. . . THE CBZ JOURNAL

. . . THE CBZ JOURNALTable of Contents

. . . THE CBZ JOURNAL

. . . THE CBZ JOURNAL |

July 2001 Table of Contents |

|

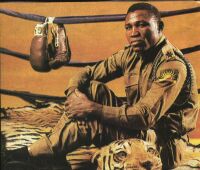

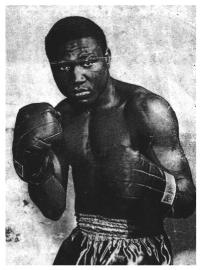

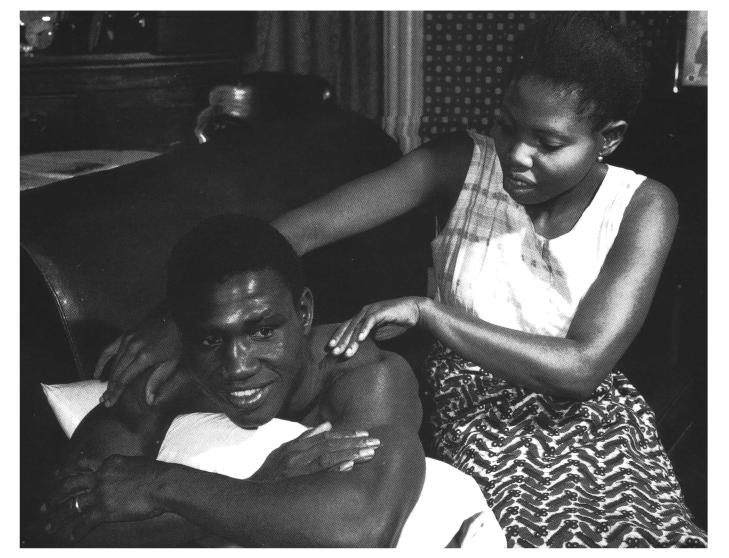

Dick Tiger -- Not a Visiting Apprentice From the soon to be published book 'Dick Tiger: The Life and Times of a Boxing Immortal by Adeyinka Makinde On May 22nd, with bag's and trunk's packed, Tiger and Abigail took a flight from Manchester bound for New York City. Awaiting him was his new manager, Wilfred 'Jersey' Jones, eager to supply him with some good news. Yes, his planned bout with one Rory Calhoun would be going ahead on June 5th at Madison Square Garden and after that there was the prospect that he could soon be fighting for the championship. The National Boxing Association was on the verge of withdrawing recognition from Sugar Ray Robinson and were considering staging an elimination tournament of the sort which he had managed to enter Hogan Bassey. Slightly built and gravel voiced, Jones was a youthful looking sixty-one year old with a varied but long time connection to boxing. He had seen the sport from both sides of the lens; first as a small time boxer in his native New Jersey and then as a press officer with Mike Jacobs Twentieth Century Sporting Club. Apart from handling a sprinkling of non-descript fighters, his vocation was in journalism, serving for many years as an Associate Editor of Ring magazine. Alongside Jones, Tiger hired the services of New York born Lou Burston, an atypical cigar-chomping impresario. Burston was a veteran in the fields of prize fighting and show business. A soldier during the First World War, he had hung around in Europe after demobilisation, settling down in Paris where he would build up a lasting network of boxing contacts on the European continent and French West Africa. During the 1920's, he developed his specialty business of importing fighters into the United States from areas in addition to Europe: the best known were the Puerto Rican Lightweight Pedro Montanez and the great Middleweight, Marcel Cerdan. His exotic connections perhaps unsurprisingly led to his involement the two best African imports; Hogan Bassey and then Tiger. Burston and Jones hired Jimmy August to serve as Tigers trainer, the role he had fulfilled during Basseys recent excursions into the American market. Of Lithuanian stock and confirmed bachelor status, August's world had revolved around the fight gyms and neighbourhood fight clubs of New York City ever since he had been invested with his trainers licence in 1922. While most of the fighters that he had seconded had being decidedly of the run-of-the-mill variety, his career was speckled with loose associations to a number of world champions. In the 1930's there had been a one-night stint handling the middleweight Ed 'Babe' Risko and a longer one with light-heavyweight Melio Bettina, a light heavyweight. In the 1950's, he began training a seventeen-year-old Puerto Rican, Carlos Ortiz, who later would develop into one of the great lightweights. Although one reporter assessed August as cutting the figure of a 'dumpy, white-faced man with a rather sad air, most were struck by his congeniality and quick wittedness. His working relationship with Tiger, while fraught by the occasional arguments, would be a good and fruitful one. Little more than a few days after his arrival, Tiger undertook his first training sessions on American soil at Lou Stillman's Gymnasium. Situated on Fifty-third Street this was the place for all the great champions - as well as the not so great. A daily procession of fighters walked up a straight flight of stairs and come to an open door from where two massive rings would be sighted. Over to the left, sitting on a stool would be Stillman himself. Above him hung a massive clock, the training clock. Working the bells round by round, all day long, Stillman would direct his guests to the 'appropriate.' A great fighter or a potential champion was designated ring one. "Lesser" fighters or those to whom he did not feel keen on were referred to ring two. Around the corner of the ring were the benches where all the fighters and champions from the newest aspirant to the great Sugar Ray Robinson would sit and wait their turns. Upstairs, the fighters could jump rope, punch the speed and heavy bags and indulge in callisthenics. Attired in trademark all-grey, the sweating, alternatively ferocious and smiling figure of Tiger became an establishment regular, sparring with the likes of Victor Zalazar, an Argentine middleweight and future opponent as well as the mob controlled Isaac Logart. This for Tiger was paradise. He was embarked on a learning mission not limited to his gym experiences: "In America" he later recalled, "I got good training and sparing, but, best of all I could go to many fights. I went to everyone I could. I watched and I learnt. The likes of Logart and Zalazar were he found "more rugged and durable" than most of the men he had faced in the professional ring. "They keep me constantly on my toes," he said, adding, "you can't sit down (because) they are always pushing; fighting." His brief experiences around New York gymnasiums gave him first hand insight in to why the American fighter