The Jewels In

Jerry’s Crown: Quarry at his very best

By Mike Casey

When you got past the marriage problems, the managerial changes

and the hard luck circumstances, you came upon the greatest problem of all with

the talented Jerry Quarry: his head. What went on in Jerry’s mind was always the

major factor, the greatest frustration, the toughest opponent.

In his straight talking way, boxing’s eternal Comeback Kid from

the Los Angeles suburb of Bellflower always acknowledged his biggest failing.

After boxing with admirable prudence and restraint to score his greatest victory

over the dangerous Ron Lyle in 1973, Quarry sat in his dressing room and jabbed

a finger at the tough old melon atop his muscled shoulders and thick neck. “The

big difference with me as a fighter now is right here,” he said.

Ah, but it wasn’t. Not really. And we probably wouldn’t have

loved him half as much if it had been. Jerry’s volatility was the principal and

oddly loveable reason for his magnetism. We kept tuning into the next episode

because we had to see whether he would finally put the pieces together and cross

the finishing line.

In the crucial fights of his career, Quarry belied his undoubted

ring intelligence by employing the wrong tactics when his fierce pride

gridlocked his fighting brain. He was the thoughtful counter puncher who chose

to slug it out with the prime slugger of the age in Joe Frazier. He was too

careful and too patient with smart cookie Jimmy Ellis.

But it was never as simple as that with Jerry. Aside from the

strategic errors, there was ill fortune and the occasionally unfathomable. He

was the victim of genuine bad luck in his first fight with Muhammad Ali and

ambushed by the downright bizarre in his stunning loss to George Chuvalo.

Even on his winning nights, Jerry would sometimes look listless

and distracted, as if his opponent was the least of his tormentors. Like poor

old Jacob Marley in ‘A Christmas Carol’, one imagined Quarry dragging a great

chain in his wake for his sins.

Colourful

Jerry Quarry was a colourful, good-looking Southern Californian

of Irish descent, whose erratic ring form constantly bewildered his critics and

even his most ardent fans. He would counter exasperating defeats with

spectacular victories and send his supporters yo-yoing from joy to despair and

back again.

He seemed to relish being written off, for that was when he

produced his greatest performances. Praise and acceptance seemed to have the

reverse effect, bringing out the negative side of his personality and shattering

his ambitions at the most untimely moments.

From the beginning of his career, Quarry was hailed as a

potentially great heavyweight, and on his better days he justified such praise

by beating some of the finest men in the business. Again and again, he

manoeuvred himself tantalisingly close to the world championship, only to

stumble and fall in the crucial fights. He could win the pennant but he could

never make it through the play-offs.

Such setbacks reminded us of the only real chink in Quarry’s

armour: the jumbled mind that all too frequently jammed the controls of an

otherwise formidable fighting machine. That mind would only become unclogged

when penetrated by harsh criticism or the implication that its owner didn’t have

what it takes. Then Jerry would shake himself down and show the world his great

talent.

Quarry’s failure to reach the pinnacle of his profession is an

everlasting tribute to his incredible allure. He possessed that special charisma

that the gods normally reserve for only a handful of champions. When a certain

boxing publication conducted a popularity poll of past and present day fighters

in the early seventies, Quarry’s name ranked alongside those of Jack Dempsey,

Rocky Marciano and Muhammad Ali.

Jerry’s inconsistency could be infuriating, yet his chances

against any man could never be discounted. His disciples kept the faith because

Quarry always seemed on the verge of catching fire and realising his magnificent

potential.

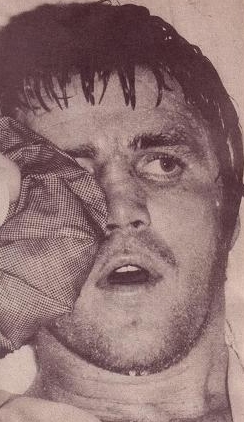

He had all the necessary physical attributes at his disposal. He

looked every inch a fighter, a rock of a man with a thick chest, powerful

shoulders and solid legs. He had a powerful punch and a good chin. He was tough

and rugged, very much the All-American boy in his early days with his close

cropped hair and crooked smile.

