Comment on this issue Comment on this issue

Contact Us Contact Us

|

The Autobiography of Buddy Baer

By Buddy Baer and Vicki Baer

Note: This book has not yet found a publisher! If you can somehow help, please send an email and it will be forwarded to the person in charge. There is a printer-friendly version of the document here.

Copyright © Joseph Brumbelow

-1-

A Crown Misplaced

It is spring, 1984, forty-three years after the event that foreshadowed the end of my boxing

career, and I have not changed my mind. I should have been the second of the

brothers Baer to have won the heavyweight championship of the world. I say this

with due humility, for I have never claimed to be one of the all-time great

boxers. And I do think that my opponent on that fateful night of May 23, 1941,

Joe Louis, was probably the best of all heavyweights up to that time and even up

to now. But the facts are clear. In that particular fight I should have been

declared the technical winner on a foul. In truth, it was a double foul. Such a

decision would have given me the championship, and I think I would have held it

longer than my brother Max did.

It was the first of my two fights with Joe. The place was Griffith

Stadium in Washington, D.C., better known as the home of the Washington Senators

baseball team, which seldom drew the kind of crowd we had that night. The papers

said more than 30,000 were on hand. That was close to capacity. And I could feel

in my bones that at least half of those fans were pulling for me to upset the

champion. I was a 10 to 1 betting underdog, but judging from the roar that came

from those 30,000 throats when we entered the ring, I knew that the betting odds

(10-1 Louis) did not reflect the crowd's belief in my ability to win. After all,

I had won 49 of my 53 previous fights, and just six weeks earlier I had knocked

out "Beer Barrel" Tony Galento, the most famous fistic brawler of the time. On

top of that, I outweighed Joe by 32 pounds and had a six-inch reach advantage.

In short, I had the necessary physical equipment and a good enough fighting

record to justify the crowd's hope that I could destroy the legend of

invincibility that had grown up around Joe Louis Barrows. In my own mind, I knew

I could do it, just as Max Schmeling had done four years earlier.

No fighter

ever approaches the ring alone. When I came down the aisle in Griffith Stadium,

I was accompanied by Ancil Hoffman, my manager, Izzy Klein, my trainer, and Ray

Arcel, my cut man. It was a long walk. Each step we took seemed to generate

ever-higher decibel counts of noise from the sea of faces around us. When I

crawled through the ropes and began my warm-up dance in my corner of the ring,

the din actually hurt my ears. Ancil and Izzy shouted instructions, but I

couldn't hear them. Their lips moved furiously but soundlessly. Then Joe and his

entourage made their entrance, and a fresh wave of acoustical uproar rolled

across the playing field, engulfing the arena in which we would momentarily

perform. (Years later I would be reminded of this scene when I played the role

of a gladiator in the movie, Quo Vadis, which seemed to be a replay of the real

thing. Joe Louis was just as fearsome as any lion, and the fight crowd was just

as bloodthirsty as the mobs in ancient Roman amphitheaters.) Now Joe was in his

corner, doing his own little warm-up by jogging in place, staring past me and

seemingly into space. I thought about my battle plan, which was to attack,

attack, attack... Use my weight and reach to force Joe backward, into the ropes,

into the corners...Don't let him get set, or I get hurt... Respect his lethal

power, fight close in, move out of range fast, move back close, tie him up, hit

on the break.

