Touching The Void: The Hawk And The

Schoolboy In Late ‘82

By Mike Casey

I’m

tired of living and scared of dying. So go the famous old words of Ol’ Man

River. It’s funny how people see life and death in different ways. We all have

our fears and our phobias.

During my

long career in journalism, I have had the good fortune to meet many men of

courage from various walks of life, be they boxers, soldiers, firefighters,

policemen or humble nine-to-fivers who never imagined they could be Superman for

a day.

Few have

been tired of living, yet they have been strangely scared of it. They can only

live joyously when life is spiced with danger and the price of failure is

savage.

Understand

that such men do not harbour a death wish. What they need is the challenge and

the adrenaline charge of venturing into the valley of death and daring it to

swallow them up.

We should

not be too harsh on our heroes who fall apart and lose themselves when there are

no more titanic battles to wage. What else does a man do, where else does he go,

once he has touched the void and taken a peek at that mystical halfway house

between the present and hereafter that mortal men only get to see at the moment

of dying?

He can

perform the impossible when he is lost in that magical world. He can beat anyone

or anything. Then the bubble bursts, his theatre of dreams is dismantled and

suddenly he is being eaten away and driven mad by the ticking of a clock in a

lonely house.

Bobby

Chacon knew all about the monotonous ticking of clocks. I suspect that Aaron

Pryor did too. Both were fast and dangerous fighting men, forever barrelling

towards the next target in life at breakneck speed. There is no greater curse

for such warriors than a pregnant pause or an empty space.

In the

early hours of December 11, 1982, the day when he would go out and win the

greatest fight of his career, Bobby Chacon couldn’t sleep. His wristwatch kept

beeping out the time as the hours passed with agonising slowness. Chacon knew

only one way to struggle through the darkness. Focusing on his opponent, the

formidable Rafael ‘Bazooka’ Limon, Bobby kept saying to himself, “I can’t lose,

I can’t lose.”

By this

time, Aaron Pryor’s work was done. A month before, on November 12 at the Orange

Bowl in Miami, the whirlwind of a man they called The Hawk had swooped through

the valley of death and somehow emerged victorious against a living legend in

the great Alexis Arguello.

None of us

could quite believe what we had seen in that fight. It had soared and dipped and

charged along like a violent, rocking rollercoaster, fuelled by courage, heart,

passion and an almost disquieting brand of commitment.

Aaron took

the cheers of the screaming crowd. It was Hawk Time, just as he always liked to

tell us. Did he sleep that night? Had he slept the night before? And what would

such a volcanic and hyperactive man do when there were no more wars to be

fought? Nights can be killers, but days are even longer.

Perpetual

Perpetual

motion is a thrilling and dangerous condition in human beings. Thrilling because

we love to see it and wish we had it. Dangerous because it is finite. A

neighbour of mine in our Kentish haven here recently passed comment on a

tireless woman in our community who charges around the place organising outings,

garden parties, theatre trips, you name it. She is greatly admired and rightly

so. But my neighbour’s take on her kept coming back to me: “It’s almost as if

she’s afraid to stop in case she discovers she has nothing else to do.”

Well,

those of us who know our boxing are all too aware of the personal demons that

came to claim Aaron Pryor and Alexis Arguello after the final bell had sounded.

Reams have been written on how the two titans of the ring were yanked from the

heights to the depths. We call them ‘human interest’ stories in journalism and

your writer tends to steer clear of them. However well intentioned, they still

end up smacking of glorification and sensationalism.

So forgive

me for being sentimental and singin’ in the rain like Gene Kelly. This little

forum has been roped in to include only the glory days of late 1982, when Aaron

Pryor and Bobby Chacon were kings of the hill and monarchs of all they

surveyed.

With

typical melodrama, they left it late and then left us with one heck of a bone to

chew on. Around November time, as every boxing fan will know, we start picking

our fight of the year. We figure that it’s pretty safe to do so, that everyone

has done what they are likely to do.

In 1982,

having pretty much finalised our neat little lists, we got beaned by two of the

most vicious curveballs ever thrown. Pryor overwhelmed Alexis Arguello in the

fourteenth round of an almost impossibly fast-paced and brutal battle. That

clinched it, surely. The fight of the year beyond question. Then Chacon

outlasted Rafael Limon at the Memorial Auditorium in Sacramento in a primitive

and surreal war of attrition that didn’t seem to take place in the real world.