was largely superior to his European counterpart: "It is the training," he told a writer who visited him at a Manhattan gymnasium a few days before the Calhoun fight, "rugged, constant training that does not stop when you leave the gymnasium. In my country, you do some roadwork and fight others who like yourself know just the bare fundamentals. But here in New York, my manager has paired me off with all kinds of sparring partners: the aggressive, strong type; the veterans who know all the tricks; the fast defensive boxer hard to hit. Outside the ring, you work just as hard jumping rope, punching the bag and doing exercises to build up your muscles and reflexes. Outside of the gym, you diet, learn to relax and live clean." This aptitude for learning would continue all through his career. Looking on, with August was Jersey Jones. Although impressed by Tigers grit and quiet confidence, he was quick to counsel August on those aspects of his game in need of 'improvement.' He acknowledged Tigers possession of a "fine left-hook" but the priority now, he felt, was for Tiger to develop his ability to throw effective punches to the body. Although this may have been a true enough assessment, Jones, it seems pertinent to note, had an exaggerated concept of the English game as being one in which the fighters were almost loathe to throw punches to the area below the neck for fear that they would be penalised for 'low blows.' "Things don't come quickly to him", he observed of Tiger, "But when he grasps them, they're here to stay." Tiger, he felt, needed "good, strong fights." Only by beating the topmost contenders would Tiger prove his credentials to an often times cynical American fight public which over the decades had grown accustomed to the 'horizontal' prone British fighter. Over the years, some fighters had come over to America from the British Isles on what might be termed 'visiting apprentiships;' that is on mini-tours designed to match them against available, top American opposition. Most of these ventures (and highly speculative they were) met with little success. Pat McAteer, Tigers nemesis, arrived a couple of years earlier as both national and empire champion to embark on a three-match tour. He lost all of them. Tiger was well tuned to the realisation that his Empire title counted for little in American circles. Ownership of the title for instance was not enough to grant him the world contenders' status that he craved. He was proud of his title and would make sure that journalists mentioned it, but he would never considered himself to be an atypical British fighter. As he once put it: "I am thankful to England for improving my language, but that's all. I never heard of defence until I saw England in 1955 (but) since then, the Britishers have gone the way of the American slam bangers - and so did I." America however did not provide him with all the answers related to fighting knowledge and Jones' comments about Tiger taking time grasp things may have alluded less to Tiger's lack of guile than to Tigers strident separation of the methods and tactic's that he felt were worth learning from those which he refuted. For instance, Tiger's view that he "copied" his opponent's style, that is, reacted to what his opponent did in the ring rather than try to impose his own tactic's, ran counter to the received wisdom taught in boxing gymnasiums. Later, when he was asked why he trained his sights on an opponent's gloves rather than on his opponent's eye, which boxer's are taught to do in order to predict the launch of their opponent's punches, Tiger famously retorted "nobody ever hit me with their eyes." The match with Rory Calhoun now came. It was the day Fidel Castro's five-month old regime announced the expropriation of the large-scale American interests in Cuban sugar mills and plantations. For the first of many occasions, Tiger stepped into the illustrious setting of Madison Square Garden. Someone informed him that the Garden, as was the case with Liverpool Stadium, had a cache of its own superstitions. A fighting debutant, one parable went, was liable to be 'bewitched, bothered and bewildered'. He smiled his usual sweet smile and set about his business. The fight itself turned out to be anything but a baptismal of fire. He impressed the curious Friday night crowd with a solid display of persistence and aggression. He consistently beat Calhoun to the punch, his salvo's inspiring intermittent applause. The decision ached, however, as the judges scoring it a draw. This however was unpopular with the crowd and with most of the fight reviewers. The rematch the following month at the Syracuse War Memorial Auditorium followed much the same pattern: Tiger was the dominant party in the exchanges, yet it ended in still more disappointment for him, this time a split decision loss. The crowd here was more demonstrative of its feelings than the Garden audience had been. Loud boo's echoed around the arena as fight programs and items of paper landed in Calhoun's corner. Tiger paused to take it all in. A draw and a loss were not the best of starts. In the recesses of his mind he may have begun thinking that this was Liverpool all over again. But he could find comfort in the fact that his performances were not at all bad. Jones proceeded on the basis that he would