| |||

| COMMENT | CONTACT | BACK ISSUES | CBZ MASTHEAD |

|

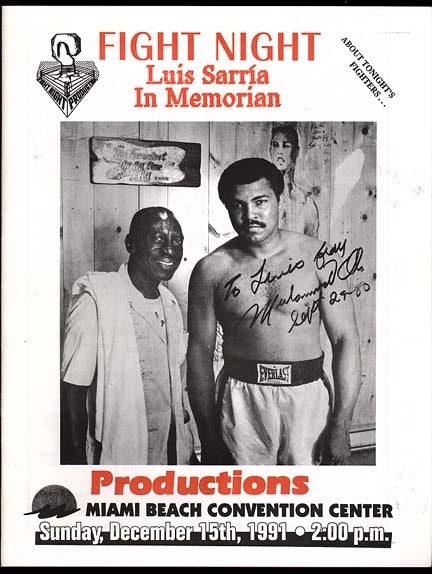

The Life and Times of Luis Sarria By Enrique Encinosa

Sports historians enthralled with the Ali legend have written little about Luis Sarria. There are reasons for such apathy. Sarria knew little English and his well-mannered, soft voice and quiet demeanor were overshadowed by the ranting of Bundini, the brilliant glibness of Pacheco and the blue-collar appeal of Angelo. The sports historians missed out on a treasure find. Luis was one of the most interesting characters in the game, considered among Cubans to be the greatest fight trainer the nation ever produced. He had wit and a dignified manner that was the mirror of his good soul. Luis Sarria was born on the 29th of October, 1911, in Cumanayagua, a farming town in central Cuba. His childhood was marked by poverty, hunger, illness and death. One of his sisters died before reaching adulthood. A brother - with whom Luis shared a bed - died in his sleep by the age of twelve, Sarria was an orphan who wore hand me down clothes and had known gnawing hunger in his belly. Many years later, when a journalist made a casual remark about having skipped lunch and feeling very hungry, Sarria smiled and said softly: “You don’t know what going hungry is like. Son, when you are hungry you can eat melted lead.” He was on his own by the age of thirteen, working at shining shoes in a street stall in the southern city of Cienfuegos. As he grew in size and strength he made good wages for very hard work during the season of the sugar harvest, wielding a sharp machete under the hot Cuban sun. He also worked in the tobacco fields of Las Villas Province, in central Cuba. Luis Sarria started in boxing at the age of thirteen, fighting in amateur smokers where a hat would be passed for the fighters and winning bettors would tip their favorites. After a few fights - mostly victories - Sarria turned pro, beating an American fighter named Ernie Balin in a four-round fight. “The money was not there,” he said about his prelim fights. “They paid a peso a round, so it was four pesos for a four- rounder. That was very little money but when I did not have any money at all, a peso could buy me a couple of cheap meals to get by another day.” Sarria fought in Cienfuegos and Santa Clara, winning most of his bouts, then headed for Havana, a very active fight center, where he set up a shoe shine stand in the porch of a café named “El Polo.” He lived in a cheap boarding house and trained at a boxing gym after working a full shift to earn a few bucks. Sarria shined shoes and sold newspapers, fighting prelim bouts for a few pesos. He scored a win over Pedro Canales and was a known fighter in undercards at Cuba’s famed Arena Cristal, a venue that had featured Kid Chocolate as one of its headline performers. For his first - and only - main event, Sarria was paid fifty pesos in 1938. His opponent was Ramon Rodriguez, an established journeyman welterweight with a decent punch and a difficult southpaw style. “It was the toughest fight of my life,” Sarria recalled in a rare interview, many years later. “He hit very hard, dropping me early, but by then I knew how to survive and it took all my skill to last the ten rounds, losing on points.” Sarria realized that his career as a boxer was going nowhere. He was a good boxer with a fighting heart, but he lacked power and his chin was ordinary. His last fight took place in 1939, when he faced Domingo Govin, a young welterweight with a hungry attitude. In the first round both men threw hard right hands and went down in a rare double knockdown. Both lifted themselves groggily from the canvas, but Sarria was the worst of the two as their seconds worked over them in their corners. “I lost by TKO in two,” Sarria said, “Referee Benitez stepped in and that was my last, my thirtieth pro fight. I won nineteen.” Luis Sarria continued to shine shoes but began a new career as a boxing trainer. A pattern was soon established: Sarria’s fighters won most of their fights. The young trainer did not allow his students to climb through the ropes unfit, nor did he overmatch them to make a quick buck. Green kids became proficient inside the ropes, and his amateur team picked up medals at tournaments. By 1943, Luis Sarria was the trainer and corner for the legendary Kid Tunero, an old Cuban pro who