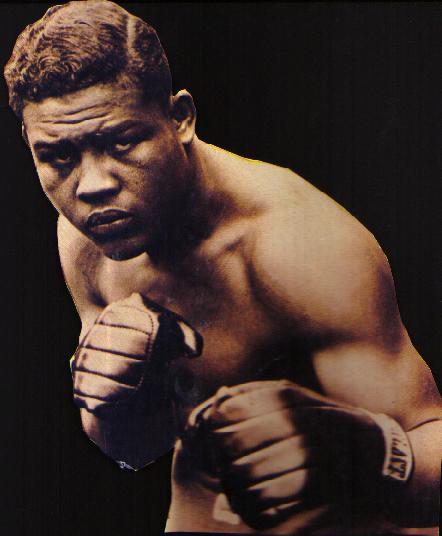

Slaying

giants: Chilling lessons from Jolting Joe

By Mike Casey

Like the little boy who keeps banging his head against the wall

because it feels so good when he stops, I guess I will continue to preach about

punching technique and its many intricacies until the day I die. I imagine too

that I will continue to be countered by those who insist that Jim Jeffries was

an overrated plodder, Jack Dempsey was a crude banger and that David Tua could

knock all the old champs into a cocked hat.

How desperately starved of thrills we were before the Klitschko

brothers came charging over the horizon with assorted puddings and tubs of lard

to back them up! When Rocky Marciano wandered off into the sunset, the only guys

we had to cheer us up and pleasantly shatter our senses were the cream puff

likes of Sonny Liston, Cleveland Williams, George Foreman, Jerry Quarry, Ron

Lyle, Earnie Shavers and Mike Tyson.

Then along came the muscle-bound cavalry of slow-mo androids with

their big biceps and big bellies and other interesting parts that jiggled and

wobbled. Never mind their lack of enthusiasm and their somewhat inappropriate

reluctance to have a fight. These guys could punch because they had muscles like

boulders, super-duper nutrition and because they were…. BIG!

Well, if white men can’t jump, then big men don’t move around too

easily and precious few of them can punch their full weight. In my lifetime, the

very special talent that was the young, 220lb George Foreman was the only ‘super

heavyweight’ who could hit like the wrath of God and scare opponents with his

shadow. That particular Foreman, of course, would not be a super heavyweight in

the present era. He would be described as ‘small’, even though I believe that he

would wreak just as much havoc. Indeed, I would confidently wager my limited

possessions on George very quickly butchering Nikolay Valuev and needing less

than four rounds apiece to decimate the Klitschko duo.

Giants in boxing have consistently been members of a curious

breed. Rarely are they natural fighters or, more importantly, natural born

killers. It doesn’t require much tapping of the memory wires to compile a list

the length of your arm of big men who were not aggressive by nature, couldn’t

hit with any great power, couldn’t take a punch and didn’t actually like the

business of having a scrap.

Hand speed, good footwork, timing, balance and snap are all

essential ingredients of the true puncher and rarely come naturally to men of

excessive bulk. One really doesn’t have to be a scientist or a biologist to

appreciate the reasons why, even though punching technique is about science and

biology. For me, it is a wonderfully intriguing subject to study, one that

requires little more than common sense and logic to comprehend.

So why do so many boxing ‘fans’ fail to take the trouble to learn

or misunderstand the simple equations when they do? Many, I am sure, do little

more than count the knockouts on a fighter’s record in order to measure his

power of punch. Punch stats and the ceaseless stream of other facts and figures

have become as much of a curse as a blessing.

Surfing the various boxing forums, I feel my eyes boggling at

some of the quaint lists I see of the all-time heavyweight punchers. Joe

Frazier, a great sentimental favourite of mine, is a regular people’s choice as

one of the top five hitters, which he never was. Jack Dempsey, Joe Louis, Bob

Fitzsimmons and Max Baer are regularly pushed out of the reckoning by the likes

of Gerry Cooney, Ron Lyle and Bernardo Mercado. Let me add quickly that I do not

mean to demean the latter three gentlemen. Each could wallop and then some.

