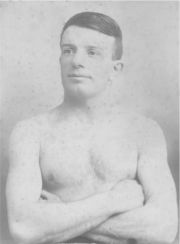

Bronx: Young Griffo,

boxing’s forgotten genius

By Mike Casey

The story goes that when Young Griffo was in the premature autumn

of his incredible life and ever more dependent on his famous love of alcohol, he

would keep himself in drinks by spreading a handkerchief on the floor of his

local saloon, placing a foot on one corner, and challenging any man in the bar

to punch him off it.

History doesn’t record how many takers Griffo had, but such were

his God-given skills and reflexes, it is probably safe to assume that he

finished ahead of the house.

Who was Young Griffo? The question shouldn’t need to be asked of

hardcore boxing buffs. But as the years rush past, so it becomes vital to

explain and justify the merits of boxing’s bygone aces to a new and eager

audience, be they genuine fans or dilettantes just passing through.

Griffo seemed to drop straight out of some fistic heaven, and

perhaps the gods were balancing the scales when they took him back at the age of

fifty-six. Boxing came as naturally to him as it did to Joe Gans, Packey

McFarland, Willie Pep and Pernell Whitaker, yet Griffo was fatally flawed, his

thirst for alcohol being both insatiable and incurable.

The irony of his addiction is that it magnified his ring

achievements, since he was frequently in some state of drunkenness when fighting

and beating some of the greatest lightweights and featherweights of his

generation. The demon drink may have shortened Griffo’s life, but it failed to

short-circuit his astonishing boxing brain.

This point cannot be sufficiently stressed and is certainly not

exaggerated. Nat Fleischer, founder and editor of The Ring magazine, once wrote

of Griffo: “He never was one to take his professional career seriously. Training

was a nuisance to him and he preferred hanging around bar-rooms and guzzling his

liquour. Seldom indeed was Griffo sober for a fight, yet so amazingly clever was

he that regardless of his physical and mental condition at the moment, he

invariably held his own or could and did whip his opponent.”

In March 1894, Griffo failed to show for a bout with Ike ‘Spider’

Weir in Chicago. The maestro was found that afternoon, drunk as a skunk, in a

local dive bar. The police officers who hunted him down hauled him off to a

Turkish bath to sober him up. Refreshed and ready to go again, Griffo gave Weir

an educated thrashing and knocked him out in the third round.

Conversation

If it were possible to bypass séance rooms and just have a good

old-fashioned conversation with those who have passed on, then perhaps George

Dixon, the legendary Little Chocolate, could be persuaded to verify Fleischer’s

assessment of Griffo. Dixon, no slouch himself for ring cleverness, was driven

to exasperation and a state of near exhaustion by trying to land a significant

blow on Griffo in their memorable contests at the Seaside Athletic Club at Coney

Island in January, 1895.

Rolling, feinting, blocking and just being a general evasive

nuisance, Griffo peppered Dixon as he pleased throughout the twenty-five round

battle, which was recorded as a draw in the era when the knockout was paramount.

However, two crucial aspects of Griffo’s make-up were evident in

the fight, two weaknesses that prevented him from crossing the final threshold

and becoming the master of his generation.

First, he couldn’t hit with any commanding power. Secondly, and

more significantly he was a cavalier spirit for whom glory ran a distant second

to having fun. Much like Max Baer in later years, Griffo wasn’t driven to stamp

his name on history or obsessed with how he would be perceived. Knowing he was

the best on his day seemed enough for him.

Carefree and unpredictable from the start of his crowded and

colourful life, it is doubtful whether he ever had a definitive game plan for

anything he did. As a young fighter, his first attempt to leave his native

Australia was typically impulsive in its outcome. Having made up his mind to

test his skills in the competitive furnace of America, Griffo set sail with a

group of other young Australian fighters in 1892. The young maestro was on his

way. Then he wasn’t. A sudden change of mind prompted him to dive overboard and

swim back to the shore. It was 1893 before he set sail again and stayed on the

ship for keeps.

Chinks

For all the mental chinks in his armour, for all the drinking

that took its slow toll on his bullish body, Griffo would lose just nine times

in his 232 recorded fights, and we will never know how many of those losses were

on the level. The mind boggles at what he could have achieved if he had been

blessed with the mental toughness and the total commitment of a Julio Cesar

Chavez or a Marco Antonio Barrera.

