicting reports on

the circumstances of his mysterious death in 1970 to appreciate the danger of

surmise. Many stories about Sonny Liston were true. Many others were plainly

absurd.

What is undeniable is that Liston was a fighter in decline from

as early as the Patterson fights. By the late sixties, as he awaited a slim

second chance at glory, Sonny was plainly being protected by some prudent

matchmaking. Back stage, the alarm bells were becoming too audible to be denied.

During one sparring session, he was reportedly knocked cold by Fresno puncher

Mac Foster, whose own limitations would later be exposed by Jerry Quarry.

Daunting

For all that, Liston remained a daunting proposition for the

majority of would-be contenders and he got off to an impressive start against

Leotis Martin. Sonny still possessed the intimidating air of a big grizzly and

Martin was shrewd enough not to bait the old man in the early rounds. Leotis was

making Sonny chase him, countering when possible, but looking for the most part

like a capable journeyman heading towards honourable defeat.

That impression gathered momentum when Sonny decked Leotis for a

mandatory eight count in the fourth round. By the end of the fifth, Liston had

accumulated a substantial points advantage and was apparently cruising. But age

and laziness had come to collect their dues and were now eating into Sonny’s old

body by the second. The sixth stanza was one of those strange, tell-tale rounds.

Nothing overly dramatic happened, but suddenly Liston looked to be tiring as

Martin upped the pace and enjoyed some success with left and right counters.

Leotis was a good old pro who could read the signs, and the signs told him that

Liston could be taken. The underdog was no longer back-pedalling and making do

with slim pickings. He was taking the fight to Sonny and mixing it.

The tempo of the bout increased in the seventh as Martin’s

accurate shots brought blood from Liston’s nose. One wondered what Sonny was

thinking as he headed for the guillotine. Did he sense the end was nigh? Did he

still believe he could make it to the finishing line? In the old days, he didn’t

have to concern himself with such trivia. Few men had dared to cuff him about

and mess him around like this guy Martin.

In the eighth round, Sonny was given a further reminder of his

shrinking status as a man of terror. Trying to turn back the clock, he drove

Leotis into a corner with a barrage of lefts and right to the head and body. The

bully boy was back on the block, putting the young upstart in his place. But

Martin would have none of it. The greatest victory of his life was now within

his reach and he fired back confidently to force Liston back into mid-ring.

Blood trickled from Sonny’s mouth as the welcome bell gave his some much needed

respite. He still had the points in the bag, but now it seemed that the gods

were dragging the end zone beyond his reach.

The ninth round was shocking. Even though the writing was the

wall, one couldn’t quite picture Sonny Liston being knocked out. Not genuinely

knocked out. Against Ali, Sonny had looked like a man having a snooze. Against

Martin, he looked like a luckless pedestrian who hadn’t seen the truck coming.

The two men exchanged hard punches before Leotis hit the jackpot

with a perfectly drilled straight right to the chin. Liston stopped and wavered

slightly as the blow registered. Like one of his beloved casinos being

dynamited, sections of his great body seemed to linger stubbornly in mid-flight

as a following left hook made him lurch sideways and a final right to the jaw

sent him tumbling. Sonny was out. Face down, spread-eagled, dead to the world.

No longer the big bad bear who could defeat opponents before they even got out

of the dressing room. Never again.

Six days

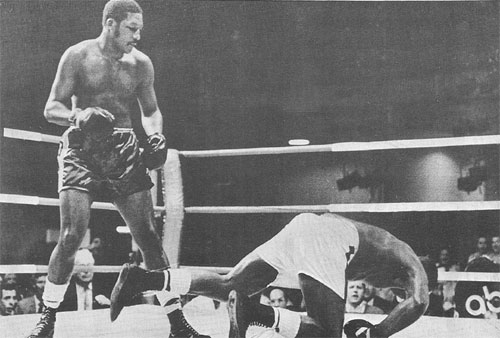

Six days later and six rounds into his fight with George Chuvalo,

Jerry Quarry was imitating Liston and looking like another comfortable

front-runner going through the motions. The reverberations of Sonny’s mighty

fall from grace were still being felt around the boxing globe, but Jerry was no

Sonny. The ruggedly handsome Irishman from Bellflower, California, was young and

strong and still very much on the upswing. He was coming back after a losing but

heroic stand against Joe Frazier in the summer, and a victory over Chuvalo would

serve as a springboard back to the really big fights.

