|

On the east side of the pond that is the Atlantic Ocean is a small

group of islands known variously as the United Kingdom, Great

Britain, Britain and, to many, 'Ingle-land'. We're a funny

lot, the British - not only are we unable to decide what our

nation is called, but we still believe, even in the face of

overwhelming evidence to the contrary, that we are leaders in

world sport. Granted we do probably still command the higher

echelons of the Darts and Snooker worlds but our history is, on

the whole, one of inventing sports and exporting them to the rest

of the world who then promptly beat us at them. We invented

the 'glorious game', Football - you know real football where you

kick the ball with your foot. The fact that the English

still boast of their 1966 World Cup win speaks for itself.

And then there is cricket, a sport I

canít comprehend

myself

,

and which PJ O'Rourke memorably described as 'a sport no-one

understands but the whole world still beats you at'.

Boxing was practised at ancient Greek Olympic Games but it was it

was in the 1700s that our modern sport had its origins.

James Figg, 'Master of ye Noble Art of Defence' as his business

card described him, set up the first real gym in London's

Tottenham Court Road in 1719, Jack Broughton set down the sport's

first formal rules in 1743 (among these rules incidentally

was the instruction that 'the winning man to have two-thirds of

the money given, which shall be publicly divided upon the stage'.

Imagine if we brought that one back!) and, of course, it was the

Marquis of Queensberry who set down the modern rules. Our

problems began when we let 'Johnny Foreigner' join in the fun.

Ok, these days we do have our first

British undisputed World Heavyweight champion but he spent most of

his life in Canada and is not exactly the most exciting fighter in

the world. And we can rely on the peculiar British bias

displayed by the WBO to allow us to maintain the illusion of a

long list of 'great' world champions. But these anomalies

fail to obscure the fact that, generally speaking, the rest of the

world whups our asses. The British public have, of course,

been brought up to appreciate a glorious loser more than a winner.

But occasionally a fight comes along in which the combatants bear

their souls in a display which makes all this irrelevant.

The late 1980s and the 1990s has not been the best period in

middleweight history. Yes there have been talented fighters,

Michael Nunn, James Toney and Roy Jones spring to mind, but they

either burned out, faded away or moved up in weight. 'Superfights'

failed to materialise or, when they did, proved to be damp squibs.

But in November 1990, in Birmingham England, a contest between two

British fighters proved to be the most exciting middleweight fight

of the period, indeed a fight which bore comparison to the

great middleweight fights, even the Zale-Graziano and

Hagler-Hearns classics.

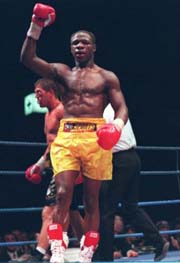

WBO middleweight champion, Nigel Benn's fighting style was very

much death or glory, knockout or be knocked out. His early

career consisted of a rampage through a series of what he called

'Mexican road-sweepers' - man of questionable ability whose role

was to be knocked over quickly and all of whom kept up their end

of the bargain. While fun to watch this left Benn largely

unprepared for his first serious test against fellow Briton

Michael Watson. Knocked out in six rounds, Benn went back to

the drawing board in an attempt to add some defensive skills to

his fearsome punching power. This was mostly unsuccessful

however as his natural tendency towards a 'tear-up' led Benn back

to the gung-ho style he had made his own. He took the WBO

title by stopping Doug DeWitt was knocked down in the process.

His first defence was a first round stoppage of Iran Barkley but

this was not the blow-out that such a result suggests, Benn being

in serious trouble himself before the stoppage. Despite this

most favoured Benn to beat the largely untested, eccentric Chris

Eubank.

WBO middleweight champion, Nigel Benn's fighting style was very

much death or glory, knockout or be knocked out. His early

career consisted of a rampage through a series of what he called

'Mexican road-sweepers' - man of questionable ability whose role

was to be knocked over quickly and all of whom kept up their end

of the bargain. While fun to watch this left Benn largely

unprepared for his first serious test against fellow Briton

Michael Watson. Knocked out in six rounds, Benn went back to

the drawing board in an attempt to add some defensive skills to

his fearsome punching power. This was mostly unsuccessful

however as his natural tendency towards a 'tear-up' led Benn back

to the gung-ho style he had made his own. He took the WBO

title by stopping Doug DeWitt was knocked down in the process.

His first defence was a first round stoppage of Iran Barkley but

this was not the blow-out that such a result suggests, Benn being

in serious trouble himself before the stoppage. Despite this

most favoured Benn to beat the largely untested, eccentric Chris

Eubank.

