JULY

2007

01 | The Life and Times of

a Boxing Pioneer

By Enrique

Encinosa

02 | Poem of the

Month

By Colleen Aycock

03 | In the Ring with James J. Corbett : Book Sample

By Adam Pollack

04 | My Candidate for

Manager of the Year: Cameron Dunkin

By Adam Pollack

05 | Touching

Gloves with Ruben Navarro

By

Dan Hanley

06 | Flashback

to the 2006 World Boxing Hall of Fame Banquet

By Dan Hanley

07 | Why the Old Soviet

Block of Nations is having Success in Boxing

By Rocky Alkazoff

08 | "I'm from Down-Under

too" Reflections from IBHOF 2007

By Orion Foote

09 | Prelims:the Art &

Science of Matchmaking [pdf]

By Don

Cogswell

10 |

Boxing's Lineal Mathematics : Champion Versus Champion

By

Cliff Rold

|

The Life and Times of a Boxing Pioneer

by ENRIQUE ENCINOSA

Few men in history have laid claim to being pioneers that launched boxing in a

nation. There was James Figg in England, proprietor of the first boxing academy

making prizefighting the rage of the Fancy in the British Isles. There was

old-timer Bobby Dobbs, instrumental in popularizing boxing in Germany in 1910.

And there was John Budinich.

Even boxing historians shrug at the mention of the name. John Budinich is a

forgotten name in ring annals, yet he was a trailblazer whose sketchy and very

adventurous life deserves to be told.

John Budinich Taborga was born in Coquimbo, Chile, sometime in 1881, growing up

in a middle class background, his father being a merchant marine captain. As a

boy from a seafaring family he was groomed to be a naval officer.

An athletic teen, Budinich was mesmerized by boxing and tales of the ring, yet

the sport did not exist in Chile. There was interest in pugilism but the country

lacked skilled coaches or experienced fighters. Without trainers or fighters,

promoters could not exist. .

It was logical that boxing would start in a seaport town like Valparaiso, where

some of the British or American merchant mariners passing through had knowledge

of boxing basics. By 1897 the Colonel Urriola Athletic Club in Valparaiso

started to host amateur smokers in which local brawlers fought with more zest

than skills.

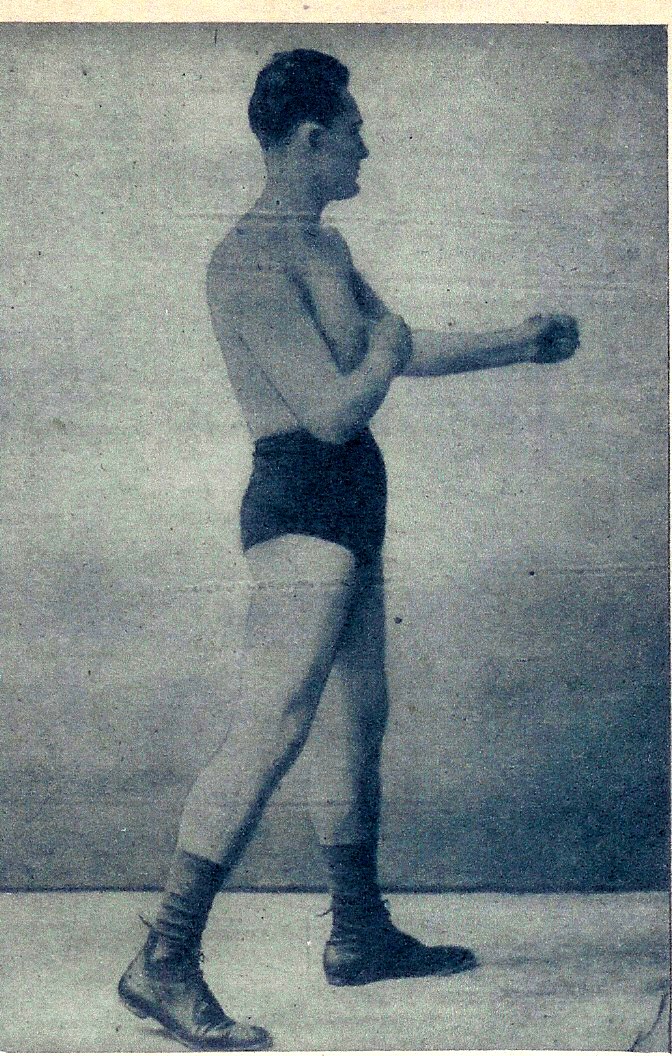

Budinich was one of the pioneer boxers at the Urriola Club but unlike most of

the warriors participating in the smokers, John had professional training. As

luck would have it, the naval cadet had struck a friendship with a blacksmith

named McDonald, who had some ring experience in his native Ireland, before

moving to Chile.

McDonald coached the naval cadet. The strapping teenager learned footwork,

jabbing, balance, honing his basic skills in dozens of sparring sessions with

his teacher at the back yard of the veteran fighter's blacksmith shop.