Madness had reigned in Las Vegas, but then Vegas was a mad place.

Logic would surely prevail in the more hallowed and orderly environs of the

Garden. Chuvalo was following the script perfectly, chasing and throwing but

eating too many punches in return to make an impression.

Perhaps George’s very predictability was Quarry’s problem.

Jerry’s mental approach to certain fights was always his Achilles heel. Chuvalo

wasn’t stirring his mind and forcing it to think and work. Take your eye off the

punching bag and we all know how silly it can make you look.

Jerry jabbed and hooked and opened up with an impressive volley

in the fourth round to split George’s cheek open. It was par for the course.

George wasn’t George if he didn’t get banged up and swollen.

Coming up for the seventh round, Chuvalo bore the look of a man

who kept slipping out into the back alley between rounds and getting mugged by

the same gang. But he was scoring with some hurtful wallops of his own as the

round drew to a close and then he tossed the big one. A long left found Jerry’s

temple and caused him to check and dither for a moment before he fell back and

sat down. It didn’t seem too big a deal. Embarrassed by the sudden turn of

events, Jerry got straight up but then took a knee to clear his head and buy

some seconds. His action seemed to be a matter of choice rather than necessity,

but then everything went wrong. As the crowd roared and referee Zach Clayton

picked up the count, Quarry’s attention became scrambled. Before he knew it, the

train he needed to jump on had sped through the station. He still had one knee

on the canvas as the count reached ten. Out!

Nobody could believe it. Not the crowd, not Quarry, and probably

not even George Chuvalo. In his dressing room, Jerry raged at what he believed

to be an injustice. “Nobody knocks me out,” he insisted. “I was looking at the

clock and I couldn’t hear the count because the crowd was yelling so much. I got

gypped. I got ruined. That destroyed me. I could have gotten up. I couldn’t tell

the count by his (Clayton’s) fingers.”

Chuvalo dryly retorted, “If he couldn’t tell nine from ten, it

must have been a good punch.”

Epilogue

When the smoke cleared and some degree of normality returned, the

four players of the crazy December of ’69 went off on decidedly different paths.

Sonny Liston enjoyed a last hurrah as he pounded out a ninth round TKO over the

Bayonne Bleeder, Chuck Wepner, at the New Jersey Armory. Six months later, Sonny

was found dead in his home, the cause never satisfactorily established. He is

buried at McCarren Airport in Las Vegas, where a simple plaque is engraved:

Charles Sonny Liston, 1932-1970, ‘A Man’.

Leotis Martin, the hard luck man from Philly, suffered his

cruellest blow of all in sustaining a detached retina during the Liston fight.

Leotis harboured hopes of carrying on, but the injury forced him into

retirement. He died in 1995 at the age of fifty-six.

Six months after getting knocked out by George Chuvalo, Jerry

Quarry charged to the number one spot in the rankings by wrecking Mac Foster in

six rounds at Madison Square Garden. Jerry remained a top contender for several

more years and enjoyed his finest campaign in 1973 with huge wins over Ron Lyle

and Earnie Shavers. Sadly, Quarry couldn’t leave the game alone and was still

chasing ghosts as late as 1992, his glory days long gone and his health in

frightening decline. He died at fifty-three in 1999 from pugilistic dementia.

But what of George Chuvalo? The old rock from Canada, who took

more punishment than all of them but never took a knockdown, remains

outrageously sprightly and youthful at sixty-eight: still witty, still full of

fight, still meeting up and chatting with old friends and former foes.

The Quarry victory resurrected Chuvalo’s career as a major league

contender, but, reassuringly perhaps, didn’t change the nature of the beast. As

1970 got underway, George slipped effortlessly back into his familiar role of

world class trial horse, bruising men’s fists with his incomparable head.

> The Mike Casey Archives

<

|