But the rain clouds always seemed to home in on Jerry.

Inevitably, he inherited the ‘Great White Hope’ mantle, with which he felt

genuinely uncomfortable. There was the hate mail from obsessive fans who

expected too much. There was the family and in-laws who trailed along with him

to all his fights.

The story goes that father Jack Quarry laced gloves on Jerry when

his son was just five years of age. When other kids bullied him, Jerry would

stand his ground and fight back. As an amateur, he once said, “I feel a great

challenge every time I get into the ring. I feel that I am fighting for my life

and I must win.”

Let us not forget that Jerry Quarry did win a lot of important

fights too, mostly as the underdog. He won them in style and he won them

thrillingly. The Bellflower Belter at his very best was something to see.

Thad Spencer

Thad Spencer, out of Portland, Oregon, was the coming man. He had

soared to number two in The Ring ratings and many believed he had the beating of

Joe Frazier in the heavyweight scramble for supremacy that followed Muhammad

Ali’s exile into limbo in 1967. While Muhammad would scrap with the Army draft

board and the courts for the thick end of three years, the young tigers in his

wake would chase the prized crown.

Spencer was a good stylist with a solid punch who had compiled a

32-5 record and accounted for the respected likes of Roger Rischer, Billy

Daniels, Brian London, Doug Jones and Amos ‘Big Train’ Lincoln. There was

nothing sensational about Thad, but he was knocking off the right men and

getting the job done.

When the WBA organised its eight-man elimination tournament to

find a successor to Ali, Spencer got off to a flyer with a unanimous win over

the long-time leading contender, Ernie Terrell. Jerry Quarry, by contrast, only

squeaked past former champ Floyd Patterson on a controversial decision.

Jerry was a 7 to 5 underdog when he squared off with Spencer on

February 3, 1968. Thad was the heavier man by seven and a half pounds at 200 ˝,

but Quarry was a revelation as he systematically tore the Oregon man apart. The

cheers and roars from the crowd of 12.110 thundered around the Oakland Arena as

Jerry took control and set up an epic finish.

He floored Spencer in the fourth round with a looping left hook

to the chin and again in the tenth with a short, chopping right to the jaw. In

each case, there were only seconds remaining in the round as the crowd went

wild. Referee Jack Downey, distracted by the cacophony of sound, continued

counting to the mandatory eight on both occasions.

Quarry cut the coup de grace just as fine. There were just three

seconds left in the twelfth and final round when he jumped on Thad like a tiger.

Jerry lashed Spencer with a tremendous barrage of punches, but the significant

blow was a big right to the head that set Thad wobbling and scattered him into

no man’s land. Spencer tried to clutch and survive but he couldn’t shunt himself

out of the line of fire as Quarry rifled lefts and rights to the head to force

referee Downey’s stoppage.

Thad Spencer was never the same fighter again. He had eight more

fights and lost them all.

Quarry was jubilant and spoke with the confidence of a man who

was just weeks away from fulfilling his dream. “I just fought a smart fight and

it paid off,” Jerry said. “He hit me one good shot in the whole fight, a left

hook in the fifth round that hurt. I told everybody I’d prove I was faster than

he was. I knocked him down with the right, which they said I didn’t have.”

Little more than two months later, Jerry was back at the Oakland

Arena for the big one against crafty Jimmy Ellis. It was a fight that Quarry

could have won and really should have won. You look at the tape even now and

wonder why Jerry kept holding back in a close fight that was his for the taking.

He still got a draw from judge Rudy Ortega, who saw it 6-6-3. But Elmer Costa

scored it big for Ellis at 10-5, while former champ Fred Apostoli also had Jimmy

winning by 7-5-3.

Quarry suffered a back injury and was in a body cast for weeks

afterwards. It was the beginning of a long cycle of frustration.

Buster Mathis

By the time he got to big Buster Mathis on March 24, 1969, Jerry

had done little to convince the fight fraternity that he had any new tricks.

Ring editor Nat Fleischer admitted to giving up on him. Jerry had eased his way

back since his back injury, posting four wins against modest opposition in Bob

Mumford, Willis Earls, Charlie Reno and Aaron Eastling.

