| |||

| COMMENT | CONTACT | BACK ISSUES | CBZ MASTHEAD |

|

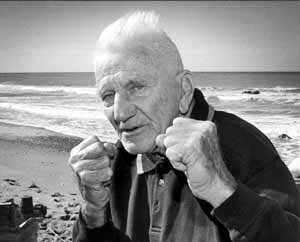

The Last Story: A Personal Tribute to Dick DunnBy Orion FooteI'll never forget Thursday, August 9. I had driven from Featherston to Wellington early that morning, and after dropping off my daughter at school, I was desperate for a caffeine fix. So I headed straight for La Bodega café on Willis St. I knew the coffee would be good, and I wanted to contemplate the day's business ahead of me. Upon entering the café, I was met with the sight of a familiar face from a few years ago, whom I hadn't seen for quite some time. The connection was fairly instantaneous, as it so often is with an old friend, and the dark, aromatic liquid soon fuelled our exchanges. While telling him about the recent formation of the Featherston Boxing Club, I happened to mention Dick Dunn, with whom I'd had the privilege of meeting the previous autumn, and who had left an indelible impression upon me, as the old wizard had done with countless others over the course of his 93 years. My friend's response was totally unexpected and quite chilling: "Oh, Dick Dunn, I remember him. He had the boxing club in the Hutt Valley. I just read the news in this morning's newspaper. I suppose you already know." I sat there in stunned silence, unable to say anything for what seemed like an eternity. Dick had heard the final bell two days prior, on August 7. I had in some way connected with my own father when I met Dick Dunn for the first time. My whole family had been ripped apart when I was only 18 months old. I was, along with nine other siblings, placed in a foster home with people whom, despite giving me as much love and support as they were capable of, I had always known weren't my real parents. Over the years I'd often wondered why I was so drawn to boxing. I vividly remember as a boy rushing home from school in the afternoons—due to the time difference in the Southern Hemisphere—to watch delayed screenings of the Greatest, Muhammad Ali, fight those epic battles with Joe Frazier, George Foreman, and Leon Spinks. During the 1980s it became Sugar Ray Leonard and Tommy Hearns, but the feeling never changed. As a teenager I was to learn that my real father, Ernest Foote, had fought as an amateur alongside his brother, Harold, at one of the many local boxing clubs in Wellington before enlisting with the 2nd Expeditionary Force at the outbreak of World War II in 1939. The game was good to Uncle Harold. He went on to win national titles as a bantamweight, and my father fought briefly as a flyweight before drifting away from boxing after the war. My only recollection of my father is of a meeting between us when I was about 6; we trudged around a fairground for what seemed like hours. I remember the endless walking and a brightly colored swirling candy stick. Later in the day he returned me to the only home I had ever known. I don't remember anything he said to me that day. Many years later, on a cold evening in 1998, I returned home from work to find a phone message. The frail voice on the other end simply said: "I'm Dick Dunn … I'd like to hear from you … I think I remember your father." Sitting in that downtown café, my mind flashed back to only a few days ago, when I had spent the morning talking to Dick (mostly listening!) as I had on numerous other mornings, listening to his spellbinding tales of his experiences as one of New Zealand's foremost sporting coaches, particularly in the boxing arena—colorful anecdotes about many a young fellow who had found courage and truth in slipping on a pair of boxing gloves and stepping through the ropes. For many of these young fellows, Dick had been so much more than just a coach; he had given purpose and meaning to their lives. He had been in the garden hunched over a few dry logs with a small axe, quietly absorbed in the task at hand, the sun glinting in his opaque mass of white hair. As always he seemed pleased to see me: "I've been looking for something to do," he said as the axe lodged itself with a hollow thud into one of the logs, not wanting to budge without a fight from its wielder. I had brought along a photo as a gift that I knew would be of considerable interest to him. It was of the 1912 New Zealand boxing team taken in Sydney at the Australasian Championships, which I had acquired recently from the son of George W. Barr, who won the featherweight title at the 1912 New Zealand Amateur championships, before being selected as the featherweight representative for the New Zealand team to compete at the then yearly Australasian tournament. Later, inside over a cup of tea, he gazed intently at the stoic faces of youthful spirit, assembled together before battle with their Australian counterparts. He turned to me, the all-knowing eyes that always seemed to make you want to listen, that would draw you into the story as if slipping back in time: "The game's greater than the individual," he said. "People will come and go, but boxing will always survive. It must survive; you'll remember all the things I've said long after I'm gone." The weary-though-steady hand raised his cup and he sat thoughtfully sipping his tea. I knew then that this particular visit was, inexplicably, of more significance than others, and his mood seemed somehow more pensive than usual. "Did I ever tell you the story of Ansell Bell?" he inquired, his eyes suddenly lighting up with enthusiasm. He had, on other occasions, told many stories before, although this particular one it seemed, he had been saving as a grand finale. What follows is, to the best of my recollection, an account of events that occurred over 35 years ago, brought back to life by Dick himself. I think it captures the essence of what was told to me that afternoon and indeed something of the essence of the man himself—for it must be said that no one could tell a story quite like Dick: It was during the 1966 Commonwealth Games in Jamaica when I took the New Zealand boxing team over there. On our first day we arrived at the gymnasium where we would