The bell rang. We met in center ring. Joe immediately grazed my

chin with a left jab and I countered with five or six rights and lefts to his

body. He backed away, jabbing constantly with his left. I pursued him with two

swings that missed. He tried to catch me off balance and missed with his first

right of the fight. I nailed him on his neck with a left hook before he regained

his balance, and he then let loose a combination of lefts and rights to my head

that produced a fleeting vision of shooting stars and roman candles. But my head

cleared almost instantly and I moved forward again, throwing more leather than I

can remember in detail. Joe had his back against the ropes when I caught him

high on his cheekbone with my best-left hook, smashing his body between the two

upper strands of rope. He somersaulted out of the ring, striking the apron with

his head. To me, being out of the ring was the same as being down, so I returned

to my corner and watched Joe get up and step toward the crowd. He was dazed

enough to be turned completely around. One more step and he would have landed in

the press section five or more feet below, and, unlike Dempsey when Firpo

actually propelled him into the press row and he was pushed by the reporters

back into the ring, Joe might not have negotiated that maneuver in time. But he

caught himself before the fatal step, turned, and crawled back through the ropes

at the count of four. My memory is vague on when Arthur Donovan, the referee,

actually started the count, but I have since thought that he must have been very

slow. Is it really possible to be slammed through the ropes, land on your head,

rise to your feet and take two steps away from the ring, turn around and crawl

back, all in just four seconds? I have always questioned Mr. Donovan's count,

but this is the first time I have put it in writing. In any case, later events

pushed this matter into oblivion as a technicality not worth consideration. "So

what if Joe really used nine counts to get back, he got back in time, didn't

he?" was the general consensus. I agree with the consensus, but the technicality

just added to my doubts about Mr. Donovan later on. I tried and unfortunately

failed to put Joe away when fighting resumed. Before the round ended he

delivered a ferocious wallop to my rib cage, and I could see in his eyes that he

had regained his composure and fighting intensity. I thought to myself, though,

that I had taken some of his best shots and I still felt clearheaded and strong.

My battle plan still seemed sound. The second round was another story. Joe broke

through my defense time after time with short, quick blows that forced me

backward. It was just the opposite of what I wanted to do. I managed to counter

with a few punches that I knew were not effective. Joe's punches hurt, but so

far they weren't living up to his reputation as a killer. He won the round,

easily, and we were even on that score.

Round three was much the same as the

second, but in the fourth I landed a solid right on Joe's mouth that snapped his

head back and brought a quick look of alarm to his eyes. I tried to follow

through, but he deftly sidestepped my right and blocked my left jabs. Soon he

was on the attack, delivering painful smashes to my head and body. Score now, I

realized, was three rounds to one in favor of Joe, but I was still strong and

confident that I could knock him out if only I could reach his chin with a fully

powered right. One of the most frequent questions I have been asked since I left

the fight game is, "what do your seconds say to you between rounds when you are

losing on points?" Izzy told me after the fourth round of this fight to "stay

away! Force him!" A neat trick, to go backward and forward at the same time. But

I knew what he meant. I should do a better job of ducking and evading, then step

forward and blast away. In the fifth it worked to an extent. Joe threw a right

hand that cut a path through my hair as I got under it, then I came up with a

left hook to his left eye that clearly hurt him. He dabbed at the eye with his

glove and saw blood. "Is this really happening to me?" he seemed to say to

himself. In just a few seconds the eye began to swell and turn red. Though I

didn't really have the stomach for it, I tried to follow the boxer's credo that

an injury should be the target. Joe proved again that he could be very elusive,

and I could not take advantage of his difficulty. However, I thought the round

was pretty even. Not so the sixth. Joe came out firing, which surprised me, for

I thought he would be too tired to do that after hitting me with so many

punches, and missing with so many too, in the five previous rounds. Looking

back, I am convinced that he had become worried about my punching power. He was

afraid that he just might catch a knockout blow if he didn't finish the fight

soon. He rushed out and immediately rained a series of hooks and uppercuts to my

head, arms and body. Maybe it was the adrenaline that moved him to such fury,

but he was throwing harder punches now than in the beginning. A lightning right

caught my chin. I started to go down. Stories the next day said that I twisted

downward like a leaf from a tree, which was an accurate description of my

sensation of falling. Instinct guided me. When I settled on the canvas, stomach

down, I managed to get my knees under me and rise to be greeted again with a

volley of blows. This time I landed on my back, and took as much time as I

could. At the count of nine I was up, and flicked a weak left jab as Joe swarmed

all over me at the bell. I turned and walked toward my corner, reeling slightly.