Cooney, for all the ridiculous hype that surrounded him, had a wrecking ball of

a left hook. I can just think of plenty of other fighters who had a lot more.

Fights

During the course my career as a boxing journalist, which adds up

to some thirty-plus years, I have been to countless fights and watched many

others on film. I love fighters of all weights and styles but accept that the

heavyweights are, and always will be, the ‘wow’ factor of boxing.

That being said, I don’t have to get too heavy in naming the two

men I regard as the most knowledgeable, skilful and effective punchers in the

history of the dreadnought division: Jack Dempsey and Joe Louis.

It is no coincidence that Jack’s best weight was around 190lbs or

that Joe was at his ferocious best between 200-208lbs.

It is a proven fact, like it or not, that fighters of between

190-210lbs generate more measurable power than heavier men.

Dempsey and Louis were natural athletes and possessed natural

killer instinct inside the ropes. Both got excellent leverage on their punches,

moved intelligently and with specific purpose, and had great timing and hand

speed. Bulking up might well have increased their already formidable power, but

their other important advantages would have been blunted. In short, they would

have sacrificed the significant ingredient of athleticism.

Jack Dempsey cut his teeth on knocking out far bigger men. From

the tender age of sixteen, Jack’s famously large and mighty fists were smashing

through the toughs of the mining camps, saloon bars and hobo jungles. The

bronzed and muscled youngster who would become the Manassa Mauler consistently

astounded colleagues and onlookers with his savagery and natural punching power.

Not for nothing was Jack known as the man killer.

I have discussed Dempsey’s many attributes in recent articles, so

let me now come in praise of Joe Louis. With an irresistible combination of

speed, timing and explosive power, Joe would prove that he was no less an

indiscriminate destroyer. Indeed, he shared Dempsey’s relish for hunting bigger

game. The only question to be answered was how Louis would choose to chop and

grill it.

Boxing correspondents in Joe’s time were true boxing writers who

loved the sport and understood its many shades and hues. Reams were written on

style and technique, talent and attitude, by worldly lovers of the game who took

the trouble to talk at length to the deep pool of fighters, managers and

trainers. Bob Davis was a columnist for the New York Sun who saw all the

heavyweight champions from the time of Jim Corbett. Right from the start, Davis

saw something special in Joe Louis. “When he hits, something just has to go,”

Davis explained, noting the slight sway and lift of Joe’s legs as he moved into

an opponent and started to punch. “Louis has everything – power, weight,

marvellous co-ordination and the slash of a rapier in either fist. I watched him

fight and watched him train. The kick in his blow is something terrific, for he

gets everything in his legs and body into it, all swinging in perfect rhythm as

he drives the fist for a vulnerable point.”

New Jersey sports editor Al DelGreco was another fan of the Brown

Bomber. “I think that Joe Louis was the greatest heavyweight of all time because

he was the greatest offensive leather-pusher I ever saw since 1925 when I first

went to fights. He batted out rivals with such swiftness that writers at the

ringside couldn’t pick out the finishing blow and by which hand it had been

delivered. He had a defensive weakness, true, but when he was in his prime he

overcame it with his offensive ferocity.”

Henry Cooper, no mean left hooker during his long reign as

British champion, has long admired Louis. “When I watch his old films, it is his

style that I so like. It was sheer economy of movement as he shuffled round,

always keeping just out of range with the left going jab, jab, jab until he

could unleash that fearsome right that put so many opponents away.”

Columnist Jim Murray loved to write about Joe and did so

frequently. Murray once described the Bomber as “…two hundred pounds of tawny

fury, the hands so fast they were a blur on cameras that would stop milliseconds

of action.”

There was certainly no doubt in Murray’s mind as to how hard

Louis could punch. “Louis hit Braddock so hard, the sweat and water from his

hair sprayed as far as Row 6. He knocked Paolino Uzcudun’s gold teeth in so many

directions, the ring looked as if somebody had stepped on a railroad watch.”

After the brutal dismantling of Uzcudun, the inimitable fight

manager Joe Jacobs memorably remarked, “A guy who can break gold with a punch

shouldn’t be licensed.”