Mathis, a goliath of the age at 234 1/2lbs, was pitting his

deceptively skilful bulk against Quarry’s 196. Buster was in the form of his

life, having suffered just one defeat in his 30 fights, a brave and honourable

loss to Joe Frazier at that. Buster was unfairly derided in some quarters for

being something of a cartoon character, but he was a fine boxer and an immensely

difficult man to knock over. Frazier had hacked at him for the best part of

eleven rounds before finally felling him like a big oak tree.

Mathis had reeled off six victories since that derailment,

including a bloody and emphatic points win over George Chuvalo just a month

before meeting Quarry.

Buster was a 12 to 5 favourite over Jerry when they clashed at

Madison Square Garden. The scuttlebutt on the fight beat was that Quarry was

incapable of changing his style and would be picked off and possibly stopped by

Mathis.

Jerry loved that kind of talk. It had the effect of a liberal

shot of Scotch firing through his blood. From the opening bell, the cautious

counter puncher turned downright vicious. Yet there was nothing reckless or

needlessly cavalier about the boxing lesson that Quarry gave Mathis.

Establishing his authority from the outset with a charging

two-fisted attack, Jerry settled down to fashion an aggressive but intelligent

performance. Piece by piece, he took Buster apart, switching the attack from

head to body and wearing down the big man’s body.

When Mathis split his black velvet trunks down the back in the

second round, it was the least of his problems. A left hook to the side of the

head from Quarry shuddered through Buster’s body and finally cut the right wire.

Mathis hovered momentarily in his dazed state and then dropped to one knee near

the ropes. Jerry saw his chance to end the fight early but was too eager in his

subsequent attack and failed to find the payoff punch before the bell. He didn’t

have the KO but he had Buster’s number.

It was a virtuoso performance on Quarry’s part. He capped it by

bloodying Buster’s nose in the tenth and by dropping his hands and inviting the

big man to hit him in the eleventh.

The fight wasn’t a shutout for Jerry, but it was the next best

thing. Judges Jack Gordon and Tony Castellano tabbed it 10-1-1 for Quarry, while

referee Johnny Colan saw it 9-2-1.

“A man that size has to be weak in the body and I just took

advantage of it,” Quarry said.

Nat Fleischer certainly changed his opinion of Jerry, commenting,

“I saw Quarry, a 12 to 5 second choice, take Buster Mathis apart the way a top

flight automobile mechanic will unscramble the components of a delicately made

Ferrari. Not that Buster is delicately made.”

Mac Foster

By the dawn of the seventies, Jerry Quarry had one foot in the

last chance saloon as a major league player. What should have been a golden year

in 1969 had gone steadily downhill after his masterful performance against

Mathis, ending in disaster and near farce.

Jerry got it into his head that he could beat Joe Frazier in a

head-to-head slugging match in an audacious bid for Joe’s version of the

heavyweight championship. It was certainly a treat for the fans, and the opening

frame of that memorable war went into the record books as the round of the year.

But Quarry’s tactics against a great brawler in the prime of his life only

served to bring Jerry the limited glory and lifespan of a kamikaze pilot. He was

savagely beaten in seven rounds on a fiercely hot New York night and then thrown

out into the cold six months later when he staggered into the surreal mire of

George Chuvalo’s winter wonderland. Seemingly heading for a points win, Quarry

was knocked down by a Chuvalo haymaker in the seventh round, arose at the count

of three, dropped back to his knee to clear his head and then missed referee

Zach Clayton’s cry of ‘ten’. Man, did Jerry holler in his dressing room after

that one. The entire world was against him.

When Quarry came into his fight against the highly touted Mac

Foster at Madison Square Garden on June 17, 1970, the badly tarnished ‘Great

White Hope’ had notched just two meaningless wins since the Chuvalo disaster. A

second round bombing of the little known Rufus Brassell had been followed by a

laboured points win over that tough old journeyman, George ‘Scrapiron’ Johnson.

