. . . THE CBZ JOURNAL

. . . THE CBZ JOURNALTable of Contents

. . . THE CBZ JOURNAL

. . . THE CBZ JOURNAL |

May 2001 Table of Contents |

|

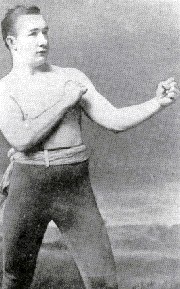

Jack McAuliffe ... "Quick As Greased Lightning" By Tracy Callis Jack McAuliffe boxed during the years when fighting was evolving from the use of bare knuckles to gloves. Bert Sugar (1982 p 31) wrote: "Jack McAuliffe was a lightweight superstar during the transitional period when boxing shifted from the bareknuckle era to adaptation of the Marquis of Queensberry rules." He was one of a handful of men who retired with an "official" unbeaten record. The others were Young Mitchell, Jimmy Barry, and Rocky Marciano. McAuliffe was a product of the "new school of pugilism" and an exponent of the more polished boxing style -- a heady, crafty, intelligent boxer who (like Gene Tunney years later) studied the every move, tactic, and tendency of his opponents. He was blessed with that wonderful, natural gift of extreme quickness, was light on his feet and employed springy, bouncy, brisk movements. Jack was an active puncher who not only boxed cleverly but slugged it out with stiff punches too. He was a master strategist, not a terribly crunching, power-hitter but possessed a wicked, sharply-driven, straight left jab that cut opponents up much like Ezzard Charles could do to his foes in more recent times. Mee (1997 p 236) called Jack "Quick-thinking, sharp-punching, and an expert ring general." Haldane (1967 p 168) described McAuliffe, "undoubtedly a sterling pugilist, who was not called the 'the Napoleon of the Ring' for nothing. He could fight as well as box and he was as hard and durable as any man of his time, for these were the days of two-ounce driving gloves." McAuliffe was born in Ireland and moved to Bangor, Maine in this country as a young child. He grew up in a rough neighborhood and learned to scrap there. After a few years, his family moved to Williamsburg, a hamlet of brooklyn, NY and, as a youth, he worked as a cooper. There, he met another young man who liked to box and became good friends with this fellow worker, who had a natural gift for the fistic game. His friend taught him many secrets about the sport. The name of this friend was Jack Dempsey, who went on to become one of the all-time greats of the ring as "the Nonpareil." What the "Nonpareil" taught McAuliffe was invaluable and Jack often had Dempsey in his corner iving him advice during fights. Fleischer (1944 p 35) wrote that Jack "always trusted the Nonpareil's good judgment and felt the odds to be in his favor whenever Dempsey was in his corner." Dempsey soon won the Lightweight Championship of America and, later, when he gave it up to fight at a heavier weight, he "named" McAuliffe as an outstanding claimant for the vacated title. This gesture gave credence to Jack's ability as a fighter and when he joined up with Billy Madden and toured the country, whipping many "comers", his claim of champion was enhanced. Jack then proceeded to challenge Jimmy Mitchell, a talented and popular pugilist of the time, to fight for the crown, and when Mitchell refused, many acknowledged McAuliffe as champion. Victories over Jack Hopper, Billy Frazier, and the Canadian champion, Harry Gilmore, solidified Jack's claim as Lightweight Champion. Johnston (1936 p 302) recorded that Jack "quickly demonstrated his right to the crown. He took on all the men in the class who challenged him and disposed of them all." As champion, he liked the high life, good food, and fine clothes. He also loved the race tracks and was addicted to gambling habits. McCallum (1975 pp 225 227) called him "the Dapper Dan of the ring" and "the Beau Brummel of the sports world". Accordingly, he did not take to training too well and never over trained. On a number of occasions he came in heavier than planned -- but he was such a talented fighter, it usually did not matter. During his career, McAuliffe beat such talented fighters as Joe