The Perfect Execution:

Joe’s KO Of Walcott One Of Greatest Ever

By Mike Casey

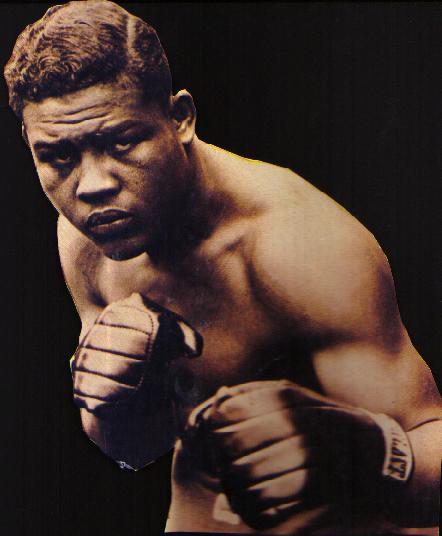

Joe Louis

was an avid golfer for most of his life, even though that gentlest of games hit

him harder in the wallet than any opponent ever hit him on the chin. So let us

kick off with a quick golfing tale, which, I promise you, bears great relevance

to our main story.

In 1979,

to the amazement of the golfing fraternity, the great Jack Nicklaus failed to

win a tournament for the first time since turning professional in 1962. For

seventeen monotonously punishing seasons, the Golden Bear had caned a succession

of challengers. Then nothing. The genie had seemingly escaped from Jack’s

bottle. The drought persisted into the summer of 1980, and then the Bear

suddenly roared again. Out of nowhere, he won his fourth US Open title.

What had

kicked him back into life? Well, a certain mischievous reporter had written a

scathing assessment, quite possibly tongue in cheek, of Jack Nicklaus at the age

of 40. The impudent scribe described Jack as “… done, finished, washed up….”

Nicklaus

pinned those words to his refrigerator door and kept looking at them before

going out and winning one of golf’s greatest prizes against all expectations.

Some

thirty-three years earlier, on the morning of December 6, 1947, Joe Louis had

been faced with a similar challenge. The previous night at Madison Square Garden

had been a painful experience for Joe. Thirty-three years of age but looking

suddenly much older than his years, he had apparently been deprived of his

wonderful gifts all at once by the temperamental gods.

The lithe

panther that had destroyed a generation of challengers had lost its bite and was

limping. The spring and the speed had gone out of Joe Louis and the quick-fire

guns at the end of his arms were no longer firing. Jersey Joe Walcott, arrogant

and smiling, feinting and side-stepping like a ballroom dandy, had outpointed

the great Brown Bomber in the eyes of most and won the heavyweight championship

that had been locked in Jolting Joe’s grasp for more than ten years. Louis,

perhaps sentimentally, was awarded a split decision, but his disgust at his

performance was evident as his handlers were forced to prevent him from leaving

the ring before the verdict was announced.

It had to

be the end, surely. Joe would get Walcott in the return, insisted the faithful.

Joe always got ‘em in the return. Nobody made the Brown Bomber look bad twice.

But how could Louis come back from this? Even Joe couldn’t beat Father Time, and

the old white-haired fellow had finally nailed him.

“I won but

I was disgusted with myself,” Louis said. “It was a bad fight. I always said I

wasn’t the man I was at twenty-three.”

Referring

to the two knockdowns he had suffered, Joe added: “The reason I stepped into

rights is that I was going in. If I’d stayed back, it would have been a lousy

fight. He’s not the smartest fighter nor the trickiest I faced.

“I got hit

hard a few times. I thought he had five or six good rounds. I won’t be satisfied

till I fight him again. History generally does repeat. I do better in my second

fights.”

Joe’s

trainer Mannie Seamon also tried to put on a brave face. “I could have made it

look more like a fight, but I told the champ to keep boring in, trying for a

knockout.”

The

Louis-Walcott match wasn’t just a fight. As ever with Louis, it was a major

event that captured the interest of the world. Joe, like Jack Dempsey before

him, transcended boxing to reach out and touch those who normally wouldn’t have

given a hoot about two guys going at each other in a ring. A crowd of 18,194

poured into the Garden on the night of December 5, 1947, fully expecting the

great Louis to add another glorious chapter to his legend. Oh, yes, their Joe

was ageing and his stint in the army had slowed him down and put some premature

years on that famous poker face. But no matter. Walcott would go the way of all

the others.

The

receipts of $216,477 made it a record gate for the Garden and Joe was favoured

at 1 to 10. Even money was being offered on Walcott failing to survive beyond

the fifth round.