Mac Foster was the new kid in town, all the way from Fresno,

California, having won all of his 24 fights by knockout. Like his fellow

prospect, the young George Foreman, Mac had feasted mainly on weak opposition,

but he had vaulted to the number one spot in The Ring ratings. Some kind of

tasty trailer invariably heralds the arrival of such a hot young heavyweight

prospect, and the story about Foster was that he had reportedly knocked the

ageing Sonny Liston unconscious during a sparring session.

Whatever the true quality of Mac’s credentials, he started a 7 to

5 favourite over Quarry, out-reached Jerry by nine inches and outweighed him by

14lbs.

But Foster was suddenly in New York, at the Mecca of boxing

itself. Despite his lofty ranking, he was also taking his first dip into genuine

world class. It was an entirely different scenario from the gentler fight towns

of Fresno and Houston and the simpler business of knocking over the likes of the

jaded Cleveland Williams.

Mac was cautious from the opening bell against Quarry. Keeping

Jerry at bay with a raking, tentative jab, the bomber from Fresno kept his power

in the locker. Only occasionally did he venture a left hook to the head, and

Quarry quickly picked up the scent of fear and uncertainty. By the fourth round,

Jerry had got his bearings and formulated the appropriate game plan. From the

fourth round, he began to move in and attack Mac’s body with sudden flurries,

looking to rough up the big man.

Foster seemed confused by Quarry’s raids, which included some

meaty hooks to the body. Jerry worked busily on the inside in the fifth,

softening his opponent and teeing him up for the big onslaught that would

follow.

Quarry sensed the time was right in the sixth round and went to

work in earnest. Foster’s ineffective jab was giving him no protection and his

ignorance of how to survive in the major league became alarmingly apparent.

Jerry began a sustained assault, forcing Mac to take flight. But

Foster couldn’t find a place to hide, and a countering right hand smash pushed

him nearer to the cliff’s edge. He slipped and nearly toppled over in a neutral

corner and then found himself trapped on the ropes as Quarry let rip and

unleashed the big bombs. Somehow Foster extricated himself, but Jerry pursued

him to the opposite corner and drove home the payoff blows. Mac collapsed onto

the ring apron, shattered and bleeding from a cut to his face. Referee Johnny

LoBianco reached the count of three before signalling the end of the fight.

Ron Lyle

Was there ever a better Jerry Quarry than the cool and

disciplined boxing master who gave the thunder-punching Ron Lyle such a

brilliant lesson in the noble art? Everything had altered for the better in

Jerry’s muddled life by the night of February 9, 1973.

Radical changes had been a necessity. Nearly three years after

the Mac Foster triumph, Quarry had been twice beaten by Muhammad Ali and had

failed to balance the scales with uninspired points wins over Dick Gosha, Tony

Doyle, Lou Bailey and Larry Middleton. Only a first round blitz of British

champion Jack Bodell in London had seen Jerry at his fiery best.

His muddled private life and marriage problems had spiralled out

of control and driven him to the point of despair.

Switching his base of operations from Los Angeles to New York and

placing himself under the shrewd tutelage of Gil Clancy, the calmer and more

mature Quarry gained a new lease of life and entered the golden phase of his

turbulent career.

Gone was the fresh-faced, crew cut kid, supplanted by a tougher

and worldlier man. So long had Jerry been hanging around, you had to remind

yourself that he was still only twenty-seven.

He must have experienced a distinct feeling of deja-vu when he

checked out the dossier on Ron Lyle. For here was another big man, another big

puncher with an unblemished record, another hot shot on a roll. But big Ron

would thrillingly prove in the years ahead that he was no false alarm. He was a

better, tougher, harder fighter than Thad Spencer, Buster Mathis and Mac Foster

ever were.

Ron started late in the professional ranks after a seven and a

half-year prison term for second degree murder, but he hit the ground running.

He had steamed to 19 successive victories and only Leroy Caldwell and Manuel

Ramos had taken him the distance. Lyle, under the guidance of trainer Bobby

Lewis, had been matched sensibly against a group of name opponents who were

either on the slide or ripe to be picked off. Among Ron’s knockout victims were

Jack O’Halloran, Bill Drover, Chuck Leslie, Scrapiron Johnson, Vicente Rondon,

Buster Mathis and Luis Faustino Pires.