There was much that was mysterious and contradictory about Griffo.

Even his physique was against type. Thick set, big shouldered and almost paunchy

at times, he was as much a physical deception as Argentina’s recently departed

boxing master, Nicolino Locche.

The record books tell us that Griffo was born on March 31, 1871,

yet his gravestone in New York’s Bronx has his birth date as 1880. Even the

great man’s death was prematurely reported, although it is now fairly certain

that he died in 1927.

His real name was Albert Griffiths, and his boxing career began

as a bare knuckle fighter in his native Sydney, where he would test his ability

against the local toughs on the waterfront.

Griffo made rapid progress and his great natural talent quickly

became evident. He won the Australian featherweight title in 1889 with a points

decision over Nipper Peakes at the Apollo Athletic Hall in Melbourne, and

followed up with a fifteenth round stoppage of Torpedo Billy Murphy at the

Sydney Gymnastic Club to gain recognition in Australia and Britain as the world

featherweight champion.

Griffo had whipped a top man in the dangerous Murphy, a

big-hitting New Zealander who is credited with 78 knockouts in his 91 wins.

Griffo won their return match on a disqualification and also

notched successful defences against George Powell and Mick McCarthy.

On his belated arrival in America, Griffo outpointed Young Scotty

in Chicago and then went hunting for bigger game. In two drawn fights with

George Lavigne, the great Saginaw Kid, Griffo went through his amazing box of

tricks to make The Kid look almost inept.

Jack McAuliffe, the great lightweight legend, didn’t fare much

better against Griffo’s silky skills when the two men clashed at the Seaside

Athletic Club in 1894. Fortunately for Jack, referee Maxie Moore was a good pal

and awarded him the decision.

Such shenanigans were not uncommon in less stringent times, and

the lightweight division certainly had its share. Probably the most famous

example of blatant favouritism was that perpetuated by referee Jack Welch on

behalf of his friend Ad Wolgast, in Ad’s title defence against Mexican Joe

Rivers at Vernon, California, on July 4, 1912. When Wolgast and Rivers floored

each other simultaneously in the thirteenth round, Welch promptly lifted Ad to

his feet while he counted Rivers out.

If injustice ever ruffled Griffo, then most likely he would drink

copiously at the nearest bar and belt out any man who crossed his path. Too much

of the hard stuff certainly changed his normally genial and easy going nature.

Nor did Griffo regard alcohol as being out of bounds within the

roped square. Stories abound, though few can be verified, of the maestro

entering the ring worse for wear and having to be slapped into life by his

seconds. They needn’t have worried, for it was impossible for Griffo to look bad

once he started boxing.

However, there was one man whom Griffo couldn’t master: the Old

Master himself, Joe Gans. These titans of the lightweight division fought two

official draws, the first in Baltimore, the second in Athens, Pennsylvania,

before Joe stopped Griffo in their eighth round of their final meeting in

Brooklyn in 1900.

Information is sadly scant on how these fights panned out, but

perhaps the most significant pointer is that there are no stories of Griffo

embarrassing the great Gans.

Wiped out

In 1904, what was left of Griffo as an effective fighter was

wiped out in one round by Tommy White in Chicago. The Australian legend’s

subsequent life was a jumbled mystery, as fickle fans and writers quickly lost

track of him. He remained in America, and every once in a while stories would

circulate about his drunkenness, his arrests by the police and even the odd trip

to the insane asylum.

How did Young Griffo die? I don’t know, though I would imagine

that it was his beloved booze that finally did him in. It is sad indeed that the

trail runs cold on so many of the old-time fighters, and that the technology of

their times was either too primitive or too limited to cover their great battles

and exploits.

In Griffo’s case, we can only hope that a rare treat is yet to

come. In 1895, he knocked out Battling Charles Barnett in four rounds in New

York in what might well have been an historical first for the motion picture

industry. A short black and white film was made of the fight, directed by Otway

Latham, which was believed by the 1920s’ film historian, Terry Ramsaye, to be

the first film to be publicly projected onto a screen.

The survival status of the film is unknown, but it could just be

that Young Griffo lives on, blinding his opponent with science and taking the

odd shot of something between rounds!

> The Mike Casey Archives

<

|