Jack Blackburn

Joe Louis was highly fortunate, of course, in having that

wonderful, battle-scarred sage Jack ‘Chappie’ Blackburn as his trainer. But

while Jack’s immense influence on Louis cannot be sufficiently praised, nor can

Joe’s natural aptitude ever be underestimated. Let us remember that fighters can

only be taught how to think up to a certain point, whatever their degree of

talent. Thereafter, instinct must kick in and take over.

Louis was a great thinker and an accomplished planner who could

always vary his strategy when required. Jack Blackburn drilled him, just as Jack

Grout drilled Jack Nicklaus on the golf range, but the cleverest form of

indoctrination still requires an exceptional and versatile talent to start the

engine and make it purr to its optimum capability.

Joe Louis was as much of a boxer as he was a puncher, something

that cannot be said of too many heavyweight champions. When some critics accused

the young Louis of being a ‘dumb fighter’, Jack Blackburn gave a little smile

and responded, “There are a lot of fighters smarter than Joe, but that don’t

mean anything. Lots of times, smartness and meanness don’t mix and you gotta

have the means to be a great fighter.”

‘Quick like’ was Jack’s favourite little way of describing Louis.

Blackburn

would have known, for he wasn’t too shabby a fighter himself in his day. Sadly

for Jack, he toiled as a lightweight in the less enlightened age of boxing when

a legion of talented black fighters never got their just rewards. For all that,

Damon Runyon rated Blackburn as one of the five greatest boxers he saw. Like

Louis, Blackburn could box and fight. Unlike Joe, Jack was also partial to a

good old scrap beyond the confines of the roped square, picking up plenty of

facial signatures for his troubles. He was once memorably described as ‘an

animated razor scar’.

Damon Runyon wrote of him thus: “Jack Blackburn stood upright and

somewhat flat-footed in his boxing prime. He carried his hands up, each always

in exact position for the delivery of a blow His posture was the acme of boxing

grace. When he moved his feet, it was for a definite purpose. He made a study of

the position of the feet with reference to boxing, and when he advanced or

withdrew one foot or the other, it was with all the calculation of a man playing

a game of checkers.”

Blackburn,

in Runyon’s view, was not as nimble on his feet as Benny Leonard, but Jack had

the superior hand speed. “Benny’s hands were not as fast as Blackburn’s, nor

were those of any boxer of my observation save one. That is Joe Louis, to whom

Blackburn passed on his speed of hands. Louis is slow of foot movement but he is

one of the fastest punchers that ever lived.”

If Blackburn had a key word in his early coaching of Joe Louis,

it was ‘balance’. Get your balance right, he told the Bomber, and all the other

pieces of the jigsaw will click into place. “Chappie had drilled me so much on

hitting and balance,” Joe once said, “that they were the main things I thought

about. I wasn’t worried so much about the hitting. But getting my balance right

was my main problem. As Blackburn said, ‘When you’re hitting right, you’re never

off balance’.”

Blackburn

instilled much of his own feinting and general boxing ability into Louis during

the endless hours they laboured in the gym. Jack regarded the Old Master, Joe

Gans, as the perfect template, teaching Louis how to advance intelligently on an

opponent and never allow the other man to set the pace. The objective was to

make the opponent feel anxious, keep him ever guessing and never allow him

respite.

By the time all the seeds bore fruit, Joe Louis was as near a

perfect fighting machine as there could be, prompting Nat Fleischer to describe

him as “…a pugilistic symphony with a tempo geared to bring him across the ring

with all the grace of a gazelle and the cold fury of an enraged mountain lion.

He combined excellent harmony of movement with crushing power stored in each

hand.”

In short, here was a very special heavyweight who could knock out

any man of any size – and did.

Buddy Baer

Buddy Baer stood 6’ 6 ½’’ tall and weighed 237 1/2lbs when he

stepped into the ring to challenge Louis for the heavyweight title at Griffith

Park in Washington on May 23, 1941. Baer was four-and-a-half inches taller than

the Bomber and nearly 36lbs heavier.

Big Buddy was also a lot more serious about his profession than

his famous brother, Max. Buddy could box well, hit ferociously and had scored 45

knockout in his 49 wins, against five defeats and a no-decision against Lee

Savold.