When things are going badly it's funny how much can flash through your mind in a

couple of seconds. At this moment I was thinking of cold water splashing over my

head and shoulders when I reached my corner. That and a one-minute rest would be

enough to put me back in shape for the seventh round. Suddenly, the lights

almost went out. I found myself back on the canvas, rolling over and trying to

crawl to my feet. I had been hit, from behind, by the strongest blow of the

fight. I saw two of everything the lights above, the ring posts, Ancil, Izzy,

Donovan, Joe. Faces in the crowd gyrated dizzily. I almost threw up, but

instead, somehow, I got up. Griffith Stadium was in a wild uproar. Dozens of

reporters were on their feet screaming, "foul.' foul!" Ancil and Izzy were all

over Donovan, claiming the obvious, that I had been hit after the bell. Donovan

was pushing them back to the corner. The bell rang for round seven and I started

to move out, but was pulled back by Ancil and Izzy. They shouted at Donovan that

I should have extra time because of the late hit, but Donovan refused, and Joe

came out to fight. When my corner continued to hold me back, Donovan walked over

to Louis, raised his am, and declared him the winner. Now, I do not relish

winning a fight on a foul. But there are rules. Joe broke two of them when he

unloaded on me after the bell, and when his blow landed at the back of my left

ear a rabbit punch. Either one should have disqualified him, but Donovan chose

instead to disqualify me, on grounds that my handlers would not let me start the

seventh round. It was true; they wouldn't, unless I had time to recover from the

fouls. The rules plainly state that if the foul is not in itself considered to

be disqualifying, the victim is to have five extra minutes to recover from its

effects. If I had done the same thing to Joe, I would have expected to either

lose the fight then and there, or to see him granted the five-minute recovery

period. Maybe Joe didn't hear the bell. I'll allow him that. I'll also grant

that any fighter, when he senses imminent victory and in the excitement of the

moment, can lose his judgment enough to deliver an illegal punch. Joe did just

that, but I blame him for the outcome a lot less than I blame the officials for

failing to do their duty. By ignoring a flagrant violation of the rules, they

failed to protect me, failed to protect the sport of boxing, and failed to

protect the right of boxing fans to see a fair fight. One of the two judges did

try to do his job. Jimmy Sullivan voted to disqualify Louis for hitting after

the bell, and he hotly maintained his position during the next several days of

controversy over the decision. But he was outnumbered by the combination of the

second judge and Donovan, the referee. Later, I learned from Sec Taylor, a

sports writer for the Des Moines Register, that Donovan was on the payroll of

Mike Jacobs, who promoted most of Louis' fights, and that Jacobs owned 10

percent of Louis. He was sitting next to Jacobs when I belted Louis out of the

ring. According to Taylor, Jacobs' upper denture fell from his mouth, and he

shouted loud enough for many around him to hear, "there goes my meal ticket!"

Another aspect of Jacobs' operation that always bothered me was the use of

Donovan as the referee in all 24 of Louis' last fights, including 19 title

defenses. Donovan was not the only qualified referee in the country. There were

many others. The fact that Jacobs always chose Donovan tends to support my

belief that Jacobs thought he could depend on Donovan in a close situation. In

my case that certainly proved to be true. But Louis, of all fighters, did not

need that kind of insurance. Even so, it looks to me as though Jacobs decided

not to take any chances. I don't know if there was a law at the time prohibiting

a promoter from owning a piece of a fighter in bouts he was promoting. I don't

know if there was a law that prohibited referees from being on the promoter's

payroll. But I do know that it wasn't ethical. I have said many times since my

boxing career ended that fight promoters and financiers usually have only two

things in mind, petty and grand larceny. I'll agree that my brother, Max, who

heard that fight on the radio at his home in Sacramento, was not an objective

interpreter of what happened, but I like what he said to reporters that night.

"I can't understand why a fighter has to go into the ring, fight Louis, the two

judges, the referee and the announcer. Buddy got the works. This is the first

time I heard of a champion getting his eye cut and having it affect his

hearing." He said it better then than I can now. As I said at the beginning, I

think that if I had been awarded the title (just as Schmeling had been when he

was fouled by Jack Sharkey), I would have held it longer than did my brother

Max. He loved high living more than he loved boxing. He had the talent to have

been as good as or even better than any other heavyweight in history, but he

frittered away his opportunities on a diet of fast night life, happy high jinks

and plain non-stop fun. Because I was younger and trying to follow in his

footsteps as a boxer, I would have benefited by his mistakes.

Copyright © 2002 Joseph Brumbelow

|

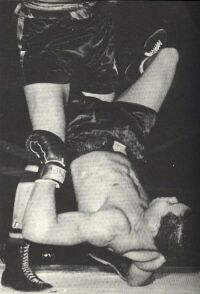

Buddy Baer floors Joe Louis in their first fight.

|

. . . THE CBZ JOURNAL

. . . THE CBZ JOURNAL . . . THE CBZ JOURNAL

. . . THE CBZ JOURNAL