However, Lyle’s most recent triumph was a victory of genuine

quality, a third round demolition of Larry Middleton, who had given Quarry a

tough distance fight in London just seven months before.

So Jerry was back at his old stomping ground at Madison Square

Garden, now an adopted New York son, but otherwise smack in the middle of a

familiar old scenario. He was the lighter man by 19lbs at 200lbs even. He was

the whipping boy with the golden name that would look great on Ron Lyle’s hit

list. Others had tripped and stumbled over the apparent carcass that was Quarry,

but the dead man walking would surely have the decency to follow the script this

time. He was coming off a somewhat laboured TKO of Randy Neumann, and dear old

Randy was no Ron Lyle.

This, then, was the backdrop. You could almost hear Jerry

chomping at the bit.

What followed was an astonishingly authoritative and overwhelming

performance. Trainer Gil Clancy, who had patiently drummed the importance of

self-discipline into Quarry, must have gone to seventh heaven on that memorable

February night. How often does any fighter follow a structured game plan to

perfection? Jerry was sensational.

A certain, tight atmosphere lingers over a crowd when it expects

an underdog to be crushed, like the eerie silence in the midst of a storm that

precedes the next clap of thunder. Quarry went to work in such an atmosphere

that night and made hay. He marked his territory in the opening round when he

missed with a left hook and then shot a right to Ron’s head that made the big

man’s knees dip.

Jerry never looked back as he fought shrewdly on the outside and

planned his sudden raids with immaculate timing. Another short right in the

fifth round buckled Lyle’s knees again, but Quarry was beaten by the bell as he

followed up with a salvo of shots to the head.

Jerry continued to shake Ron with rights and flashing left hooks

to the head as the shockingly one-sided fight wore on. Lyle’s feet seemed

cemented to the canvas as he was skilfully picked off and rattled by a much more

worldly and intelligent foe. Any chink of light for Ron quickly disappeared. He

was getting the better of things in the eighth round when Jerry suddenly sent

him reeling with a big left hook and pounded him with a succession of shots

before the bell.

When it was all over, Quarry had breezed home in the performance

of his life. Referee Wally Schmidt saw a closer fight than most, returning a

7-4-1 card. Judges Bill Recht and Tony Castellano tabbed it 9-1-2

and

10-2 for Quarry respectively.

In his dressing room, a jubilant Jerry couldn’t resist crowing

and rubbing a few faces in the dirt. “I’m not finished and I don’t have to go

into another trade like some people said I should. I proved that. Everybody puts

me down because I lose the big fights. They say I just beat the bums. They’re

crazy as hell. I think Ronnie sitting right here is one helluva fighter.”

Earnie Shavers

A certain fellow from Warren, Ohio, was also one helluva fighter

on his night and one helluva puncher into the bargain. Earnie Shavers was out to

wreck Quarry’s perfect year of 1973 when the two men faced off at Madison Square

Garden on December 14.

The stats boys loved to number crunch Earnie, because the

exercise didn’t require too much exertion. He had lost only two fights and

knocked out all but two of his 47 victims. Shavers was a banger and how he could

bang. He had wrecked the clever Jimmy Young in three rounds and was coming off a

one round blitz of former WBA champ, Jimmy Ellis.

Then Earnie met Jerry and it was all over in two minutes and

twenty-one seconds. Riding high and full of confidence, Quarry crashed a left

hook to the temple of Shavers and sent him staggering into the ropes. Always a

clinical finisher, Jerry kept firing as Earnie descended into the abyss. A right

to the face sent Shavers down, scattering his mind and taking the life from his

legs. He got up unsteadily, reeled into a corner and was rescued by referee

Arthur Mercante.

Everyone was hugely impressed by Quarry’s performance, including

world champion George Foreman, who agreed that Jerry was a deserving challenger.

How the fans clamoured for a Foreman-Quarry showdown!

Well, Big George never did fight Juggernaut Jerry, and perhaps it

is just as well. Would Jerry have won? No.

Alas, for the same old oddly endearing reason.

> The Mike Casey Archives

<

|