JUNE 2005

Poem of the Month

By Tom Smario

Cinderella Man

Book Excerpt by Mike DeLisa

Entertaining Fighters and Prospects

By Adam

Pollack

Fatty Langtry: Pudgy

Pugilist of the Past

By Robert Carson

John Klein: 19th-Century

Trainer

Extraordinaire

By Pete Ehrmann

Ring Leader

By Ron Lipton

Incentives in Professional

Boxing Contracts

By Rafael Tenorio

Fight Town

Book Excerpt by Tim Dahlberg

The Regulation of Boxing

on Tribal

Lands:

Towards a Pan-Indian

Boxing Commission

By James

Alexander

Spotlight on Cut Man Lenny DeJesus

By Sam

Gregory

Dick Wipperman

by Pete Ehrmann

Jack Johnson: The Dates,

the Events, the Sources

by Stuart Templeton

Touching Gloves with...

"Irish" Art Hafey

by

Dan Hanley

|

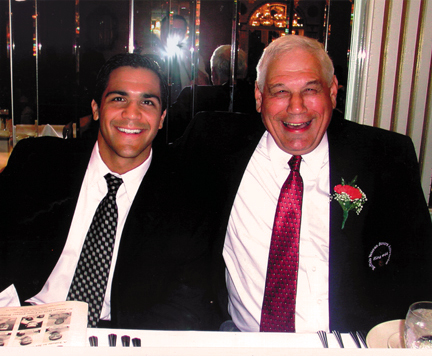

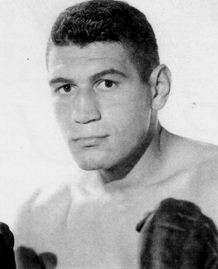

DICK WIPPERMAN

By Pete Ehrmann

Recounting in his autobiography the close call he had against Dick Wipperman, 1960s

British heavyweight champion and world-title challenger Henry Cooper referred to Wipperman

as an American "cowboy." Maybe that's because to Brits, all Americans are cowboys -- or

because Wipperman hails from the western-sounding eastern metropolis of Buffalo, New York.

Or, maybe it's because so many of the most notable fights in Wipperman's eccentric

eight-year career had a real Wild West quality to them.

A strong law-and-order man in 38 years as a patrolman with the police force in the Buffalo

suburb of Cheektowaga, in the '60s Wipperman was one of boxing's most volatile and loosest

cannons, whose career was summed up before his last fight by the newspaper headline:

"Turmoil! That's Boxer Wipperman's Stock in Trade."

Now 63 and mellowed by a life he says that has mixed "humor, sadness, and irony,"

Wipperman is more insightful than inciteful. He even goes so far as to say that some of

the most outrageous stories about him might be exaggerated or even untrue.

Like the one about when he fought Kid Savage in Zanesville, Ohio, in 1964. The Kid was a

deaf-mute who counted on the referee to signal him when each round was over. Only the ref

was a little tardy in doing so in the Wipperman fight, with the result that as Wipperman

turned to go to his corner at the end of one round, he was Savagely smote on his

unprotected chin and dropped to the canvas. He got up, according to one newspaper account,

and scored a double KO -- first flattening the referee, then Kid Savage.

While acknowledging that the referee did end up in extremis, "I didn't do it," maintains

the man whose grandchildren call him "Grandpa Bulldog."

But the fact is that Wipperman's arguments with referees and officials were sometimes more

strenuous and entertaining than the ones with the guys in the other corner.

The most famous of these almost started a riot at Madison Square Garden on October 2,

1964. Wipperman, who'd won 26 times against two losses and a draw since he beat Abdul

Hakeem in his first pro fight in 1961, had come up via the Don Elbaum tank-town circuit.

In contrast, his opponent that night as the beneficiary of a well-greased, high-powered

media campaign that made 6-foot-9, 240-pound James J. Beattie a rising star in boxing.

"Kid Galahad, Inc.," was the name of the syndicate comprised of New York businessmen and

PR mavens that settled on Beattie as its candidate to "help pull the fight game up by its

bootstraps" after a nationwide search via newspaper advertisements. Toward that end, the

camera-friendly Minnesotan had been carefully steered to a 12-1 record in a growing media

spotlight that even made Beattie the subject of a prime-time documentary on ABC-TV.

But Wipperman, 36 1/2pounds lighter and six inches shorter, not only easily outpointed

Beattie over the first six rounds of their scheduled eight-round semifinal to the George

Chuvalo-Doug Jones heavyweight elimination match, but had him bleeding so badly that the

ringside doctor visited the giant's corner at the end of the sixth round in what most

onlookers figured was a prelude to a big upset.

When the seventh started, Beattie came out swinging. The punches didn't land, but

Beattie's forward progress drove Wipperman to the ropes, where he covered up to wait out

the onslaught. But 46 seconds into the round, referee Barney Smith stopped the fight and

declared Beattie the winner.

"I was livid, pissed," says Wipperman. "I had busted Beattie up and banged him up pretty

good, and then the fight was stopped. I started yelling and screaming."

