Whirlwind:

Pancho Villa Was Dempsey In Miniature

By Mike Casey

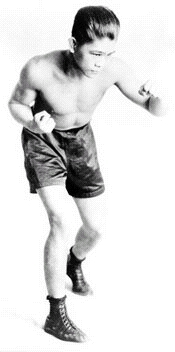

He didn’t look like the explosive flyweight champion of the world

that boxing had come to know. What was wrong with Pancho Villa? His punches

lacked steam and he seemed uncharacteristically reluctant to seize the

initiative. This precocious young Irish kid called Jimmy McLarnin was jabbing

and moving and skating ahead on points.

The puzzled crowd at the Emeryville Ballpark in California

couldn’t quite understand what was unfolding.

Where was Villa’s famous dynamism? Where were the whirlwind

attacks and the bursts of ferocious punching that constituted his glorious

trademark? Pancho’s many thousands of fellow Filipinos in the crowd kept

awaiting the catalyst for the explosion that would set their great hero off and

see him sweep McLarnin away. It never came.

The connoisseurs knew that Jimmy McLarnin was much more than just

another young prospect. He was a revelation, a boy wonder who was still five

months shy of his nineteenth birthday and for whom great things were being

predicted. But Pancho Villa was surely a bridge too far for Jimmy at such a

tender stage in his career. Surely he couldn’t beat the great Villa, not even

with a six-pound weight pull.

Those in the know had been divided before the fight and now it

was the acknowledged dean of sports writers, Damon Runyon, who was beginning to

look as if he had picked a wrong ‘un.

“Pancho Villa is the best fighter of his weight in the world,”

Runyon had said. “He is even greater as a flyweight than Dempsey is as a

heavyweight.”

As a personal friend of Dempsey, it hurt Runyon to make that

comparison, just as it had hurt him to bet on Luis Angel Firpo against Jack

after being tempted by deliciously juicy odds.

But everyone got the gist of what Runyon was saying and few

doubted that Pancho Villa, a remarkable and charismatic ball of eclectic energy,

was an exceptional talent.

Great fighters can be beaten, however, and Eddie Graney believed

that Jimmy McLarnin was the man to beat Villa in the circumstances. Graney, one

of the foremost referees of the time, had watched both boys in sparring and

said, “No fighter can give McLarnin six or seven pounds advantage and expect to

win. That includes Pancho Villa, flyweight champion of the world.”

So it proved, with McLarnin boxing his way to a ten rounds points

victory that came as a major shock to the crowd at the Emeryville Ballpark.

Jimmy, for all his glowing potential and quick progress through the ranks, was

virtually unknown on the West Coast. He had been an overwhelming second choice

in the betting.

Such was the impact of his triumph that he and manager Pop Foster

were besieged by offers. Yet the lingering spectre of the sluggish and lethargic

Villa wouldn’t go away.

Nobody thought much of it in the early going as the 24-year old

champion sized up McLarnin and did little work. The consensus of the watching

fans was that they were merely watching the lull before the storm. Pancho looked

his usual sinewy and simmering lean self at 115lbs, while Jimmy was coming into

the ring at 121. Fighting bigger opponents was meat and drink to Villa, and his

supporters didn’t attach much importance to the weight difference.

Then the first disquieting signs became evident. There was

something wrong with the champion, something that was clearly evident in his

demeanour and movement, yet impossible to pinpoint. He was making no great

effort to engage McLarnin in what was quickly becoming an oddly quiet duel of

posing and feinting.

Villa’s slothfulness fooled even McLarnin’s cornermen for a

while. They advised Jimmy to hold back and box cautiously, being aware that

Pancho was a ‘flash fighter’ who would follow moments of quietness with sudden

and explosive bursts of punching.

McLarnin, with the impatience of youth, quickly grew tired of the

waiting game. Assuming the role of the aggressor, he jabbed Villa with long,

stinging lefts. Pancho seemed irritable and flustered and his work was ragged

and ill-timed when he was sufficiently riled to lash back at his youthful

tormentor. When Villa rushed, Jimmy’s defensive skills and fleet-footedness

would take him safely out of range. On more than one occasion, Pancho mistimed

his charge completely and fell into the ropes. He would often miss McLarnin with

two or three punches in succession.