defeated four world titleholders, including Ezzard Charles; by 1948, Sarria was named trainer for the Cuban amateur team, winning three gold medals at the Guatemala Central American Games. The fifties established Luis Sarria as one of Cuba’s best trainers. He was the teacher and corner for three future world champions: Luis Rodriguez, Sugar Ramos and Jose Legra. Sarria also worked with world contenders including his amateur star turned pro heavyweight Julio Mederos, Spanish welterweight champion Ben Buker, lightweight Douglas Vaillant and national flyweight titleholder Amado Mir. Life was good. Luis was a respected trainer making a modest living, keeping his belly full while working at his favorite trade, but his world changed in 1959, when Fidel Castro took power in Cuba. As Cuba entered the Cold War, with guerrilla fighting and resistance movements opposing the Marxist revolution and thousands being executed by firing squads, Luis Sarria contemplated leaving his country to live in a foreign land. “Luis Rodriguez and I came to exile together,” Sarria said in an interview. “When Castro took over Cuba he abolished pro boxing but it took him a couple of years to get around to doing it and boxers were allowed to fight in other countries. Luis Rodriguez and I traveled to the United States several times. Once, after a fight, we were both alone in the dressing room and I told him, "You go back alone this time.” Luis looked at me and said “Sarria, are you staying?" And I said to him: “Yes, I cannot go back to that crap.” Luis Rodriguez looked at me and he nodded, and then said, “I am staying also. I feel the same way.” In Miami, Sarria started life once again. He was flat broke, an exile in a strange land, but he had a good reputation as an honest trainer and he had a friend in Angelo Dundee. The Dundee brothers had spent over a decade importing and exporting Cuban fighters for their Miami Beach cards. Angelo spoke chopped up Spanish and his gym was filling up with new exiles: Luis Rodriguez, Florentino Fernandez, Jose Napoles, Angel Robinson Garcia, Sugar Ramos, Jose Legra, Douglas Valliant, Johnny Sarduy and a dozen other top talents. Sarria became Angelo’s right hand man at the Fifth Street Gym. He worked with prelim fighters and future champions, as a second to Angelo and on the road with the journeymen pugs and contenders. Muhammad Ali was then Cassius Clay, a brash youth who idolized and studied Luis Rodriguez in the gym, studying the Cuban welter, copying some of his moves. “I was training Luis…” Sarria said, “And Ali spoke to me, but I do not speak English. Then he spoke to Angelo and he told me Ali wanted me to massage him…Our friendship started that day.” Sarria’s big hands kneaded Ali’s muscles. The Cuban trainer was not licensed as a masseur but decades of gym work had taught him where every pinched nerve could be softened, how to break down the body fat, how to release tension. His large hands did their magic on the fighter from Louisville and Ali understood that the soft spoken Cuban was in a league of his own. Sarria only learned a few phrases of English and Ali could say a few words in Spanish, but their language differences did not prevent both men from becoming friends, using their own sign language to communicate. Sarria became Ali’s conditioner, training the Great One, running him through endless hours of sit ups and knee bends, tuning his body while Dundee prepared the strategy for the upcoming bouts. “The Ali years were unbelievable,” he said, “I worked with him for all but two of his title fights. I was there from beginning to end. Ali treated me well. He gave me a down payment for my house and paid me a good salary, but many people around him were leeches. Angelo and the sparring partners earned their money but there were many in the camp that earned high salaries and did absolutely nothing…Few cared for him as a human being.” The sixties and early seventies were the best years of Sarria’s life. He traveled the planet with Ali, Willie Pastrano, Jimmy Ellis, Luis Rodriguez, and a squad of top talent that included top rated middleweight Florentino Fernandez and lightweight contenders Douglas Valliant and Frankie Otero. He met presidents, kings, celebrities - including The Beatles - and intellectuals including Norman Mailer and Budd Schulberg. Sarria ate at the finest restaurants in Europe and the Orient and bunked