all be training. I was getting the boys organized for our first training session. I told them all to put their valuables like watches, pocketbooks, and so on into a big bag that I had, and I would put it somewhere safe. I noticed that in a corner of the gym was a bed and a small cabinet. It seemed as though someone lived there. A curtain was pulled across to allow some privacy, but it seemed to be where someone actually lived; all they seemed to have was a bed and one or two possessions. As we were getting ready to begin our first session, an elderly, slightly dishevelled man appeared from behind the curtain and came over to us. He told us that he would take care of all our things and not to worry about it, that all of our belongings would be safe with him. When we had finished training, everything was there as we had left it. The same thing happened the next day; the fellow seemed pleased to be of some help to us and once again offered to take care of our belongings. One morning not long after that, I asked him his name. "I'm Ansell Bell," he replied, "I'll be staying here for a while." I thanked him for his help. I remember that night very clearly, as it was particularly hot and humid. I had trouble getting to sleep, and I had a strange feeling that the name Ansell Bell was familiar in some way. I lay there thinking about it for ages, and suddenly I remembered. When I was a young boy, I had kept a scrapbook full of photos and newspaper clippings about interesting people, mainly boxers and others sporting people. In a flash of recall, I remembered a cutting from my scrapbook about a fellow who had visited Australia as a young professional boxer and who had fought the great Australian lightweight Billy Grime sometime in the 1920s. His name was Ansell Bell. The next morning I asked him if he had been a boxer. "Yes I was," he said. "They took me to places all over the world to fight. I went to Australia for a while and fought over there. I even fought Billy Grime once, you know." I couldn't wait to tell all the boys about him. Some of the other boxers there at the gym would just ignore Ansell, they would treat him as though he was a crazy old man and wouldn't give him the time of day, but I introduced him to everyone in the gymnasium and told them what a great fighter this man had been in his day. Many of the boys took a liking to him, and they would leave fruit and things in his cupboard when he wasn't there. "You see, during our time at that gym, during the competition—because of the respect and friendship that we all gave to Ansell—he became a different man. Others who were training at the gymnasium, after being told who this man was would now speak to him, wanting to know all about his life as a young professional boxer. For those few weeks his sense of pride and dignity was renewed. One day at training I jumped into the ring to spar with Paul Domney (New Zealand's lightweight entry). I really wanted to get him in shape, and the sparring was pretty torrid. I don't know how old I was at the time, but I wasn't a young fellow anymore! When we'd finished sparring, the coach of the American boxing team who had been watching with boxers from all over the world shouted out: "Let's hear it for the New Zeeland coach!" When the competition started, we took him to the stadium where the boys were boxing and Ansell had the time of his life. I took him into our corner that night and we bought him rum and cokes at the bar. That night as we were getting ready to go back to camp, I told our manager that Ansell would be coming back on the bus with us. He replied that because Ansell wasn't part of the New Zealand team, he wouldn't be allowed on the bus, and he wasn't going to be convinced otherwise. I told him that if they wouldn't allow Ansell on the bus, then I would walk back to our quarters with him. Bill Kini, who had won the gold for New Zealand as a heavyweight that day heard all the fuss and stepped off the bus, and addressing the team manager, made it clear in no uncertain terms that if Ansell and Mr. Dunn were walking back, then so was he! The rest of the team began to file out of the bus one by one … well, you can guess the outcome. A couple of years later, a friend of mine was travelling to Jamaica and I asked him to find Ansell and give him a box of cigars that I'd gotten for him. Hut he couldn't seem to find him. Apparently he had passed away not too long ago. If you find Billy Grimes' record, you'll see his name there: Ansell Bell. He repeated the name quietly to himself, and for an instant a faint mist appeared in his eyes, as though he had become momentarily transported back in time to another day at Kingston in 1966. A calm silence followed, broken only by the occasional chirping of the birds on this crisp clear afternoon. The story had ended, though had found a new life and would live on. We walked outside into the afternoon sun and said goodbye for what would be the last time, and I thought of Ansell Bell and of the many other stories. Thanks, Dick. I won't forget. Many other people who won't forget and whose lives had been changed in some way turned out to pay their last respects in Masterton on a glorious afternoon in August. Dick had often said that he would never be alone after he'd gone, as he had made so many good friends in his lifetime. I'm proud to say that, if only for a short time, I was one of them. May you rest in peace, Dick. Note: Ansell Bell was a husky Negro featherweight who hailed from Panama. He was under contract to Stadiums Ltd and managed by Bob Laga in the early 1920s. After his first bout in Australia against "Curly" Wilshur, whom he despatched in sensational style in 16 rounds, he was hailed as the heaviest puncher seen in Australia since Eugene Criqui. He fought four professional contests in Australia in 1924, including a 20-round battle with Billy Grime on December 6. Grime held both Australian featherweight and lightweight titles during that year. |

|

|

| Upcoming Fights | Current Champions | Boxing Journal | CBZ Encyclopedia | News | Home |