Everything

seemed to be in favour of Louis, who was the bigger man by nearly seventeen

pounds at 211 to Walcott’s 194 ˝.

Then it

all started to go wrong, with Walcott setting the tone in a shocking first round

as he fired a hard right to the head that toppled Louis to his knees for a count

of two. Jersey Joe was all movement, a veritable ball of confusion. There was no

definitive pattern to his repertoire of shifts, feints, back-pedalling and

side-stepping. Louis kept pursuing his elusive challenger, but this hunt yielded

nothing but booby traps and ambushes. In the fourth round, another flashing

right from Walcott spilled Louis, and Joe rested on one knee until the count

reached seven. The Brown Bomber’s left eye was already swelling and the buzzing

crowd began to contemplate the unthinkable. Was this really it? Was the Bomber’s

great reign coming to an end?

Like a man

who taps his chest and discovers to his horror that his wallet is no longer in

its safe and familiar cache, Louis kept fumbling for his old firepower. It

wasn’t there. The steam had gone out of that ramrod left jab and the famous,

shattering right cross. He was constantly confused by Walcott’s herky-jerky

style, which one reporter compared to ‘a backfield shift in football’. Jersey

Joe would often take three steps backwards or three steps sideways and then fire

a left hook or right cross with great speed.

Louis kept

pushing forward, trying to turn the tide with one magical combination of

punches, but an incident in the ninth round summed up his plight when he

cornered Walcott and couldn’t pull the trigger.

The noise

of the crowd was deafening as the fight drew to a close, most expecting to see a

new champion crowned. Louis’ left eye was nearly shut and blood leaked from his

nose as he made his vain attempt to duck through the ropes at the final bell and

spare himself further agony.

Then he

was saved. Referee Ruby Goldstein scored the fight 7-6-2 for Walcott, but was

outweighed by judges Frank Forbes and Marty Monroe, who saw it 8-6-1 and 9-6 for

Louis respectively. The aggregate points of the scorecards showed Walcott

winning by 37 points to 32, but aggregate points didn’t cut any ice in New York

in those days.

When

announcer Harry Balogh declared the decision, he took the Bomber’s glove and

tried to raise his arm. Louis resisted. He was an honest professional to the

core and would have no truck with shallow celebrations.

Walcott’s

trainer Dan Florio was angry and animated in the challenger’s corner before

defiantly leading Jersey Joe to centre ring and raising his arm.

Now let us

carefully consider Walcott’s comments, which tell us quite a bit about him. “I

was robbed tonight without a pistol. He’s a great fighter. He had to be to take

the punches he did tonight. I can beat him every time. I can trick him into any

move I want to make. I’d like to fight him again tomorrow or any time. I was so

far ahead, they (my handlers) told me to slow up in the last three rounds.”

We will

revisit Jersey Joe’s cocky streak at a later point.

Greatness

It was

three o’clock in the morning during a warm August in old New York in 1911. Eager

young reporters Nat Fleischer and Dan Daniel heard police whistles and ran to a

building where a couple of patrolmen were chasing a fleeing suspect. It was one

of many adventures that Fleischer and Daniel would share during a friendship

that endured for many years. Both were men of forceful opinions who often saw

eye to eye.

However,

regarding the question of the greatest heavyweight in history, Nat and Dan went

their separate ways. To the day of his death in 1972, Fleischer, founder and

editor of The Ring magazine, insisted the all-time king was Jack Johnson.

Here is

Dan Daniel’s opinion: “The Joe Louis who knocked out Max Schmeling in one round,

the Louis who took the title from Jimmy Braddock, the Louis who went up and down

the line taking them all on, the Louis who dodged nobody and was eager to meet

everybody, was the greatest heavyweight of all time.

“The Louis

who was threatened on points by Billy Conn and then stopped him, the Louis whose

second effort against Jersey Joe Walcott was devastating, the Louis who could

box, who could hit, who could pile up points or end a fight with one punch -

that man had no equal among the heavies I have seen.”

Fleischer’s son-in-law, Nat Loubet, who would take over the reins of The Ring,

was similarly swayed by Louis: “Although I saw Dempsey, Tunney and Max Baer in

action during my childhood, my first connection with boxing as a profession

began during the reign of Joe Louis. I have seen motion pictures of championship

bouts previous to this but I still vote for Louis as the best of the heavyweight

champs.

“Joe

defended his title twenty-five times, more than any other title holder, barred

no one, faced all contenders, possessed a dynamite-loaded left hand with

possibly the best jab of them all.

“As a

fighting machine, he was not fabricated. He was born to his profession. A

natural with all the instinct of a great fighter and superb gentleman.”

