JULY 2006

01 Rinsing Off the

Mouthpiece

By GorDoom

02 Poem of the Month

By Tom Smario

03 Pollack's Picks

By Adam Pollack

04 Top Women Worth Watching

and Televising

By Adam Pollack

05 Holman Williams Belongs

in

the Hall of Fame

By Harry Otty

06 Touching Gloves

With...

"Joltin" Jeff Chandler

By Dan Hanley

07 Puppy Garcia Was

Something Special

By Enrique Encinosa

08 Muhammad's Real War

By Cliff Endicott

09 Champagne On Ice

By Ron Lipton

10 "Dick Tiger: The Life and Times

of a Boxing Immortal"

By Adeyinka Makinde

11 Floyd Patterson:

He

Always Got Up

By Ron Lipton

12 Nat Fleischer, "Mr.

Boxing"

By Monte Cox

13 "Ring of Hate"

Book

Review by J.D. Vena

14 "Gilroy Was

Here"

Book Review by Mike Delisa

15 Audio

From the Archives [mp3]

The CBZ presents another classic boxing-themed radio

show. This month we have the Thin Man in "The Passionate Palooka," from July 6,

1948

|

Muhammad's Real War: Understanding

the Events Leading to Ali's Draft Refusal

By Cliff

Endicott

Most of the people that I can find to discuss boxing with have almost unilateral respect

for Muhammad Ali, but surprisingly there are still some that consider him a coward or a

borderline traitor for his refusal to join the Army when he was drafted in 1967. Everyone

knows his official reason for refusing to serve: that he was a minister of the Muslim

faith and thereby exempt from military service. However, I think there were far more

involved reasons, and that these additional reasons were what had initially led him to the

Muslim. Furthermore, they explain much of his behavior, which is often very negatively

perceived, throughout his first reign as heavyweight champion.

"MUHAMMAD ALI" IS BORN

In 1960, Cassius Clay won an Olympic gold medal in boxing, in

the light-heavyweight division. He seemed to be on his way to great fame and success, and

he seemed as money hungry and eager as most fighters. He was generally accepted as a good

kid that was chasing the American dream. But growing up in Louisville, Kentucky, Clay had

been exposed to a great deal of segregation and racism, and beneath the grinning,

showboating surface, the young man was reaching a boiling point. His first documented act

of revolution was a relatively minor one, involving only himself. He was refused service

at a restaurant because of his color, and he reached a decision: He was no longer

interested in being a representative of a nation where he was not considered an equal.

Obviously there had to have been many similar events for him to reach that conclusion that

day, but this is the one that is documented to have forced his hand. His gold medal found

its way to the bottom of the Ohio River that afternoon, and Muhammad Ali was born -- not

in name, but in spirit. Ali's discovery of the Nation of Islam in the following months was

simply a progression from that point.

Cassius Clay continued to play the public-relations game with great enthusiasm, but he had

already begun becoming a radical thinker with a focus on civil reform. He continued to

fight his way up the rankings and won the heavyweight title. After taking that title in

1964, he finally made a public announcement that he had converted to Islam, was a member

of the Nation of Islam, and had been given the name Muhammad Ali by which he now wished to

be known. This was by no means a new aspect to Ali's life -- he had been attending Nation

of Islam meetings for more than two years. But he had never made that public knowledge,

fearing backlash from the media and the public. His close friend Howard Bingham has said

that many times before Ali's religion became public knowledge, he had witnessed Ali

carefully checking to ensure that nobody had recognized him before entering a mosque to

pray. But when he became open about his religion, even he would be shocked by the extent

to which he was maligned.

THE NATION OF ISLAM: PERCEPTIONS

White America -- and much of Black America -- saw the

Nation of Islam almost as a terrorist organization. It taught its members to hate the

white race and to believe that they were devils not to be associated with unless

absolutely unavoidable. It taught that any time a black man was wronged or threatened by a

white man, it was the duty of the black man to ensure it would never happen again. Today

this seems like an almost comically radical view; at that time, especially in the Southern

states, minorities could not easily be blamed for having such ideas. For over 300 years

there had been African-Americans, for well over 100 years all had been deemed "free men,"

yet it was not uncommon to see black men harassed, assaulted, or even murdered for nothing

more than being black. Segregation was still in full effect, especially in states such as

Kentucky, where Ali had grown up, with blacks forced to sit at the back of busses, where

they were not allowed to eat at most lunch counters and restaurants, and often had to find

public restrooms that had been designated "colored only." Growing up in such an

environment, it's not difficult to see how Ali could agree with a "white men are devils"

philosophy. The white men were, after all, the ones who had developed this completely

segregated society, despite their claims of all men being free and equal.