Ellingsworth, Billy Ellingsworth, Jack Hopper (twice), Charles "Bull" McCarthy (twice), Billy Frazier (twice), Harry Gilmore, Billy Dacey, Paddy Smith, Jimmy Carroll (twice), Austin Gibbons, Billy Myer (twice), and Horace Leeds. He also gained a controversial win over Young Griffo (see below). In a nip-and-tuck battle with scrappy Harry Gilmore in January of 1887, McAuliffe knocked out the Canadian Champion in what many boxing veterans of that day called "the fiercest and most exciting fight they had ever seen between star lightweights" (see Fleischer 1944 p 34). While McAuliffe officially had an unbeaten record during his career, there were three fights in which he may not have been the better man. In November of 1887, at Revere, Massachusetts, he fought Jem Carney of England in a 74-round contest. Jack was the much better boxer but Jem was aggressive and rough. The fight turned into a war of dirty tactics with several knockdowns and plenty of blood, kneeing, and eye-gouging. Many feel that Carney was better in this fight and was proving to be stronger in the last few rounds that were fought. Jack appeared very tired when his supporters, tired of the questionable tactics by Carney, broke into the ring during the 74th round. The referee stopped the fight and promptly declared the fight a "draw" in a controversial decision. Johnston (1936 p 305) described the fight, "For sheer bulldog courage it has seldom been equaled anywhere. It was brutal, if you will, but no one can deny the pluck and courage of the two lightweight champions." In February of 1889, at North Judson, Indiana, against Billy Myer in their first bout, Jack broke a bone in an arm early in the contest but fought on. As the match continued, Jack's brilliance dimmed and Myer's stamina and tenacity began to catch up with the Champion. Johnston (1936 p 305) said Myer "had an unorthodox style, but he was a terrific puncher and could absorb a walloping." The fight ended in a draw after 64 hard fought rounds but from all accounts, Myer was better. Billy once said "I know that I could have whipped him that night at North Judson [even though] he might now knock me silly in five minutes" (see Chicago Tribune, Feb 16 1889). Jack later avenged himself in a second bout by knocking Myer out. Afterwards, in a third match, he convincingly whipped Billy again. When Young Griffo came to America, Jack met him in a ten-rounder in August of 1892 and came away with the official decision. However, Jack afterwards said "he'd been beaten in the Coney Island set-to" (see McCallum 1975 p 263). In 1890, McAuliffe took on Jimmy Carroll, who had backed George LaBlanche against the "Nonpareil" Jack Dempsey when LaBlanche used the "pivot blow" to beat the outstanding Champion. Being a close and loyal friend of Dempsey, McAuliffe took the fight in a very personal way and poured it on Carroll, finally knocking him out (see Johnston 1936 p 306). While working in the corner of the great John L. Sullivan at New Orleans against Jim Corbett in September of 1892, Sullivan told McAuliffe that everyone gets "his" sooner or later and advised Jack to retire before it happened to him. Jack wisely took his advice (see Johnston 1936 p 308). Mee (1997 p 236) wrote, "Jack McAuliffe was a great lightweight although historians argue over his rightful status simply because of the chaotic nature of the sport when he was claiming to be champion of the world." He added, "Nobody denies that McAuliffe was extraordinarily talented." Harry Gilmore, a great lightweight fighter of that day, Canadian Lightweight Champion, and "Professor of Boxing" in his Chicago school for many years once said, "To a greater degree than any other Lightweight Champion I have known, Jack McAuliffe outclassed the best men of his day." He went on to say, "On top of that, he was a lightning thinker, and as fine a general as ever performed between the ropes" (Fleischer 1944 p 6) Stillman (1920 p 73) wrote of McAuliffe, "One of the best lightweights that the