So did the crowd at the Garden, especially after Wipperman charged at Beattie and took a

swing at him. Then he tried to grab the ring microphone from the announcer to plead his

case to the customers until a police escort was needed to get Smith out of the ring as

pennies and peanuts showered down on him.

"The wild buffalo from Buffalo had a justifiable complaint," wrote the New York

World-Telegram's Lester Bromberg. But today's kinder, gentler Wipperman wishes it

hadn't happened: "The referee did what he thought was right. He was worried about me and

didn't want me to get hurt."

While the state boxing commission fined Wipperman $100 and suspended him for a month, the

Garden wasted no time in signing him up to oppose another young heavyweight getting a big

buildup. Oscar Bonavena had knocked out all six of his opponents, and on paper it looked

like a riveting match -- the crude slugger from Argentina versus the hotheaded New Yorker.

But the fight was so bad, with Bonavena easily winning a 10-round decision, that one

writer went so far as to suggest that Wipperman "decided to get $100 worth of

satisfaction" -- a reference to his fine for the Beattie incident -- "by stinking out the

joint."

"What happened to the tiger we had against Beattie?" wondered Garden President Harry

Markson as Wipperman ran away from Bonavena.

Two judges gave Oscar all 10 rounds; the other said Wipperman won two. Yet in his dressing

room after the fight, Wipperman railed against the decision. "I ask you, isn't boxing the

art of self-defense? I clearly outboxed him all the way and they gave him the decision.

What do I have to do to win points here in New York?"

Over 40 years later, Wipperman views matters differently. "I ran like a deer," he

concedes. "I got clobbered."

Two months after the Bonavena fight, Mr. Hyde reappeared when Wipperman went to London to

face Cooper. At the end of four rounds, Cooper's delicate features had been carved up so

brutally by Wipperman's left that had the fight been anyplace but on the British Empire

champion's home turf, it would've been stopped.

"The skin around one eye was flapping open and he was bleeding like a stuck pig,"

Wipperman recalls. But in the fifth round, a desperate Cooper unleashed his trademark left

hook and Wipperman hit the deck. He got up, and the debate that ensued between him and

referee Jack Hart would've done the Cambridge Union proud.

Hart: "I'm stopping the fight, chap, you're hurt."

Wipperman: "No shit. You're a super-genius. But let him knock me down again."

Hart: "Chap, I'm worried for you."

Wipperman: "Help me find my head somewhere down here, and I'll put it back on and he won't

come out for the next round, he's cut so bad."

Forensically, Wipperman had the upper hand. But the unmoved referee awarded the bout to

Cooper.

After four successive wins, the Garden brought Wipperman back to meet undefeated,

title-bound Joe Frazier. In his dressing room beforehand, Wipperman psyched himself up by

telling himself that his last name translated to "Whip-a-man," but in the ring the

whipping was administered by Smokin' Joe in five rounds.

By then, Wipperman was a full-time policeman in Cheektowaga, which put him in situations

even more dangerous than a boxing ring. One night while trying to apprehend a gang leader

who was resisting arrest, Wipperman accidentally shot and killed the man. A review board

cleared him of any wrongdoing, but the gang didn't see it that way and targeted Wipperman

for revenge.

Gang members made a run at him a couple times, but slunk away when Wipperman indicated

what he thought of them and their intentions by saying, "If you're going to come after me,

have some honor and at least take a shower first." And: "Don't you want to get some more

guys and even things up a little?"

It was the same attitude Wipperman took into his fights. When Alvin "Blue" Lewis promised

at a pre-fight press conference to "improve on the job Joe Frazier did" on Wipperman by

knocking him out in the third round, Wipperman drew laughs by answering drolly, "I'm still

going to show up for the fight."

It was the same attitude Wipperman took into his fights. When Alvin "Blue" Lewis promised

at a pre-fight press conference to "improve on the job Joe Frazier did" on Wipperman by

knocking him out in the third round, Wipperman drew laughs by answering drolly, "I'm still

going to show up for the fight."

After Wipperman lost the decision, Buffalo sportswriter Frank Wakefield wrote that if he

"had a punch half as big as his fighting heart, [Wipperman] would be in the midst of the

scramble today for the defrocked Cassius Clay's crown."

The journey finally ended after Wipperman dropped a decision to ranked Buster Mathis in

Milwaukee in 1967. After the fight, the 30-14-1 (14 KO's) loser and Mathis went out

together for a beer.

"No regrets," says Wipperman about his boxing career, although "it'd been nice if I got a

little more glory." A few years ago, he was pleasantly surprised when the Buffalo Veteran

Boxers Association inducted him into its Hall of Fame.

Divorced, Wipperman shares an apartment with his black poodle, "Bo Jackson." For a long

time he coached little-league football, and stressed to his young players that yelling and

screaming at the officials wasn't the way to go.

That might stun some of the ones with whom Wipperman butted heads in the ring, but that

was a long time ago, and people change. "I wasn't the easiest kid to train or talk to," he

says regretfully.

Dick Wipperman still doesn't wear a cowboy hat, but now if he did it'd be a white one.

> contents <

|