at excellent hotels in all corners of the globe. The shoe-shine prelim boy from Cumanayagua became a celebrity himself, being photographed and filmed as he worked in the gym with the Great One or stood at the corner of contenders and champions. He rode in motorcar parades in Africa, walked the ancient streets of Rome, visited the presidential mansion in Manila, felt the snow under his boots in Toronto, visited the Statue of Liberty in New York, gazed upon movie sets in Hollywood and swam at beaches in Puerto Rico, the Bahamas and Florida. He was there - at the corner of the ring with Angelo and Ferdie - when Ali fought Frazier, Foreman, Chuvalo, Norton and Spinks. Sarria was there when Rodriguez faced George Benton, Rocky Rivero, Rubin Carter, Curtis Cokes and Emile Griffith, when Frankie Otero traded leather with Buchanan and Florentino Fernandez landed big left hooks on opponents' chins. “It was incredible,” he once said, “I have a lot of tremendous memories… In Manila it was exciting. In the middle rounds Frazier hurt Ali very bad and he was in pain…Working the corner was a lot of pressure in that fight but Angelo is very smart at working a corner…I first met Angelo in the fifties when he went to Cuba almost every week for the fights…He was not rich or famous then. Like most trainers he was barely making a living.” One of the sad days of his career came when Luis Rodriguez lost a title bid to Nino Benvenuti. “Luis was a great fighter,” Sarria said, “one of the greatest I ever saw, but he was shop-worn from more than a hundred fights, yet he gave the Italian a boxing lesson until Benvenuti threw that left hook. That was the hardest punch that man ever threw. It caught Luis on the side of the jaw. When I saw Luis go down, I knew he wasn’t going to stand up that time.” In the eighties Sarria contemplated retirement. He had a home, a family and several dogs, a social security pension and Medicare, but he needed the fight game to stay alive, to feel useful. By then, the Fifth Street Gym was too far to travel for an old trainer with increasing arthritis. He needed a place closer to his North Miami home. Besides, the Fifth Street Gym had changed. Ali and the top guns of the sixties and seventies had retired, melting back into civilian life. Angelo was still active but had moved his base of operations away from Miami Beach. Ferdie Pacheco was doing TV commentary for big fights and writing books while Chris Dundee was still active with sporadic promotions and booking some fighters, but the aging Chris no longer produced the weekly fight shows that had made the gym the bubbling cauldron of pugilistic activity of its heyday. Enter Caron Gonzalez, an old friend from the time Sarria was a prelim pug. Caron was a muscular black man who had been a sparring partner of Kid Tunero and had become a very good trainer after an unspectacular and brief pro career as a welter. Caron had worked with Benny Paret and Jose Stable and was a very good teacher of infighting. Gonzalez was opening up a gym in Miami’s Allapatah neighborhood - only a block away from where Jack Britton had owned a drugstore - and Sarria was offered a chance to earn a few bucks and stay busy. Caron and Luis ran the gym for several years. Roberto Duran trained there for the “No Mas” fiasco with Ray Leonard, as did other champions including Happy Lora and Wilfredo Vazquez. Gonzalez and Sarria kept busy working with fighters like Puerto Rican lightweight Juan Arroyo, Cuban lightweight Pedro Laza and a small army of prelim fighters hailing from all corners of the Caribbean. Sarria trained fighters, massaged bodies and worked corners. He would pace himself, taking breaks in which he sat ringside, puffing on a pipe, waiting for the arthritis to ease so he could stand again, to continue teaching the nuances of the jab or hook. Eventually, he stopped working corners, for it hurt too much to climb the few steps into the ring. That was the beginning of the end of the Sarria story. All good things come to pass and so do good men. Luis Sarria is no longer among us, but those who knew him will never forget his big smile, his large hands, his soft manners and his bearing that Ferdie Pacheco equated with “the dignity of an African Prince.” Not bad for a poor shoe shine boy from Cumanayagua.

|

|

|

| Upcoming Fights | Current Champions | Boxing Journal | CBZ Encyclopedia | News | Home |