In his three years as a naval cadet, young Budinich also became the star

attraction at the Urriola Club smokers, consistently winning, outclassing the

brawling longshoremen, mariners and local youths who tried their luck in the

ring.

By 1902 Budinich had dropped out of the naval academy and opened up his own

boxing academy in the city of Santiago, in partnership with a transplanted

lightweight named Daly. He also worked as an English translator and sports

writer for the newspaper "La Union."

Encouraged by the fact that amateur boxing was developing in several cities in

Chile, Budinich decided to introduce professional boxing in his homeland.

The first pro boxing card in Chile was held at the Santiago Theater, where

Budinich made his pro debut by knocking out a British light heavyweight named

Frank Jones. A few months later, sometime in 1903, Budinich won a twenty rounder

on points over an American fighter named James Perry.

Twenty-two year old Budinich had achieved a measure of national fame in Chile,

being its first amateur and pro star. Most young men would have enjoyed their

local fame and never left Chile, content to be headlining club shows, running a

gym and working as a sportswriter, but John Budinich liked to travel.

He left Chile sometime in 1903, working on merchant boats until he reached New

York. The Chilean had a good knowledge of English that improved with practice.

He enrolled at Columbia University where he studied physical education. He

claimed to have paid for his studies working as a waiter, occasionally boxing in

prelim bouts and even being a sparring partner for the magnificent Philadelphia

Jack O'Brien.

"The most pleasant moments of my boxing career," Budinich said in an interview

years later, "were spent with that man. He was phenomenal in his ability…"

Indeed,

the cultured former naval cadet and university student did probably have the

personality to mesh well with the champion, for Philadelphia Jack was also from

a middle class background and was intellectually verbose and charming. Indeed,

the cultured former naval cadet and university student did probably have the

personality to mesh well with the champion, for Philadelphia Jack was also from

a middle class background and was intellectually verbose and charming.

After his university studies, the Chilean fighter continued his roaming ways. A

cargo boat took him to Europe and a merchant vessel brought him back; by 1908

Budinich landed in Colon , Panama, looking to fight a local hero named Sam Odon.

Panama was a busy country, where thirty three thousand workers toiled building a

historic canal across the isthmus. The many Americans and Europeans working on

the project had introduced boxing in Panama and Odon was one of the early local

heroes in the fight promotions, scoring several knockouts in crowd pleasing

fashion.

Budinich –at twenty seven years of age- was probably at his peak with over a

decade of ring experience under his belt; he was well conditioned and his sharp

mind understood the need of self promotion. As soon as he arrived in Panama, the

Chilean found and convinced several gamblers to back him betting on himself.

"In the very first round," Budinich said in an interview, years later, "I was

dropped to the canvas by a well timed blow."

Standing up, somewhat groggy, Budinich attempted to ward off the local light

heavyweight.

"I defended myself," he said, "and suddenly, I landed a right and to the floor

he went. From there on, I went full gallop."

The fight went the distance and the Chilean won on points, pocketing five

thousand dollars from his purse and the gamblers bets.

In 1910, John Budinich headed for Cuba, where he found a virgin territory for

his pugilistic ambitions.

Boxing in Cuba was non-existent. A couple of Cubans – Eugene Garcia and Emilio

Sanchez had boxed professionally in New York but had never fought in their own

country. Although boxing was not yet practiced, it was well covered by Havana

newspapers and tabloids of the time. The list of journalists that had covered

fights even included Jose Marti, the great Nineteenth Century writer and Cuban

nationalist, who was a ringside correspondent at the Sullivan-Ryan bare-knuckle

contest.

In a land without trainers or organized boxing, Budinich provided a desired

need. As in his native Chile, he became Cuba's boxing messiah. He set up shop in

Havana, renting a locale, setting up a ring and gym bags and printing flyers to

advertise the grand opening of Cuba 's first boxing academy.

Within weeks his boxing school was packed with eager young men willing to pay

gym fees and private lessons. The group of hopefuls included longshoremen,

construction workers, blacksmiths and a considerable group of well-bred

university students, the young sportsmen of Havana 's society set.

A cultured conversationalist, the Chilean also evidently possessed some social

skills, for within weeks of his arrival he was appointed boxing instructor at

the "Vedado Tennis Club," teaching the aristocracy how to jab. With a prosperous

gym and a salary at the country club, the enterprising prelim fighter was ready

for the next step in his career as a boxing impresario.

In order for boxing to progress, there had to be fights and paying audiences.

Budinich became a promoter, running amateur shows in the Actualidades Theater,

as well as in dance halls or even in private homes with large courtyards, where

he was also –very often- referee and sole judge.

In 1912, after promoting several amateur cards to small audiences, Budinich

announced his first pro boxing show at the Payret Theater in downtown Havana .

Since he was the only experienced pro in Cuba, Budinich announced that he would

not only promote, but would also fight in the main event star bout.