Those who personally witnessed that spectacle reeled uncertainly into the

streets and the parking lots when it was all over, bearing the stunned

expressions of alien captives who had been whisked off to another star system

for a few quick experiments and then tossed straight back.

The fight

of the year? Definitely. Well, definitely maybe.

Pryor and

Chacon just kept punching, just as Ad Wolgast and Battling Nelson had done

decades before, just as Stanley Ketchel and Joe Thomas had done in their

thunderous classic at Colma. Where do such men go at such times? They seem to

stop that ticking clock that they fear and slip into a private heaven where

everything is constant and makes perfect sense.

I remember

vividly how Aaron Pryor charged to the fore with remarkable haste. What a

wonderful breath of fresh air The Hawk was. His progress through the

professional ranks was as fast and as furious as his fists. Suddenly the

ferocious kid from Cincinnati just seemed to be there, knocking at the world

championship door before most of us had managed to peruse his application form.

Twenty-four wins in just under three years, twenty-two knockouts, and he was

ready for the mighty Colombian Antonio Cervantes. Pryor was a living embodiment

of Jack Kerouac’s freefall prose, where full points and commas are regarded as

unnecessary inconveniences. Don’t stop the flow! Keep charging on!

Aaron had

roared out of the amateurs with a 204-1 record and he just kept roaring as he

made the transition to professional in 1976. Only Jose Resto and Johnny

Summerhays managed to take The Hawk the distance on his charge to the

championship.

The great

Antonio ‘Kid Pambele’ Cervantes was a fading but still formidable WBA

junior-welterweight champion when he journeyed to the Riverfront Coliseum in

Cincinnati to defend his championship against Pryor. By the time Cervantes

journeyed home again, his manager Ramiro Machado was saying, “We are finished.

No more fights.”

In fact

Cervantes would have five more fights and win four of them. But he would never

touch championship heights again after being brutally swept asunder by Pryor.

The 5’ 10” Cervantes had seen off eighteen challengers to his crown with his

height and great punching power. As a junior-welterweight, only those classic

boxing masters, Nicolino Locche and Wilfred Benitez, had inconvenienced the

stately Colombian by way of silky skills and finesse. Overpowering Cervantes was

another question entirely and not recommended to fighters of good sense.

Aaron

Pryor, however, could never be truly profiled or bracketed. He was his own

raging storm, blowing every which way and defying classification. He was quite

simply glorious. He took the breath away as the special ones always do. And he

took the fight out of Cervantes inside four rounds.

It all

started well enough for Antonio, who wasn’t accustomed to being batted around

and might have come to believe that it couldn’t happen. He looked his old lithe

and dangerous self in the opening two rounds, hurting Aaron in the first and

then sending him down on one knee in the second. Pryor claimed he slipped but

the official ruling was a knockdown. Not that The Hawk dwelt upon the incident.

He never did pay much attention to adversity in the ring, sweeping it aside like

a troublesome bee.

Pryor’s

endurance matched his fire and fury. His ability to absorb punches with apparent

immunity would be seriously questioned two years later against Arguello. But it

was Aaron’s cyclonic offence that ultimately crushed Cervantes. Like a rabid

version of Henry Armstrong, Pryor would just keep firing.

In the

third round, Aaron cracked home a left hook to open a one-inch gash over

Antonio’s eye, and the old champion was suddenly looking uncertain and

vulnerable. Always a demon at finishing a man in distress, Pryor wasted no time

in going to work in the fourth round, chasing Cervantes into a corner and

letting fly with a barrage of blows. A final right to the head sent Antonio to

his knees and left him clutching the lower ropes. A magnificent champion had

finally been toppled and unceremoniously ripped apart. “I was sad about the

knockout,” Cervantes said. “If I don’t get cut, maybe it would have been mote

interesting.”

Possibly

but unlikely. Pryor was now approaching the raging prime of his life as a

fighter and quickly established himself as a dominant champion in his own right.