Baer had got his shot at the title with a seventh round stoppage

of Tony Galento and had also notched wins over Nathan Mann and fellow giant, Abe

Simon.

Buddy was rough, tough and durable, and I would accord him an

excellent chance of winning a portion of today’s sadly fractured heavyweight

championship. When Louis viciously knocked him to the canvas in the sixth round

for the third and final time, reporter Sid Feder wrote, “Buddy went down as

though one of Washington’s baseball Senators had bounced a ball bat off his

head.”

Baer tried his utmost against Joe in a thrilling contest with a

controversial finish. But watch the film of that fight carefully when you get

the chance and study the Bomber’s punching technique. It is a thing of beauty in

its perfect timing and correctness. For all of Buddy’s bravery and the fact that

he never stops punching back, he appears to disintegrate piece by piece as the

unerringly accurate punishment finally registers and dynamites the last of his

resistance.

Let the point be made that Joe was not decimating a crude and

lumbering opponent with little idea of the mechanics of the game. Buddy Baer

moved very well for a big fellow and sensibly protected his chin with his left

shoulder. He punched hard, was fearless in attack and wasn’t hindered by the

ponderous footwork that betrays so many giants. Nor was he at all inhibited by

the big occasion or the mighty task of trying to topple a boxing legend.

Baer traded confidently with Louis from the opening bell and

didn’t back off when Joe spun him with a hard right to the head. It was quickly

apparent that Baer’s chin was up to the task as Louis cracked him with another

big right and a following left hook to the jaw. Buddy punched back and worked

the champion’s body when they clinched. Towards the end of the round, the big

man got his big chance. The Griffith Park crowd roared as a left hook from close

range found the mark and knocked Louis through the ropes. The champion clambered

back into the ring and fired back as Baer rushed him and tried to capitalise on

his golden opportunity. The action was halted when both fighters thought they

heard the bell and headed for their corners. Referee Arthur Donovan pointed out

the mistake and motioned them to continue, but Baer’s chance had gone and now

Joe Louis was more dangerous than ever. Indignity had been added to his already

formidable arsenal of weapons

The fight continued to be exciting and competitive through the

following rounds, but always there was the feeling that Joe was laying the more

solid and impressive foundations. The speed and timing of his punching continues

to floor the viewer all these years later. Whether punching short or long, Louis

threaded his blows through the tightest angles with marvellous precision. His

preparatory work could be alternately quiet and explosive: the constant jabbing

that never quite looked as damaging as it was, the short hooks to body and head

whose speed could make them look oddly lazy in the way of a spinning wheel, the

flashing right crosses to chin and jaw whose thuds carried above the noise of

the biggest crowds.

Baer needed all of his fighting spirit in the second round as Joe

went to work with that quiet terror that set him apart. Baer rushed Louis and

went to the body, then switched upstairs and connected with a left and a right

to the head. Joe shot a left-right combination to the jaw and staggered Buddy.

Louis then rifled home a series of hard and controlled shots that clearly hurt

Baer. Yet the big challenger showed commendable courage and durability in

continuing to chase Joe and fire back. At one point Buddy was struck by three

smashing rights in succession, yet kept coming.

The crowd loved the action in what one reporter would call ‘a

whale of a fight’. Joe was winning the rounds with the superior quality of his

work, but Baer was a delicious loose cannon who never stopped threatening to

upset the apple cart. The action slowed in the third round, but Buddy enjoyed

some early success in the fourth when he raised a small mouse under Joe’s eye.

Baer was still trying to slow Louis by attacking his body, but the challenger

had to take some jolting blows for every small success he enjoyed.

The writing on the wall began to appear in the fifth round. After

taking a hard left hook, Baer bulled Louis into a corner and opened a cut over

the Bomber’s left eye with a hard right. The challenger would win the round with

his greater pressure, but more significant was the feeling that Louis was moving

up to that higher level that only great champions inhabit. Knowing that more

urgent measures were called for, Joe finished the session with a two-fisted

assault that was a portent of things to come.