The Nation of Islam further taught that white men had designed society this way to ensure

that black people remained uneducated and impoverished, to prevent them from attaining any

real social or political power. This would create a lack of organization among

African-American communities and prevent them from revolting against the white power

structure. While this seems absurd on the surface, there's a great deal of evidence to

show that it's true, though not directly intended as the Nation implied. Without setting

about the task, rather letting it naturally happen through the conduct of a racist

political structure, black people were held back from social standing and education in

much the way the Nation of Islam suggested. The only real difference was that the Nation

saw it as a deliberate agenda; in reality it was simply the natural progression of an

all-white, largely bigoted political system.

Despite this, the popular view was that Ali had embraced a terror organization, and white

society (which included virtually all media and politicians) felt betrayed that Ali would

view them in such a way, particularly when he had achieved so much within the confines of

this same society. Popular opinion among whites, as reflected in the media of the day, was

that Ali should be viewed as an ungrateful, angry radical. He had taken what they had to

give him and then rejected the notion that he owed them anything. Ali's opinion seems to

have been that he had achieved everything he had through his own actions and abilities,

and truly owed nothing to the society that had provided the opportunities. Both arguments

have some weight, though neither is entirely accurate. But neither Ali nor white society

would accept even a fragment of the other's point of view.

Despite this, the popular view was that Ali had embraced a terror organization, and white

society (which included virtually all media and politicians) felt betrayed that Ali would

view them in such a way, particularly when he had achieved so much within the confines of

this same society. Popular opinion among whites, as reflected in the media of the day, was

that Ali should be viewed as an ungrateful, angry radical. He had taken what they had to

give him and then rejected the notion that he owed them anything. Ali's opinion seems to

have been that he had achieved everything he had through his own actions and abilities,

and truly owed nothing to the society that had provided the opportunities. Both arguments

have some weight, though neither is entirely accurate. But neither Ali nor white society

would accept even a fragment of the other's point of view.

Soon after winning the title, Ali went on a tour of Africa, where I'm sure his convictions

in the teachings of the Nation of Islam were strongly reinforced. For the first time, he

saw populations of virtually 100% black people that ran the power structures and who did

all of the high-tech and challenging work in their society. In America, Ali would never

have been exposed to this, and he likely never believed it was possible. Most people will

easily agree with a theory but are often unable to comprehend such a radical idea without

witnessing it firsthand. In Africa, the Nation of Islam's concept of a black-oriented and

-controlled social structure was the norm. Ali would have certainly begun to more fully

understand the Nation's belief that, left to their own devices, black people would be a

success and not have to deal with the sub-standard notion of themselves implanted by

growing up in a white-controlled society. It was probably then that Ali truly understood

that it was the white power structure in America that was keeping African-Americans from

realizing more than a small fraction of their potential.

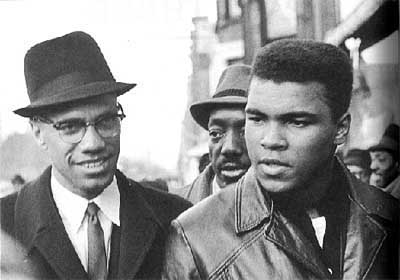

At around this time, Malcolm X would often describe the difference between the "house

negro" and the "field negro" in his public speeches. A "house negro" (which he considered

the majority of African-Americans to be) would complacently sit by and allow himself to be

directed by the dictates of white society. A "field negro" actually realized that he was

being wronged, and would militantly strike back to achieve the same freedoms as everyone

else. Ali was quickly becoming what Malcolm described as a "field negro." And really, with

the benefit of years of removal from the situation in analyzing it today, it would be

difficult to blame him for developing such a radical view. Ali was still quite young and

impressionable, and throughout his entire life, he had been forced to accept that there

was a fundamental difference between himself and whites simply due to his skin color. Then

along came the Nation of Islam, enforcing the idea that he was not only as good as white,

he was better. Since he'd had no hand in creating this bigoted society, he simply must be

better. Ali enthusiastically grabbed the idea with both hands, and I cannot realistically

fault him for embracing this belief. Everyone wants to feel that kind of warmth and need,

and the Nation of Islam provided that feeling to Muhammad Ali.