Writer Lew

Eskin said of the Brown Bomber in 1962: “My days on the boxing beat go back only

to the rise of Joe Louis to fistic fame I first saw him when he was somewhat

past his peak, at the time when he engaged Billy Conn in their second fight.

From what I saw then and what I have seen since Joe’s retirement, I place him as

the number one heavyweight, at least of the last two decades.

“From what

I have seen in person and the movies of old-time contests, I cannot concede that

even the old-timers were greater than the Brown Bomber. He had everything that

goes to place a heavyweight in the class of greatness.”

Despite

the frightening number of years that have slipped past since the Bomber left the

stage, many of today’s historians are no less impressed. Monte Cox says of

Louis: “He was quite possibly the greatest boxer-puncher of all time, certainly

the best among the heavyweights. Louis’ style was to put subtle pressure on his

opponents, cutting the ring, forcing them back and then taking precise steps

backwards to lead his opponents into his terrifying counter punches.

“In his

prime, Louis threw perfect jabs, triple left hooks and short jolting right hands

that landed literally with bone-crushing power and laser accuracy. The Brown

Bomber also threw some of the most magnificent combinations ever seen.

“Not only

was Louis a feared puncher, but he was a great boxer who had learned how to set

up his opponents and catch them coming in as a true master of the

counter-punching art.”

Tracy

Callis adds: “Many experts consider Louis to be the greatest counter puncher

among the heavyweights. When the slightest opportunity presented itself, the

right-left exploded.

“His

offensive capability was most likely unequalled in the ring. He performed at

optimum efficiency, with little wasted motion. His style was that of a stand-up

boxer with quick reflexes. He carried his guard moderately low. His defence

consisted of a superb offence.”

Some years

ago, reporter Sid Feder simplified the appeal and greatness of Joe Louis in

describing Joe as “… a fellow of first principles, a fellow of fundamentals.”

Wrote

Feder: “There has never been anything intricate about the mechanism of Joe

Louis. As a fighter, the heavyweight champion has gone into the ring with these

rather important fundamentals: a punch in either fist. Condition and fitness.

His full share of courage. Respect for the other fighter but belief in himself.

No thought of an alibi or an advance excuse. No thought of a foul punch. The

ring has known no finer sportsman.”

Purity

Some

people have described Joe Louis as robotic and predictable. I have never been

too hard on those people. I can see where they are coming from. For the most

part, Joe was a flat-footed fighter, a shuffler, very purposeful and deliberate

in his approach. Perhaps that is why his opponents stumbled and fell. They

watched the slow shuffle and missed the lightning quick fists and the clever

mind.

Scientists

and sci-fi enthusiasts tell us that man will only survive the torrid conditions

of future worlds by evolving into a highly sophisticated android with a human

brain. Joe Louis might just have been boxing’s prototype of this irresistible

combination.

Lord, how

fast he could punch. Damon Runyon never saw anyone faster. But it is the

correctness and superb timing of Joe’s punches that never ceases to fascinate

this writer. There was a purity about Joe’s hitting that I haven’t seen since.

At short range especially, his left hooks and chopping rights were devastating.

Ponder all those films you’ve seen of Louis and consider, for one thing, the

terrible mess he made of opponents’ faces.

Most

importantly of all, perhaps, Joe Louis was a genuine two-fisted knockout

puncher, and those birds are very rare. He could take you out with one shot or

any number of shots you cared to take.

He wrecked

Johnny Paychek with a single right cross. He did likewise to Jim Braddock after

clearing the path by cleverly shoving Jim’s left out of the way. Braddock, never

an excitable man of purple prose, would later compare the Louis jab to an

electric light bulb being rammed into the face and then shattered.

Even

before Joe’s shocking loss to Max Schmeling, Damon Runyon was convinced that the

Bomber belonged in the highest echelon. Writing about Louis in 1936, Damon said:

“He is without doubt one of the greatest punchers that ever lived, but why?

Kindly bear in mind that we don’t say Louis is THE greatest puncher of all time,

merely one of the greatest. We have seen a lot of fellows, who, pound for pound,

could punch just as hard, but in an entirely different manner.

“However,

we never saw but two or three who could punch with both hands as Louis can,

which happens to be part of the secret of his punching power.

“He can

tag an opponent with a left hook, for instance, and finish him with a right

hand, whereas a strictly one-hand puncher has to keep repeating with that

hand.”