The conclusive sixth round provided chilling evidence of how

quickly Louis could pounce and kill off a lively and dangerous foe. It was

fitting that Joe had been compared to a mountain lion, for one thought of that

stealthy predator and its famous bite to the neck that so suddenly terminates a

tussle.

Things still looked pretty rosy for Buddy as he opened the stanza

with a left hook to the head. Louis replied by firing three lefts to the body

and slamming a right to the jaw. Back came Baer, game as ever, still looking to

repeat his sensational success of the opening round. Buddy was still hooking and

hustling when Joe manoeuvred him into the trap and belted him with a hard left

and two solid rights against the ropes. Having worked so hard to keep the fight

at close quarters, Baer was suddenly lost at long range as Joe at last had the

room to tee off in earnest. Louis was firing almost at will and there was

nothing for Buddy to grab and hold on to.

Despite the severity of the beating, Baer still found the heart

and resolve to punch back, but then a right from Joe finally unhinged the big

man and felled him for a six count. One of boxing history’s greatest finishers

was now in his element. Another cracking right sent Baer crashing onto his back

for the second knockdown, and this time Buddy only beat the count by a whisker.

The third knockdown was the true masterpiece, as Joe bowled Baer

over with a perfectly timed, whiplash right of terrific force. This was the

punch that enraged Buddy’s manager, Ancil Hoffman, who claimed that the hammer

blow was delivered after the bell. Referee Arthur Donovan ruled that the punch

was right on the bell and therefore legal. However, ringside reporters noticed

that Arthur had turned away from the fighters and was heading to a neutral

corner when Louis dropped the final bomb.

Hoffman refused to let Baer out for the seventh round and the

challenger was disqualified.

Buddy longed for the chance to put the record straight and prove

that he could take Joe Louis. Baer got that chance at Madison Square Garden in

January 1942. Louis knocked him out in one round.

Abe Simon

Before 18,220 fans at Madison Square Garden on March 27, 1942,

big Abe Simon stepped into the ring for the final fight of his career. Scaling

255 1/4lbs, he was a massive, bear of a man who had once used his considerable

size and muscle on the gridiron. Abe outweighed Joe Louis by nearly 48 pounds,

but already knew the dangers of duelling with the Brown Bomber. Just a year

before at the Olympia Stadium in Detroit, Joe had decked Simon four times and

stopped him in thirteen rounds.

Coming back for seconds was never a good idea against the prime

Louis. But Abe had heart, pluck and a big punch and everyone knew that anything

could happen in heavyweight boxing. Simon had knocked out Jersey Joe Walcott in

six rounds, beaten Roscoe Toles and drawn with Turkey Thompson. Abe had also

waged a thrilling battle of the giants with Buddy Baer, in which he had beaten

Buddy severely in the opening round before being stopped in the third.

Simon had a wingspan of 82 ¾ inches and Louis had to get inside

it. It didn’t take the champion too long. Abe fought a gutsy battle, recovering

well after a second round knockdown to land some heavy punches and enjoy some

success at tying Joe up and nullifying his great power.

Louis, by his own later admission, rushed his work in the first

three rounds and had to be told to calm down and slow the pace by handler Mannie

Seamon.

The simple ploy worked. Jack Blackburn was ailing in hospital

with pneumonia that night, but Joe didn’t disappoint his great mentor. He went

big game hunting in the fifth round and set the traps with his usual skill. A

cracking left hook forced Simon to clutch for safety and then the storm raged.

Joe opened a cut under Abe’s right eye and unleashed a ten-punch volley that had

the giant from Long Island softening by the second. Simon, brave to the end,

continued to march forward and plug away, but then a pair of thunderous right

crosses dropped him in his own corner. The bell came to his rescue but only

bought him time and pain that he didn’t need.

Louis finished the fight quickly in the sixth round, sending Abe

down and out with a final left-right blast. Perhaps Joe had been riled after

first snapping Simon to attention with a quick-fire combination in the second

round. Big Abe had laughed at him.

That was a silly thing to do to Joe Louis. It still is.

Especially when the talk turns to big boys being the best.

> The Mike Casey Archives

<

|