Malcolm X and Ali had been close during the months immediately prior to Ali's winning the

title, but a rift had developed between Malcolm and Elijah Muhammad, the Nation of Islam

leader. In keeping with his devotion to Elijah, Ali stopped keeping Malcolm's company.

Between winning the heavyweight championship and having his first defense, Malcolm was

assassinated. This possibly forced Ali to divide himself from the white social structure.

Malcolm X's only (recent) sin had been to educate Black America in understanding they did

not simply have to deal with racism, that they could and should force America to respect

their equality. When a man was murdered who had devoted his life to carrying this message,

Ali likely saw that the mantle must be carried on. In a very short time he would,

deliberately or accidentally, find himself to doing just that.

ALI THE VILLAIN

Ali's second defense of the heavyweight title displayed with precision the

popular attitude toward him and his politics. His opponent was Floyd Patterson, who was

perceived as a humble, nice guy by white America. This perception was due to Floyd's

obvious acceptance of society as it stood, finding his own place within it and not rocking

the boat. In the vernacular of the day, Floyd was a "good nigger." Patterson injected that

fight with all manor of rancorous overtones when he initially offered to fight for free,

saying he wanted the heavyweight title returned to all of America, not just the Black

Muslims. He also continued to call Ali by the name of Cassius Clay, which infuriated Ali.

Just before the fight Ali rhymed:

"Gonna put him flat on his back so he'll start acting black. 'Cause when he was champ he

didn't do as he should, he tried to force himself into a white neighborhood."

Ali was unable to understand how another black man, who had been subjected to the same

injustices and inequalities as he had, could possibly side with white America against

himself. This viewpoint of America was painfully evident after their fight, in which Ali

had obviously carried Patterson to prolong his punishment. Life magazine called the

fight "A sickening spectacle in the ring," while The New York Times compared

watching the fight to seeing a little boy pulling the wings off a butterfly. It's fair to

say that America, through the efforts of the popular media, had done everything possible

to make Ali a villain, which forced an even bigger wedge between him, themselves and the

public. A showdown was almost inevitable by that time, and if it hadn't been the draft it

would undoubtedly have been something else.

ALI VS. THE U.S. GOVERNMENT

In late 1965 Bob Arum was able to set a fight between Ali and

Ernie Terrell in Chicago for early 1966. Both fighters began training, and then the big

bombshell hit. Ali had earlier been classified 1-Y in the draft, as he had failed the

Army's intelligence tests due to his poor reading. The U.S. government had meanwhile

decided that they needed more soldiers for the war in Vietnam, and they changed the

restrictions; Ali (along with thousands of others) had their classification changed from

1-Y to 1-A. Those Americans whose classifications were changed were not informed of the

change until their draft cards arrived. Ali was an exception. At his training camp,

reporters arrived to inform him that he was now considered prime for the draft, and to

interview him on his views of this change. Ali, without any direction from his camp or the

Nation of Islam, allowed the interviews to occur. It was then that he made the infamous

statements, "I ain't got nothin' against them Viet Cong," and, "No Viet Cong ever called

me a nigger."

This all made national news, and the media again placed incredibly negative labels on Ali.

This time he was a coward who was afraid to die, a religious phony, and a draft dodger.

Ali had not even been drafted yet, but the media was already calling him a draft dodger.

The unfairness of this is evident when reflecting upon it, but at the time it was

considered a reasonable argument. Ali was simply telling America that his true enemies

were at home, and there was no need for him to travel to Asia to fight for his freedom. As

a result of those interviews and the media backlash, the Illinois State Athletic

Commission demanded an apology from Ali for making such unpatriotic remarks before they

would allow the Terrell fight to be held. Ali took the stance that the situation had

nothing to do with any athletic commission, and that he would discuss it only with the

government. For his refusal to apologize, Chicago canceled the Terrell fight.

For months, Ali could not stage a fight in America, as no athletic commissions would allow

it. Instead, he fought in Canada and Europe, where he was still welcomed and well-liked.

This argument was between Ali and the U.S. government, not the government of any other

nation, so it was no surprise that he was extremely welcome and well-received, especially

in Europe.

For months, Ali could not stage a fight in America, as no athletic commissions would allow

it. Instead, he fought in Canada and Europe, where he was still welcomed and well-liked.