Runyon

rated Louis close to Stanley Ketchel as a two-fisted hitter and also cited Sam

Langford as a master of that art. Of Stanley, the great Michigan Assassin,

Runyon wrote: “Now Ketchel had a curious style as his own. He fought from a

widespread stance. He was a slam-bang type of fighter, driving in with desperate

courage, and he had a peculiar shift, so that if he fired with one hand and

missed, he could let go with the other hand without losing his balance. Ketchel

didn’t bother much with the fine scientific points of boxing. He just tore in

and let both hands rip.”

Sam

Langford, of course, was a wholly different animal, of whom Runyon wrote: “Sam

at his best was a great puncher with both hands. He was a fine boxer as well as

a puncher, in which Louis resembles him.

“Langford

had a great left hook and he also had a corking right hand. He was death on

other left hookers as a rule. He would knock ‘em bow-legged with a short right

inside a hook.”

The

ability to knock out a man from short range is a wonderful gift, very probably

an innate gift. Historian and film researcher Mike Hunnicut certainly believes

so. Through a process of admirably detailed measurements taken from original

16mm films, Mike has proved that Joe Louis and Jack Dempsey stand alone as the

assassins who could end a fight from the shortest distance. “Of the many films I

have, Louis and Dempsey scored the most knockdowns or knockouts from very close

to two feet or less. Jack’s percentage is about 30, and Joe’s 20. None of the

others even get close to those percentages. The set-up shots by Louis and

Dempsey were sometimes even shorter – classic six-inch punches. These were the

two aces who could punch short or long and get you from any distance.

“There

have been many other great punchers of course. Marciano got tremendous leverage

on his shots, but only Louis and Dempsey could knock out the toughest men with a

blow from two feet or less.”

The return

The second

fight between Joe Louis and Jersey Joe Walcott, originally slated for June 23,

1948 at Yankee Stadium, was twice postponed because of rain and reset for June

25.

Although

there was a big swing of public opinion in favour of Walcott as fight time

approached, the general feeling of those in the know was that Louis would

produce one final burst of the old magic.

Jersey

Joe’s runaway tactics in the first fight, and his subsequent rants about the

injustice of it all, hadn’t endeared him to many writers.

Alan Ward,

sports editor of the Oakland Tribune, had some strong feelings on the subject:

“I like Joe Louis to cool Jersey Joe Walcott within nine rounds, but the champ

may have to climb off the floor to do it. As far as the first Louis-Walcott

fight was concerned, I’ll repeat what I said then. Walcott may have won that

particular bout, but he didn’t win the title.

“Jersey

Joe may have had a small technical edge, but he showed little that would

establish him as worthy to follow the likes of Joe Louis, Gene Tunney, Jack

Dempsey or even Jim Braddock.

“True

champions don’t run to protect a lead and Jersey Joe showed more rabbit than I

care to observe in a top flight fighter in several rounds of the December

fight.”

Among

others who predicted a Louis victory were Dave Egan of the Boston Record, Lawton

Carver of the International News Service, and Joe Vella, the manager of Gus

Lesnevich.

Former

champion Jim Braddock was also riding with the Brown Bomber. “Louis will win

this time the way he always does. He’s a great fighter and never makes the same

mistake twice.”

Just two

years before, Billy Conn had discovered that even an old and rusty Joe Louis

could learn new tricks and fashion new game plans. Billy, the hero of 1941 after

his epic stand against Joe, could not hoodwink the creaking but still dangerous

Brown Bomber of 1946.

Here is

writer Oscar Fraley’s humorous account of that second engagement: “Joe Louis,

still heavyweight champion of the world, abandoned his poker face Thursday and

actually grinned because he called his shots – and the rest of the boxing world

didn’t.

“It had

called him ‘too old’ and it had called him ‘too slow’. And it said that the

younger Billy Conn might lift boxing’s biggest crown off from over that famed

poker face.

“Thursday

the poker face is gone – but the crown still is there over an unfamiliar grin.

“The tawny

Brown Bomber proved after a five-year layoff that he was none of those things

but still the deadliest puncher in the ring. Three sharp, conclusive blows had

made Billy The Kid a retired citizen of Pittsburgh, Pa.”

For all

the great anticipation, for all the great expectation of Joe Louis reclaiming

the glory days of his prime, a familiar story took shape at Yankee Stadium, a

depressing story for fans of the Bomber. Knocked down briefly in the third

round, Louis appeared once again to be chasing a jigging, side-stepping ghost.

Joe trailed on points after ten rounds and the crowd was booing the lack of

meaty action.

Then that

cocky streak in Walcott showed itself. It did so disastrously. Breaking into a

little shuffle and strut, he decided to trade punches with Louis. Jersey Joe had

been strictly advised not to do this. A thunderous right to the temple severed

all movement in Walcott, rooting him to the floor and teeing him up for one of

the greatest combinations ever thrown.