Villa was but a shadow of the ferocious buzzsaw that had so

ruthlessly cut through the great Jimmy Wilde just two years before. Pancho’s

temperament was also betraying him as he became increasingly exasperated by his

failure to trap and hurt Jimmy. McLarnin was protecting himself well in the

clinches as he skilfully blocked Pancho’s attempted jolts to the kidneys.

It was all too much for the proud Villa, who finally lost his

temper in the fifth round as he missed with two rights and then back-handed

Jimmy in the face through sheer frustration. That infringement brought a stiff

warning from the referee, but it didn’t produce any improved or constructive

work from Villa as the great mystery continued.

Nobody had seen the Filipino sensation being so comprehensively

outmanoeuvred. He couldn’t outbox the Irish kid or even out-hit him. Jimmy kept

penetrating Pancho’s defence with spearing jabs and checking him with counter

punches.

The expectant Filipino contingent watched the rounds drift by in

confused disbelief, forever waiting for their Pancho to open up in earnest and

blow the young Irish upstart from the stage. In fact Villa might just have edged

the third round and that was his lot by the time the race had been run.

Jimmy McLarnin celebrated joyously and was swept off to a number

of victory parties. Pancho Villa said he didn’t feel well. Not too many people

believed the little fellow.

In fact he was suffering from a badly poisoned jaw after having a

wisdom tooth extracted and had not slept for the last two nights from its

terrible and persistent pain. The infection to the jaw had become so advanced

that the muscles had set and could only be relieved by a surgeon.

Billy Roche

Famous old referee Billy Roche had a great affection for Pancho

Villa and his flamboyant fighting style. Commenting on the ultimately tragic

sub-plot to the McLarnin fight, Roche said: “Villa never should have been

permitted to go through with that bout. Just prior to the encounter, he had a

troublesome wisdom tooth extracted. Complications developed and Pancho entered

the ring a very sick lad.

“For ten gruelling rounds, he waded into the heavier McLarnin.

The decision went to McLarnin. Villa left the ring and returned to the dentist’s

chair. More teeth were extracted and Pancho was told to return the next day for

further treatment. Instead he threw a wild party, which lasted several days. The

wounded jaw was forgotten, neglected. Blood poisoning set in.

“Pancho, ordered to a hospital, refused to go. The condition

became acute and he was rushed to the operating table on which he died on July

25, 1925.

“If Pancho Villa had a fault, it was that he was too game for his

own good.”

At the hospital in San Francisco, Dr CE Hoffman reported that

Pancho had died under the anaesthetic. Hoffman was preparing to operate when

Villa’s heart stopped beating.

Billy Roche preferred to remember the vibrant and tireless little

killer of the ring who was born Francisco Guilledo and was a mere 80-pounder

when fight promoter and manager Frank Churchill discovered him in the

Philippines.

Recalled Roche: “Pancho Villa packed as much personality into his

little brown body as Jack Dempsey. The boy who popularised the Filipino fighter

was a little Manassa Mauler, a vicious, rip-snorting hooker who went fifteen

rounds at blinding speed and finished apparently as fresh as he started.

“A scant inch more than five feet, weighing 109 pounds at his

best, with a swarthy skin and coal black hair sleeked straight back after the

fashion of a Hollywood sheik, Pancho the Puncho looked more like a doll than a

fighter. But he was built like a Sandow, endowed with amazing strength and

stamina.”

My good pal and boxing analyst, Curt Narimatsu, from the Aloha

State of Hawaii, is a great and enthusiastic student of Pancho Villa. Curt is no

less an admirer of the fighting spirit of today’s Filipino tornado Manny

Pacquiao, but is quick to pour cold water on the suggestion that Manny is

another Pancho.

Here is Curt’s assessment. “Pete Sarmiento, another Filipino

fighter and a peer of Villa, put it best when he said that Pancho’s greatest

assets were his speed and quickness. These are Manny Pacquiao’s best assets too,

but Villa was faster and quicker.