The challengers to his throne quickly came and quickly went: Gaetan Hart in six

rounds, Lennox Blackmore in two, Dujuan Johnson in seven, Miguel Montilla in

twelve and Akio Kameda in six.

Then it

was the turn of the mighty Alexis Arguello in the electric atmosphere of Miami’s

Orange Bowl. What a match-up! Most of us sensed that a meeting of Aaron and

Alexis couldn’t fail to be a very special and thrilling spectacle.

What can

one say about the great Arguello by that time in his career? There he stood, the

lanky Nicaraguan known as El Flaco Explosivo (The Explosive Thin Man), with

three titles in three weight divisions already on his ledger and an eye-popping

record of 77 wins in 82 fights, including 62 knockouts. Yet Arguello was much

more than merely a destructive puncher. He was wily, intelligent, a cool master

boxer into the bargain.

He could

outbox his rivals when the occasion demanded or knock them out with a strike of

frightening suddenness. When he tore the WBA featherweight crown from the head

of Ruben Olivares in 1974, the big bomb came late in the day and stunned the

Inglewood Forum crowd into momentary silence. A single, cracking left hook to

the jaw unhinged Olivares, just when it seemed that the Mexican ace had solved

the Arguello puzzle and found the path to victory. The punch sent Ruben’s

mouthpiece flying and dropped him like a man who had been hit by a car. Bravely

he got to his feet, but he was quickly knocked out by Arguello’s concluding

combination.

However,

it was as a junior lightweight that Alexis found his true domain, winning the

WBC title from Alfredo Escalera and seeing off eight challengers before making

an equally smooth transition to the lightweight division and taking the WBC

bauble on a commanding decision from the hardy Scottish southpaw, Jim Watt.

Arguello

was moving up through the divisions with all the smooth assurance of a finely

tuned Ferrari and was no less confident of his ability to dethrone Aaron Pryor.

There was an elegant and almost royal air about Alexis. He was a natural born

killer of the ring, yet his class and sportsmanship never cast him in the role

of the marauding villain. Arguello’s idea of the ultimate fight was an

ever-shifting chess game, not a slam-bang affair of little depth or

intelligence.

His shrewd

old trainer Eddie Futch saw many comparisons between Arguello and a certain

other former pupil: Joe Louis. Talking to reporters in the run-up to the Pryor

fight, old Eddie said of Alexis: “He reminds me a lot of Joe Louis in and out of

the ring. In the ring, he keeps the pressure on you with that hard, straight

left hand. Out of the ring, he is the same quiet gentleman Joe Louis was.”

Then

Alexis met Aaron in a chess game that combined skill, nerve and an oddly poetic

form of brutality. Arguello was the grand master looking to put the young

pretender in his place. Pryor was the charging cavalier looking to clear the

board as soon as he could.

Private War

One

wondered how they managed to extend their private war to the fourteenth round.

Even people in the crowd of 23,800 were physically and emotionally drained at

the finish. They had seen everything that constitutes a wonderful and

competitive prizefight: skill, courage, passion, perseverance and incredible

physical and mental strength. They had seen hard hitting, durability, defiance

and glorious rallies in the face of adversity.

Pryor, the

shorter man by three inches at 5’ 6 ½” started fast, rattling Arguello with

rapid-fire combinations to the head and showing great hand speed. Alexis

displayed tremendous coolness under fire and great resilience in weathering

these storms and firing back with his own formidable artillery. Pryor exerted

great pressure through the first five rounds, but thereafter began to mix his

slugging with some intelligent boxing. Arguello, a marvellous counter puncher,

always looked the more precise and damaging hitter, but could not match Aaron

for volume.

Nevertheless, the balance of power constantly tipped back and forth as each kept

the other in check. The eleventh round was a rocky session for Aaron, as he

seemed to wobble and lose his way momentarily after taking a big right to the

head and a debilitating left to the stomach. Yet this was one exceptional man

that the lethal Arguello simply couldn’t put in the ground. Alexis must have

wondered if a falling chunk of masonry would have had any greater effect on

Pryor.