The Chilean was a good boxing teacher and a clever entrepreneur, but not a good

matchmaker. Instead of picking a soft opponent, Budinich brought Jack Ryan to

Havana . Ryan was a seasoned fighter who had traded leather with several top

fighters, including the magnificent Jack Dillon.

It took Ryan two rounds to knock out Budinich.

Budinich decided –for a while- to stick to training and promoting. He toured

several cities in Cuba with a crew of young fighters, fighting exhibitions. One

of his prospects was a heavyweight named Anastasio Penalver, proclaimed as the

new "Heavyweight Champion of Cuba," based on a few victories over other raw

novices.

Top American heavyweight John Lester Johnson was matched to fight Penalver in a

main event bout in Havana in 1915. The muscular but over matched Penalver was

stopped in the second round, towel thrown in by corner as Johnson pummeled the

Cuban.

Not content with one beating, Penalver faced Johnson in a rematch and was

stopped even faster. The Cuban heavyweight was not gracious in defeat, causing

an incident after the end of the fight card, when he threatened Johnson, using a

stone as weapon.

Budinich decided to return to the ring to avenge Penalver's fistic demise, but

first, he fought a draw against Jack Sentell, a durable and tricky club fighter

from Jacksonville , Florida.

John Lester Johnson was a fringe contender, one of a group of black fighters who

often fought each other in what was called the "Chitling Circuit." At the time

he fought Budinich, John Lester was a dangerous body puncher with solid skills,

destined to break Jack Dempsey's ribs in a future bout. Johnson stopped Budinich

in the very first round with a wicked body shot.

In five years Budinich had successfully introduced a sport in a nation. Although

none of his students attained international acclaim or contender status,

Budinich did train a crop of good local heroes, several becoming trainers and

gym owners after hanging up the gloves, including clever Victor Achan, tough

Mike Febles, lightweight slugger Tomas Galiana and feather weight Chau Aranguren.

By 1915, although other gyms had opened and an American named Brandt was new

competition in the promotional level, the Chilean was doing well. Budinich was

not wealthy but his income was enough to live in modest comfort. There was the

gym and the local pros he managed, plus his country club salary and a small

profit from promoting boxing shows at small venues. He married a Spanish woman

and many believed that he would stay in Cuba, involved in the development of the

sport, but the Chilean had a sense of adventure.

One day he left Cuba. Some claimed and newspapers printed the story that the

Chilean had decided to fight in the great epic in Europe, where men were

fighting in bloody trenches and tiny planes engaged in aerial combat over a war

torn land. It was announced that John Budinich had sold his gym and was off to

France, to wear the Kepi Blanc of the French Foreign Legion

Whether he did or not go to war, not much is known. John Budinich never returned

to Cuba and for a time it was believed that he had died in some forgotten

barricade, like Allan Seeger.

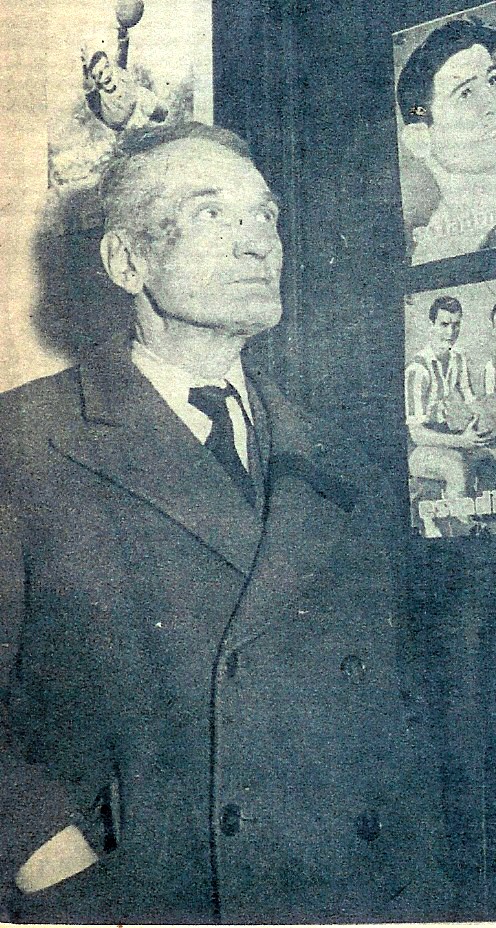

Luckily, the reports of his death were highly exaggerated. His ring career over,

Budinich returned to Chile with his wife, opening his third boxing academy, a

well run operation on the first block of Ahumada Street in Santiago. He became a

boxing instructor at Juan Enrique Concha University and was also in charge of

the boxing program for the Carabineri, the Chilean national police.

In 1945, the National Boxing Federation of Chile awarded him a well deserved

pension for his lifelong achievement in boxing.

After all, how many men can claim to have pioneered boxing in two different

countries.

contents

|