“Watch the film of Villa against Johnny Buff. Villa is a

lightning blur as opposed to Pacquiao’s easily discernible punch trajectory and

movement. No, the herky-jerky old film is not the reason for this. It is Pancho

Villa’s innate athleticism.

“Like Manny Pacquiao, Villa was resilient and punch-proof. Unlike

Manny, Pancho was outweighed by most of his foes. Lost in history is the

fountainhead of comparison between Villa and Gaudencio Cabanela. Like Villa, Cab

was outweighed by his Australian foes.

“Cab’s greatest asset was his speed. It’s a cliché, but Filipino/Pinoy

fighters are typecast as fighting chickens, quick movers but with no real power

or definitive wallop. This is a resonant stereotype throughout Asia.

“Villa and Cabanela reversed that myth and so does Manny Pacquiao.

All have wallop, providing that they are fighting guys of their own size.

“I rank Pancho Villa on the cusp of my Top 20 all-time

pound-for-pound greats, in the close company of Charley Burley, Jim Jeffries,

Barney Ross and Jimmy McLarnin.

“As a point of comparison, I would see Villa outboxing Ricardo (Finito)

Lopez in much the same way as Sugar Ray Leonard outboxed Randy Shields. We are

talking about a different calibre of speed and quickness.”

Curt Narimatsu’s mention of Pete Sarmiento is an interesting and

relevant reference. Pete was a fair old scrapper in his own right, packing an

incalculable number of official and unofficial fights into a hectic, twelve-year

career. He was good enough to take Villa all the way before dropping a fifteen

rounds decision to Pancho in their April 1922 fight in Manila. Like Villa,

Sarmiento’s appetite for life was as voracious as his appetite for fighting.

In 1943, long after his career and his money were spent, Pete was

working in a shipyard when he dropped a line to his old pal, Damon Runyon. Damon

quite obviously admired the Sarmiento spirit, writing: “Sarmiento was one of a

group of Filipino fighters who came to the United States in the mid-twenties to

display that racial tenacity and courage that only recently was demonstrated in

fire and blood on Bataan Peninsula.

“Sarmiento was a buzzsaw in action, noted for the fact that he

never clinched. He licked four world champions in non-title bouts, Joe Lynch,

Abe Goldstein, Eddie (Cannonball) Martin and Charley Phil Rosenberg, fought

upwards of 300 battles, made perhaps $300,000 and spent it all.”

The tireless Sarmiento fought some other notables too, including

Tony Canzoneri, Bud Taylor, Benny Bass, Memphis Pal Moore, Carl Tremaine and

Bobby Wolgast.

Johnny Buff At Ebbets Field

After clearing up the competition in his native Philippines,

Pancho Villa came to America and immediately created excitement and glamour as

he swept to a series of impressive wins in New York and New Jersey. The only

real thorn in Pancho’s side as he steamed towards a championship fight with

Jimmy Wilde was Frankie Genaro, the little New York master possessed of

wonderful boxing ability.

There were not too many men, however, who could outsmart Villa.

Much like Dempsey, Pancho was equally adept at handling fellow punchers and

evasive cuties. Few were cuter than Johnny Buff, who had stepped up a division

to win the bantamweight championship from the great Pete Herman. After

surrendering that title ten months later to Joe Lynch, Johnny returned to his

natural domain of the flyweights to take on Villa at Ebbets Field in Brooklyn on

September 14, 1922.

Buff was facing an extraordinary eighteen-year old who seemed the

nearest human equivalent to a typhoon. Although Johnny was a somewhat jaded

veteran by that time, Villa’s victory still stunned the boxing fraternity as he

secured the American flyweight championship with a performance of incessant

fury.

Villa dominated the battle from the outset. All coils and

springs, there didn’t seem to be a moment when he was still or idle. While the

cautious and knowing Buff waited patiently for the right openings, Pancho

punched almost continuously, gradually dismantling Johnny with a withering body

attack and hammer-like jabs and hooks to the head.