Aaron kept

coming and kept rifling home punches. He stepped up the pace again in the

twelfth round and maintained his forward march in the thirteenth, despite taking

another cracking right from Arguello. In the ferocious and fateful fourteenth

round, The Hawk finally broke the great man from Nicaragua. No longer could

Alexis ward off the runaway train as he suddenly wilted from a heavy right to

the jaw and a follow-up left. As he staggered back into the ropes, Aaron leapt

on him and fired off a succession of fast and hard blows to the head. Some

counted twenty-three in all. South African referee Stanley Christodoulou jumped

between the fighters and called off one of the great modern wars of attrition.

Arguello

fell slowly to the canvas and lay there with his nose broken and blood running

from his left eye. It was some minutes before he was able to leave the ring to a

thunderous ovation.

Well, as

our fellow historians will know, the big fight was followed by the big

controversy. Had Pryor been flying through that titanic battle on something more

than pure adrenaline? Arguello’s agent, Bill Miller, certainly thought so,

claiming that no post-fight urine samples were taken from Pryor. That didn’t sit

at all right with Miller, who added that Aaron’s trainer, Panama Lewis, was

heard on cable TV asking for a bottle with a special mixture. Pryor’s cornermen

were also seen breaking capsules under their fighter’s nose during the contest.

Arguello,

ever the gentleman, expressed surprise at is opponent’s ability to take the

hardest punches with little visible effect, but didn’t want to press the matter.

“I don’t know what happened,” Alexis said. “I don’t want this thing to go too

far. I was beaten by a great champion. There is no doubt in my mind. I don’t

want to question his ability or honesty.”

Panama

Lewis, for his part, claimed the bottle with the ‘special mixture’ consisted of

Perrier and tap water. There was a disturbing sequel to the story on June 16th

of the following year, which may or may not tell us something. Nashville

welterweight Billy Collins Jnr, whose father had been a top ten 147-pounder in

the sixties, was savagely beaten by Lewis’ charge, Luis Resto. Young Billy’s

eyes were pounded shut and his nose and mouth were horribly gashed and bashed.

It was

subsequently discovered that Resto’s gloves had been cut and half the padding

removed. Lewis and Resto were banned from boxing for life and Resto served a

prison term for assault and other related charges.

Billy

Collins Jnr never did recover from the incident. Plagued by bouts of depression

and drinking, he died nine months later at the age of twenty-two.

The kid From The San

Fernando Valley

It was

somehow typically perverse of Bobby Chacon that he should come along as a

grizzled and gnarled veteran of thirty-one and show Mr Pryor and Mr Arguello

what a REAL fight was.

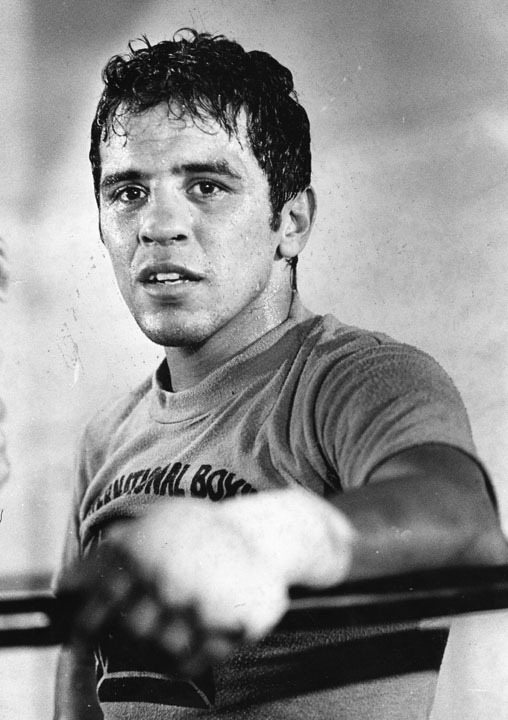

Even at

that age, even after a tumultuous, helter-skelter life of joy and despair, we

were still calling Chacon The Schoolboy. We were still thinking of him as the

pugnacious young kid from the San Fernando Valley.

I do not

intend to recount Bobby life story here, since I, along with many others, have

already done so. Well documented are Chacon’s many trials and tribulations and

his need to fuel his fire by constantly dancing with the Devil.

Worth

remembering, however, is just how highly regarded Chacon was in the twinkle-eyed

days of his youth, long before he walked through fire and came back to bring his

career to a roaring climax at a time in his life when many of us had thought he

might already be dead and gone.