This argument was between Ali and the U.S. government, not the government of any other

nation, so it was no surprise that he was extremely welcome and well-received, especially

in Europe.

When Arum was finally able to set another fight in America (after the storm had eased a

little), it would be in Houston in late 1966 against Cleveland Williams. Ali dispatched

him easily. The next fight was again scheduled for Houston, this time against Ernie

Terrell. Like Floyd Patterson, Terrell insisted on calling Ali by the name of Cassius

Clay, and to top Patterson, Terrell also called Muhammad a religious phony and a draft

dodger. Once again, Ali could not understand why another African-American would side with

white attitudes against him, and he made certain that Terrell understood that he

considered him a sellout and an Uncle Tom. The fight itself was similar to the Patterson

fight, with Ali not trying to knock Terrell out, just punishing him to the point of

knockout for much of the fight. The media again lambasted Ali for such a cruel and

intentional torturing of another human being, and pursued the "religious phony" label by

claiming Ali could not possibly be a considered a conscientious objector when willing to

conduct himself in such a way in the ring.

The inevitable showdown occurred when Ali received his draft card in March 1967 and

refused to be inducted the following month. The boxing commissions were poised, and less

than 24 hours after Ali refused to be inducted, his boxing licenses were revoked in every

state, and the New York State Athletic Commission and the World Boxing Association

stripped him of the heavyweight title.

PRINCIPLES, NOT THE EASY WAY OUT

What is often misunderstood is that Ali had already been informed

of what his military service would consist of. He wouldn't be in any trenches, hiking the

jungle, or forced to shoot the enemy. Much like Joe Louis in WWII, his tour of duty would

consist of boxing exhibitions and public-relations duties. He would have been encouraged

to defend the heavyweight title, all to promote the war effort. Ali knew this but still

refused, as his religion did not allow him to support the war in any way. Ali was harshly

criticized by black "statesmen" like Joe Louis and Jackie Robinson, who made it clear that

they believed that Ali should be grateful for the opportunities he'd had in America, and

fight to defend the nation that provided those opportunities to him. They fully believed

that Ali "owed" it to America.

Ali, while understanding this concept, was considerably more farsighted; he'd received his

opportunities because of exceptional abilities that most people did not have. Because most

people didn't have said abilities, they would never have the same opportunities for

success. He could not even consider defending a nation in which he would be treated as

subhuman had he not been blessed as an athlete. Furthermore, when Ali's conviction for

draft evasion finally came, the jury that convicted him consisted of 12 whites. Ali,

rightfully, did not believe that this jury should have heard his case, as a jury is

supposed to be of a man's peers. Certainly no white man could fully understand what it was

like to be a black man in America in the 1960s. Ali was also at that time being monitored

by the FBI, despite having conducted absolutely no illegal activity outside of the draft

issue. White America obviously was going to make an example of him. This effort further

split Ali from mainstream America, as he knew that had he been white, no such efforts

would have been made.

Today many believe that Ali was associated with the hippies and radical anti-war groups

during his exile. However, that is inaccurate, as Ali himself said in 1968:

"I'm not burning any draft cards, I still have it. I'm not lying on the Pentagon steps.

I'm not burning American flags. I'm only following the law. I'm going to fight it legally,

if I lose I'm just going to jail."

Perhaps the most clear words he ever spoke regarding his stand were in 1969, after being

baited by a member of the press who told Ali that he owed it to America to fight its

enemies; this same reporter then posed the question of whether Ali was simply afraid to

die. Ali replied, "If I'm gonna die I'm gonna die right here, fighting you. You're my

enemy. My enemies are white people, not the Viet Cong. You're my opposer when I want

freedom. You're my opposer when I want equality. You're my opposer when I want justice.

You won't even stand up for me in America for my religious beliefs, and you want me to go

somewhere and fight for you, but you won't even stand up for me here at home. I'm standing

up for what I believe in right now. You go fight if that's what you believe in."