Buff simply couldn’t get set to mount a meaningful counter

attack. He attempted to thread punches through the oncoming blizzard, but

Villa’s speed and sheer work-rate consistently swamped Johnny’s best efforts.

From the sixth round, Pancho began to try for the knockout, but

Buff still possessed much of his old defensive skill and employed some effective

blocking. The tiring American must have known that his game resistance was only

serving to postpone the inevitable landslide, yet he revived a little in the

middle rounds as he appeared to come through the shock of Villa’s early

onslaughts.

But typhoons and hurricanes can be cruelly deceitful. They are

not always through when they appear to be. The storm came full circle and

whipped up again as Villa pounded Buff on the ropes in the seventh round and

then battered him around the ring in the ninth.

In the tenth frame, courageous Johnny finally began to fall apart

as the charging Villa floored him twice. Pancho set up the first knockdown with

a two-fisted attack that saw Buff swept into the ropes and then driven across

the ring. A left to the head toppled him but he didn’t take a count. It was the

second knockdown that was of greater significance and damage. Pancho fired to

the head again and this time Johnny crumpled ominously and required the bell to

save his bacon.

Remorseless, Villa moved up a further gear in the decisive

eleventh round as he hunted his man down and sprang for the kill. Buff was

struck by a succession of hard lefts and rights to the jaw, but then pulled out

one last blow of defiance as he found Pancho’s chin and sent him staggering

back. The respite was no more than a brief interlude.

Villa forced Johnny to the ropes with a series of vicious

uppercuts, finally flooring him for the third and final time in the bout. The

towel came fluttering in from Buff’s cornermen with twenty-seven seconds of the

round remaining.

Frankie Genaro

The one man Pancho Villa could never beat was the tough and

resourceful Frankie Genaro. Frankie outpointed Pancho over ten rounds in their

first meeting at Ebbets Field in August 1922, but the real scorcher was their

return match at Madison Square Garden in March 1923.

Genaro relieved Villa of his American flyweight crown in a

sensational fifteen rounds match witnessed by a capacity crowd. Let us pause to

think about that for a second. A couple of flyweights filling the Garden!

People swarmed around the ring at the finish, and the police had

to clear a path for the boxers to exit the ring.

The tempo of the fight was terrific throughout, but it was in the

last three rounds that the battle reached new heights as the boys exchanged

punches viciously.

In the thirteenth round, they shook each other with left hooks to

the jaw, but Frankie had the edge in cleverness throughout the contest and

proved it once again with his elusiveness. Twice Pancho harried him to the ropes

and twice the American steered himself out of trouble. The pace of the fight was

still exceptional as both men fired hard and fast blows to the body.

Villa, a wonderfully never-say-die scrapper, came on strong again

in the fourteenth as he scored with solid lefts to Genaro’s jaw.

The fifteenth round was arguably the most thrilling as the two

little braves raised the bar again and launched sustained body attacks. They

slammed each other to the ribs and then Genaro wobbled Villa with a right to the

jaw. Pancho responded in kind after a clinch and the two men were still trading

at the bell.

The decision for Genaro received the thundering approval of the

hometown fans, but it would be another five years before Frankie would win the

NBA version of the world title.

For Villa, the chance to hit the jackpot came much sooner.

Jimmy Wilde At The Polo Grounds

Jimmy Wilde, the Mighty Atom, was taking a big gamble by coming

back to face the new kid in town. His legend secure but his great talent fast

dissipating, Wilde was no longer the phenomenon of yore. He had been inactive

for two years and five months by the time he defended his flyweight championship

against Villa at the Polo Grounds in New York on June 18, 1923.

Jimmy’s previous fight had been a punishing defeat to the great

bantamweight, Pete Herman, at the Royal Albert Hall in London, from which Wilde

had never fully recovered. Knocked down in the seventeenth round of that torrid

battle, Jimmy had struck his head hard on the canvas and suffered severe

concussion. Despite his lengthy rest, the injury had a permanent effect on his

ability as a fighter.