division has ever held. A wonderful two-handed fighter, who depended particularly upon his straight blows." Jack Curley, boxing and wrestling promoter, called Jack a "great fighting machine" (The Ring, Jun 1926 p 13). Dewitt Van Court, long time Los Angeles boxing instructor and promoter, ranked him as the #3 All-Time Lightweight (1926 p 108). Haldane (1967 p 225) ranked McAuliffe along with Joe Gans, Benny Leonard, and Battling Nelson as the greatest lightweights who ever fought while Jimmy Johnston, President of the National Sports Alliance, named Jack as the #1 All-Time Lightweight (The Ring, May 1926 pp 12 13). Spider Kelly, oldtime trainer (The Ring, Oct 1924 p 14) said, "Jack McAuliffe was the best lightweight that ever lived. I've seen them all and boxed with Gans, Everhardt, Lavigne, Griffo, and many others, but to my way of thinking McAuliffe was far above any of them. He was as strong as a bull, clever, could hit like a middleweight, and had a great head on him." In an article in The Ring by Tom Ephrem (June 1939), Billy Myer, having seen all the lightweights up to that time, still rated "McAuliffe as the greatest of all lightweights, past or present." In the opinion of this writer, McAuliffe was the #6 All-Time Lightweight, perhaps a shade below the likes of Benny Leonard, Joe Gans, Roberto Duran, Henry Armstrong, and Aaron Pryor. "Napoleon Jack" is in a class with Packey McFarland, Barney Ross, Tony Canzoneri, and Pernell Whitaker. Not bad company! The following is a tribute to McAuliffe (from Fleischer 1944 p 1): Napoleon, war-master, was a terror to his foes, A general of generals, as everybody knows; And Jack McAuliffe, lightweight king, who many battles won, Was tagged by his admirers - "The Ring Napoleon!" It was a fitting sobriquet for one whose clever wits Were ever on the keen alert to back his fighting mitts, But, unlike Bonaparte the Great, our champion never knew The stigma of defeat, Jack didn't "meet his Waterloo!" Credits: A special thanks to Mark Dunn (of Bloomington, Illinois) for supplying pertinent data related to Jack McAuliffe. His tedious and thorough search of the Chicago (Il) Tribune, the Bloomington (Il) Bulletin and Daily, the Peoria (Il) Daily Transcript, Herald-Telegraph, and Journal, and the St. Louis (Mo) Post-Dispatch newspapers of the 1880s and 1890s is greatly appreciated. References Chicago Tribune. Feb 16 1889. "Myer Anxious to Fight" (contained in the Chicago Tribune, Feb 16 1889 issue) Curley, J. Jun 1926. "Tommy Ryan Greatest Fighter of All Time ..." (contained in The Ring, Jun 1926 pp 4, 5, 13). Ephrem, T. Jun 1939. "Billy Myer, The Streator Cyclone" (contained in The Ring magazine, Jun 1939 issue). The Ring Publishing Corp. Fleischer, N. 1944. Jack McAuliffe (The Napoleon of the Prize Ring). New York: The Ring Publishing Corp. Haldane, R.A. 1967. Champions and Challengers. London: Stanley Paul and Co. Johnston, A. 1936. Ten - And Out! New York: Ives Washburn, Publisher Johnston, J. May 1926. "Jimmy Johnston Names Greatest Fighters of All Time ..." (contained in The Ring, May 1926 pp 12, 13). Kelly, S. Oct 1924. "Greatest Fighters as Viewed by a Veteran" (contained in The Ring, Oct 1924 p 14). McCallum, J. 1975. The Encyclopedia of World Boxing Champions. Radnor, Pa: Chilton Book Company Mee, B. 1997. Boxing: Heroes & Champions. Edison, NJ: Chartwell Books, Inc. Sugar, B. 1982. 100 Years of Boxing. New York: Gallery Press Stillman, M. 1920. Great Fighters and Boxers. New York: Marshall Stillman Association. Van Court, D. 1926 The Making of Champions in California. Los Angeles: Premier Printing Company

|

Jack McAuliffe Tracy Callis Profiles Muhammad Ali Jim Corbett Jack Dempsey Nonpareil Jack Dempsey Bob Fitzsimmons Joe Frazier Larry Holmes Peter Jackson Jim Jeffries Jack Johnson Sam Langford Sonny Liston Joe Louis Rocky Marciano Kid McCoy Billy Miske Sailor Tom Sharkey John L. Sullivan Gene Tunney |

| Schedule | News | Current Champs | WAIL! | Encyclopedia | Links | Store | Home |