After just

two professional fights, Chacon was already being noticed by reporters and

hailed as Southern California’s best prospect since Mando Ramos. Frankie

Goodman, boxing columnist of the Van Nuys News, said: “Bobby Chacon is the

Valley’s most sensational fighter in a long time.”

Bobby was

living in Sylmar at that time and training at the Main Street gym and at the

downtown Elk’s Club Gym, where he was crossing swords with some illustrious

‘sparring partners’. Among those who showed the kid some tricks of the trade

were Ruben Navarro, Danny Lopez, Arturo (Turi) Pineda, Fernando Cabanela, Romy

Guelas, Romeo Anaya, Octavio (Famoso) Gomez, Julio Guerrero and Antonio Gomez.

Ruben

Navarro said of Chacon: “Bobby is one of the best fighters around. He’s strong

and he fights strict. I like to spar with him because he gives me a good

workout.”

Sure

enough, Bobby Chacon was sensational. He was still two months shy of his

twenty-third birthday when he won the vacant WBC featherweight title from

Alfredo Marciano in 1974. But it was Chacon the old hand, the blistered veteran

bruised and battered by the lumps of a turbulent life, who would thrill us with

a succession of never-say-die epic performances.

The

undisputed apex of that cycle was his fourth and final set-to with old foe

Rafael Limon. Their first battle had ended in a decision for Limon, their second

in a technical draw, their third match in a split decision victory for Chacon.

Feelings ran high between the two warriors, and they were not feelings of

immense affection.

Some

mischievous soul, I swear, must have visited Bobby and Rafael before their

Sacramento finale, run them the film of Pryor-Arguello and said: “Beat these

guys for thrills and spills and you will never be forgotten.”

Somehow,

some way, Chacon and Limon stepped up to the plate and just kept hitting home

runs. My good friend and fellow scribe, Ted (The Bull) Sares, who doesn’t wax

lyrical when the waxing isn’t justified, has never forgotten where he was and

how he reacted as Chacon and Limon hacked and chopped their way through their

staggering 15-rounds marathon.

Recalls

Ted: “First one would get rocked, then the other. Both would be floored. Bobby

was cut, bleeding profusely, pummelled and ready to go – only to come back and

score his own knockdown. Chacon got up bleeding after knockdowns suffered in

rounds three and ten to drop Limon in the closing seconds of round fifteen to

take a close but undisputed decision.

“Surely,

had Limon not gone down, Bobby would not have won. I lived in Boston at the time

and recall leaping up from my chair, spilling beer and food all over the place

and on my friends, and screaming unabashedly at the top of my voice, ‘Get him,

Bobby, get him, knock him out!’ And get him he did. The scoring was: Judge Angel

L Guzman, 142-141, judge Carlos Padilla, 143-141, and judge Tamotsu Tomihara,

141-140.

“This was

the fight that turned me from dedicated boxing fan to full fledged addict. This

fight, the essence of which was toe-to-toe, ebb and flow, back and forth action,

was breathtaking and I mean that quite literally. It was as close as two

fearless men can get to death, to the edge if you will, and still survive.

“Limon

actually had a strange smile on his face as he was knocked down for the last

time and was getting up. I swear on a stack of bibles that he smiled at the

crowd. It was almost mystical, surreal, whatever label you could put on it. All

I know is, I will never forget the fifteenth round of that fight.

“I

remember Bobby saying, ‘I broke down after the Limon fight. I didn’t like that

guy to begin with, and with everything that happened…. I couldn’t sleep,

couldn’t eat….’”

Chacon, in

typical storybook fashion, couldn’t have timed his final charge more finely or

dramatically. He staggered Limon with a right to the head in those dying seconds

and then knocked him down with two more short rights in mid-ring. At the bell,

Limon was on his feet, taking an eight count and hovering with strange and numb

pleasantness in his own private twilight zone as blood ran from his mouth.

“I wanted

to win any way I could,” said Bobby Chacon.

The fight

of the year for 1982? Yes, I believe it was. No doubt others will tell me I’m

wrong and cast their vote for the storming battle between Mr Pryor and Mr

Arguello at the Orange Bowl.

C’est la

vie!

> The Mike Casey Archives

<

|