The

ripping punches that followed, short and perfectly sweet, stretched Jersey Joe

flat on the canvas. He clambered to his knees, nearly made it to his feet at the

count of nine, but fell back down to take the count.

For this

writer, that wonderful and immaculately timed salvo continues to represent

economical power punching at its most sublime and thrilling. I have yet to see

it eclipsed for its strange beauty and disciplined savagery.

Monte Cox

places that great knockout into its overall perspective: “World War II robbed

Joe Louis of his gifts. Four years of inactivity without serious competition

seriously diminished his skills. Joe’s sense of judgement, distance and timing

marvelled the boxing world in his prime. Now an old, slowed, balding Louis had

lost the reflexes that had made him so special at his best. His last great

effort was his rematch against Jersey Joe Walcott.

“This was

a must-win for Louis, his reputation as an all-time great was on the line. Louis

was foiled by a sharper Walcott, whose moves, jukes and multiple feints could

bewilder almost anyone. Louis simply had trouble finding the range. In the

eleventh round, after an exchange, Louis stepped back. Walcott, believing he

might have Louis in a peck of trouble, moved in. It was the spider leading the

fly into his trap.

“Walcott

missed a right as Louis moved back and the Bomber caught him with a right hand

that froze him. Now with Walcott momentarily stunned, Louis opened with a flash.

The final devastating combination was Louis’ last flurry of greatness. For a

moment we saw the Joe Louis of old, not an old Joe Louis. Walcott crumbled to

the canvas and was counted out.

“Joe

retired after that fight. He came back but we never saw the real Louis again. He

was still a solid fighter, still had a good jab and was fundamentally sound, but

his once great punching skills were gone. He scored only three knockouts over

the last ten bouts of his career.”

Mike

Hunnicut couldn’t help seeing the funny side of the classic knockout: “It was

another fine example of what happened when a Louis opponent got too cocky. Even

against a shot Louis, the opponent got splattered. Everyone knows that Louis was

perhaps the most effective puncher in heavyweight history. Louis let that

range-finding jab out and then the fight was over when he smashed that right to

the temple.

“It was

almost humorous. To finish things up, he drove home the final shots as if he

were going straight through good old Joe Walcott.

“Think of

how discouraging it must be to fight a Joe Louis. You use all the well trained

leverage you have at your disposal, only to discover that he hits way harder by

a comparative tap.”

Finishing job

Joe Louis

was understandably happy after the fight. “You know, that finishing job I did on

Walcott was one of the best I ever put over,” said the Bomber.

“Somebody

asked me what punch put Walcott on the way out. Who knows? I don’t. I was

throwing them so fast, I couldn’t remember. It doesn’t matter.”

The

dejected Walcott had strong words for referee Frank Fullam. “I thought I had

Louis. Then the referee kept telling me to come out and fight. He didn’t tell

Louis – just me. It got me confused. I changed my style of fighting and this

happened. I only remember that first punch – a right to the head. They say he

hit me some more – I don’t remember.”

This was a

familiar squawk from Jersey Joe. Here is a man, some revisionists would have us

believe, who has been underrated and unappreciated. I don’t think so. I don’t

think history has misjudged Jersey Joe Walcott any more than it has sold short

the greatly gifted but fatally temperamental Jack Sharkey. I don’t believe that

either man was deceiving us. I don’t believe that either possessed a reserve

store of magic that never saw the light of day.

Walcott

got five cracks at the championship in the days when most others got one. He

dropped the ball four times. By his own admission, he eased up in the last three

rounds of the first Louis fight. Why? A challenger should never do that. Jersey

Joe complained that the referee caused him to revise his game plan in the second

match. More fool Walcott for his lack of discipline and commitment. Louis would

have politely acknowledged the referee and then carried on at the same sweet

pace.

Jersey Joe

was still whining five years later in his return go with Rocky Marciano. After

going out like a lamb and missing the ten count by the proverbial street,

Walcott got up and complained with far greater gusto than he had shown during

the brief contest.

He was a

grand ring mechanic at his best, but he had the hot head and cocky streak of

Billy Conn. Billy, at least, could smile at his own folly. A likeable soul, he

was even partial to an amiable chat in the clinches. He spoke to Joe Louis twice

in their return battle.

Recalled

Conn: “In the first round I told him to take it easy – he still had fifteen to

go. Then later, when he had me on the ropes and was swinging, I said, ‘What you

trying to do to an old pal?’”

In all his

playfulness, Billy had forgotten one of Joe’s most stringent rules in life: Pals

don’t count during business hours.

> The Mike Casey Archives

<

|