The strength of Ali's convictions is obvious, as he turned down a cushy Army tour and lost

everything he had because of that refusal. His income, his savings (which went to legal

fees) and most of his freedom were taken away much the way his title was unjustly

stripped. He was broke, though not destitute, and could not work at his chosen profession

to make money. When Bob Arum set up a fight in Mexico for Ali, the government found out

and took Ali's passport to prevent it. The government was deliberately making sure Ali was

made as defenseless as possible. Every word Ali had ever claimed about the white-based

power structure was proving true -- simply because he refused to be pigeon-holed as a good

black boy who respected and adhered to his lower place in society, the power structures

were punishing him to the fullest extent of their abilities. The media had made Ali such a

complete villain that he couldn't even get work doing commercials. Sonny Liston, convicted

of armed robbery and assault with intent to kill earlier in his life, was doing several

high-profile commercials per year. Ali, who had become a minister and filed to be a

conscientious objector, was viewed as a less marketable commodity and no one would hire

him for endorsements. This is what Ali willingly subjected himself to simply by standing

up for his moral and religious beliefs.

CONFLICTS THAT ALI'S BELIEFS CAUSED

So what point am I trying to make? Muhammad Ali discovered

himself through the Muslim religion and the Nation of Islam's teachings and direction. For

a young man trying to find his place in the world, that is as strong a bond as he could

develop with anyone or anything. On the TV program Firing Line, Ali said that

several people had told him that he should be a leader in the Nation of Islam rather than

a follower. His reply at the thought of not being a follower of Elijah Muhammad was:

"Everything I got came from him. He taught me who I was, he made me proud, he made me

fearless and he made me love my own."

When the show's host suggested that Elijah was falsely teaching him that white people were

his enemy, Ali replied, "He doesn't teach us that you're our enemy. You taught us that

you're our enemy. Ask any black man and he'll tell you he sees it every day." Ali's belief

that he should not be forced to defend a nation where he was deliberately held back,

forced to accept inequality, and refused a fair place in society simply due to his skin

color was as all encompassing as his "official" stance that he would not serve because his

religion forbade it.

The official stance of being a Muslim minister is what most people recognize as Ali's

reason for not going to Vietnam. That is true, but his reasoning obviously went

considerably deeper than that. If he had gone to Vietnam, he would be defending a country

where he was considered subhuman, and he didn't believe that, had he gone to Vietnam, he

would be defending anything that was worth defending. Blacks had no reason to fight for

America, as America didn't respect them. America was a place where they could ride the

bus, but only in the colored section. America was a place where, if they were hungry and

stopped at a restaurant, they had to check for signs that said "No coloreds allowed"

before entering. If they needed to use the bathroom, they had to be sure that it was a

colored bathroom, as most public restrooms in the south were designated as "white only" or

"black only."

The official stance of being a Muslim minister is what most people recognize as Ali's

reason for not going to Vietnam. That is true, but his reasoning obviously went

considerably deeper than that. If he had gone to Vietnam, he would be defending a country

where he was considered subhuman, and he didn't believe that, had he gone to Vietnam, he

would be defending anything that was worth defending. Blacks had no reason to fight for

America, as America didn't respect them. America was a place where they could ride the

bus, but only in the colored section. America was a place where, if they were hungry and

stopped at a restaurant, they had to check for signs that said "No coloreds allowed"

before entering. If they needed to use the bathroom, they had to be sure that it was a

colored bathroom, as most public restrooms in the south were designated as "white only" or

"black only."

This reached so far up through society that the Pentagon, which had been built only 20

years earlier, contained twice as many bathrooms as required in order to have white and

colored restrooms. America was a place where Ali, as a black man, was considered little

more than an intelligent animal by a large portion of society, and was fiercely hated by a

small, radically racist portion. America was a place where he could be lynched because of

the color of his skin. America was willing to deprive him of his right to make a living

simply due to his refusal to obey their every whim, despite his following of their legal

precedents to the very letter.

In short, America of the '60s was not worth fighting for to

Muhammad Ali, while his religious beliefs were. Whether or not you agreed with him, he had

a very strong argument that could not be dismissed without downright ignorance of the

facts. America was assassinating black leaders for the sin of teaching blacks to refuse to

be content with having no place at the white man's table, and Ali is truly lucky to never

have had any serious attempts on his life. He was and is a hero to the idea of racial

equality, and he suffered more than any other single person who refused to go to Vietnam

for his refusal. The fact that he was able to eventually achieve great heights again is

notwithstanding to this argument, as only an athlete as great as Ali could have recovered

to the extent that he did. 1960s America treated him like an "uppity nigger" and proved to

him daily that it was not remotely worth his life or any other African-American's life to

defend. And honestly, based on the experiences of Ali's life to that point, can you really

blame him?

Contact Cliff Endicott at

editors@cyberboxingzone.com.

> contents

<

|