Wilde met something of a kindred spirit in Pancho, a younger,

natural born scrapper who never stopped punching and seemed blessed with

exceptional reserves of energy.

Wilde in his glorious prime of life would have had a gorgeous

set-to with Villa. As it was, the fading ghost of Jimmy was still able to wage a

morbidly thrilling, life-or-death battle against his cyclonic heir apparent.

Pancho, however, was a revelation that night and would not be

denied.

His storming attacks quickly had Wilde in disarray in a frantic

opening round, in which the Filipino’s vicious blows rained in from all

directions. Villa’s clear intent, much like Dempsey’s was to simply destroy the

other man as fast as possible. While reporters and fans recognised quickly that

Wilde was no longer the little wonder of bygone times, Villa’s performance was

still staggering in its commanding nature.

It was a horror night for Wilde, a night on which nothing went

right for the slowly drowning champion. He had to be carried back to his corner

at the end of a torrid second round after being floored by a right on the nape

of the neck, the blow apparently landing just after the bell. Wilde could have

clutched at that straw and made something of it, but didn’t do so. Stupidly

sporting? No, it was simply his way.

It is doubtful, in any case, that any respite would have altered

the complexion or the result of the fight. Wilde was enveloped in a relentless

blizzard of fast and versatile hitting. His face was quickly butchered by the

slashing effect of the oncoming punches as he bled from cuts to his mouth and

cheeks and had his right eye pounded almost shut.

He kept trying to break the rhythm of the perpetual Villa, but

Jimmy’s punches were uncharacteristically light and ineffective by comparison

and no deterrent to the whirlwind that was raging around him.

Repeatedly, it seemed that Wilde would fall as his knees sagged

and his body shook from the punishment he was taking. Villa must have wondered

what he needed to do to bring the curtain down. He kept teeing up Jimmy for the

coup de grace, but simply couldn’t finish the job of hammering the resistance

out of the amazing little Welshman.

At the close of a brutal sixth round, Wilde finally broke as he

almost fell into his corner. He was caught in the arms of his handlers,

thoroughly beaten and almost blinded by the ceaseless hailstorm. The crowd was

now screaming at referee Patsy Haley to stop the slaughter, but Wilde would not

permit his cornermen to pull him out.

Villa knew the moment of his young life had come. He rushed back

into the fray at the beginning of the seventh round to set up the knockout with

a series of fast and powerful lefts and rights to the head. Still Wilde punched

back, pulled along now by sheer instinct and bloody-mindedness. His enduring

resistance seemed to take Villa aback. Pancho broke off his attack momentarily,

as if taking stock and considering his options. In fact he had finally seen the

decisive opening.

Jimmy, desperately tired to the point of exhaustion, couldn’t

help but let his guard down and Villa was on him like a springing tiger. An

inside right cross thundered off Wilde’s jaw, and the Welshman was a dead weight

as he fell to the canvas and lay there without so much as a twitch as he was

counted out.

Jimmy was still bewildered and blinded in the sanctuary of his

dressing room, where he was unable to recognise his wife as she hurried to hug

him.

The big crowd at the Polo Grounds would never forget Jimmy

Wilde’s courage or Pancho Villa’s breathtaking, punching performance. The

Oakland Tribune reported: “The forty thousand who sat in the Polo Grounds and

saw the title pass were so captivated by the exhibition of gameness the little

Welshman gave, that for fully five minutes after it was over they sat there

quiet, waiting for him to open his eyes and come back to consciousness that he

might hear the roar that was their sincere tribute to a genuine fighting man.”

Pancho Villa earned $40,000 for the greatest triumph of his

career, while Wilde’s share of the purse was $60,000. Jimmy was quick to pay

tribute to Pancho. Said the beaten champion, “I simply met my match. I don’t

know whether I shall try to get a return bout.”

He didn’t. Sensibly, he retired. Pancho Villa wasn’t just the new

flyweight champion of the world, he was a magnificent champion at that. It

seemed that the vibrant young tiger from the Philippines would live forever.

Such is life and death.

> The Mike Casey Archives

<

|