Taking a leaf out of the young Cassius Clay's book, Eubank created

a persona for himself which made him easy to hate. He

professed to hate the sport which paid his bills. His time

in the ring was spent posing to the crowd, going for a walk

between rounds, looking down his nose at ringsiders and generally

looking like a prat. His fighting style seemed to consist of

practising Tai-Chi stances and avoiding his opponents frustrated

attempts to land a punch on him. While untested Eubank had

shown that he was the possessor of good punching power and a solid

chin. He had really talked himself into this fight telling

all who would listen, and many who wouldn't, that he would

demolish his rival and generally getting under Benn's skin.

Eubank could be a frustrating fighter to watch as his frankly

tedious decision win over Eduarro Contreras showed.

Dismissed as a challenger by Benn's then promoter Ambrose Mendy on

the strength, or lack of it, of this performance Eubank responded

by KOing his nest opponent in twenty seconds. Even as the

referee was counting out the unfortunate Renaldo Dos Santos Eubank

was taunting Mendy, 'Bring me your boy.' When the fight was

inevitably made Eubank let it be known that he had bet £1,000 at

odds of 40-1 that he would KO Benn in the first round.

----------

The fight proved to be as much a mental as a physical battle and

from the start Eubank set out to prove his superiority. The

mind games began even as Benn climbed into the ring to be

confronted with a challenger who had stood immobile as the

champion had taken his long ring-walk and remained so - gloves

held together at chest level, in a trance-like state, seemingly

oblivious to all that was going on round him. Benn must have

wondered what he had in front of him.

The fight proved to be as much a mental as a physical battle and

from the start Eubank set out to prove his superiority. The

mind games began even as Benn climbed into the ring to be

confronted with a challenger who had stood immobile as the

champion had taken his long ring-walk and remained so - gloves

held together at chest level, in a trance-like state, seemingly

oblivious to all that was going on round him. Benn must have

wondered what he had in front of him.

Eubank began the fight in a Ken Norton-like stance and tried to

land an unorthodox lead right. When this failed he settled

into a jab and move strategy but it was a hard punishing jab

rather than a range-finder. In a clinch Benn attempted to

impress with his physical strength by lifting his opponent but the

round was Eubank's. Eubank then stalked the ring during the

interval ignoring his trainer's exhortations to sit on his stool.

Early in the second Eubank adopted a tactic he was to use for the

remainder of the fight and one which would become familiar to

British audiences for the next several years. He would stand

completely still, like a cobra ready to strike, trying to draw

Benn in. He avoided Benn's attack and countered with two

hard chopping rights.

But Benn caught Eubank too. A hard right cross tested the

challenger's chin which passed with honours. A two handed

flurry from Eubank had Benn reeling on the ropes as the bell

sounded. Early in the third Benn's left eye was showing

signs of damage but he rallied to win the round some withering

hooks to the body hurting Eubank who finished the round with blood

seeping from his left cheek. The frenetic pace continued in

the fourth which Benn also took with some ferocious punching.

But in the fifth Benn seemed unable to avoid Eubank's blows.

He tried to bob and weave but his eye by this stage was nearly

closed and Eubank's shots were fast, accurate and full of pain.

Eubank's success continued in the sixth as he again backed Benn

up. But suddenly he dropped to one knee. The crowd was

on it's feet but referee Richard Steele ruled a low blow and

replays showed Benn land a hard uppercut to the groin.

Eubank was given half a minute or so to recover but it was evident

at the start of the seventh that he had not fully shaken off the

foul's effects. Benn charged forward carelessly, ripping

hooks to the body. At one point Benn landed a series of hard

rights to his opponent's head which was locked in Benn's left

elbow. Another low blow caused Eubank to complain to Steele.

Benn laughed as he steamed forward and mocked Eubank's complaints.

Early in the eight the impression that Eubank was fading seemed

confirmed when he went down from a short right which landed behind

the ear. He again complained to Steele - he had slipped on a

patch of water - but the referee gave him the mandatory eight

count.

Benn's eye was closed as the ninth started and Eubank took full

advantage. He landed hard withering jabs and followed with

clubbing rights. Benn shouted defiance and tried to rally

but was suddenly stiffened by a brutal right and retreated to the

ropes. Eubank steamed forward and drove Benn into a neutral

corner. He landed at will as Benn's attempts to bob and

weave proved futile. Steele called a stop with four seconds

left in the round. There were tears from the now ex-champion

but no complaints. Eubank fell to his knees exhausted his

face showing the marks of battle. Both men looked like they

had been to hell and back and in a sense they had.

Eubank's

victory did not prove that he was the best middleweight

in the world, of course; he hadnít yet proved himself the best

in Britain

,

but both men had proved their courage and mettle. Each

could hold his head high as a warrior though neither would want to

prove it in such a fashion too regularly. Boxing News editor

Harry Mullan described the fight as 'the best I have seen in a

British ring' and it will be a long time before it is equaled.

Back

To WAIL! Contents Page

|