match Tiger with any of the available top contenders. There would be none of the calculated opponent picking typically indulged in by managers - there simply would be no time for that. Tiger was past his thirtieth birthday and no foreseeable route to a championship fight, it would be a question of him impressing the boxing fraternity by beating as many of the top contenders as he could lay his fists on and in effect 'force the issue.' His next couple of opponents bore this out. First was Gene Armstrong, rated fifth in the world rankings and so far unbeaten as a professional. The fight proved that August's lessons were bearing dividends. Tiger's efforts seem to be concentrated on mounting a persistent attack around the ribcage of his foe. He floored Armstrong in the third round -- the first time Armstrong had hit the deck in the 17 contests he had engaged in over a four-year period. Tiger's overwhelming points victory signalled his arrival into the official world rankings. Next came Joey Giardello, a seasoned campaigner, and like Tiger 'ageing' and anxious for a tilt at the championship. This would be the start of a series of four contests between both men. Nobody fought Tiger for as many rounds as did Giardello who has nothing but the fondest of recollections of the man: "When I first fought him I said 'Dick Tiger? Who the hell is Dick Tiger? They said 'You wanna fight Dick Tiger?' and I said 'I don't care but who is he?' I didn't know who he was but by the fifth, sixth round, I saw who he was! He was very, very tough and always in good shape. We won two fights apiece and I'm glad. I thought he was a gentleman. If you hit him low or something, he never, never put the baloney on. I always thought he was a great guy." Like his opponent, few in the Chicago Stadium audience were familiar with the name of Dick Tiger and even less with his fighting history. His introduction by the master of ceremonies barely elicited a response. Although he swung a fair amount of off-target left hooks, he landed enough solid blows to impress the judges enough to award him a unanimous decision. Then a set back. Jones accepted the rematch proposal from Giardellos managers and Tiger lost the decision. Many in the audience of the Cleveland Arena booed and whistled. Tiger sustained a rare cut, the result, he claimed, of Giardellos sneaky head butts. The crusade continued. Tiger won his next three bouts decisioning Holley Mims and Gene Armstrong at Chicago Stadium and then his erstwhile spar mate Victor Zalazar at the Boston Arena. They were all top-ten contenders and served as confirmation of the legitimate claim that he had to fight for one of the titles. Jones' entreaties however to Gene Fullmer, recent victor in the bout to determine the N.B.A's successor to Sugar Ray Robinson were rebuffed. The titled had now fractured. The middleweight division, even in times when the games sanctioning bodies appeared to operate with relative cohesion, now had two champions. Fullmer had garnered N.B.A. approval after beating Carmen Basilio in August of 1959, while Paul Pender, a fireman from Boston, won recognition from the state of New York and the European Boxing Union (E.B.U.), when he out pointed Robinson on January 22 1960. Pender, like Fullmer, was not interested in taking Tiger on, admitting to one sportswriter "Tiger is one of those fighters who just keeps coming. They are the kind you don't fight unless you have to." Tiger in the meantime was in the process of becoming one of the most recognised faces among American fight fans; this courtesy of the 'box.' It was still the era of saturation coverage. Although a number of the networks had stopped their telecasts; CBS and ABC had dropped their slots in 1955 while DuMont had gone out of business in 1958, NBC continued to broadcast its 'Fight of the Week' programme on Friday evenings. This partnership between boxing and television was one that would not have achieved the intensity that it did but for the influence of the International Boxing Club, a cartel headed by Jim Norris. After inheriting the monopoly that Mike Jacobs' Twentieth Century Sporting Club had held over the heavyweight championship, the IBC proceeded to fashion a stranglehold over much of the game and the agreements reached between Norris and the television companies served to buttress this grip. The consequences were decidedly in the negative. Many assert the malign influence of television in bringing in fickle audiences while robbing the neighbourhood clubs and local arenas of their natural constituency. Even the Garden suffered: In 1950, the year in which the IBC was inaugurated, attendances had averaged 8,849 per bout, but by 1959, they had plummeted to 2,371. Fighters purses were hit also, although ironically, Tiger would only have noticed the great improvement American wages were when compared to the almost derisory sums he had only recently being earning in England. The $6,500 earned from the Calhoun fight exceeded every single payment he had received from British promoters. That bout had been covered by NBC and at the end of 1959, all six of his bouts had being televised, more than any other fighter, save the ubiquitous Mexican welterweight, Gasper 'Indian' Ortega. However, Tiger ranked twelfth in the end of year top fighter poll that was headed by Sonny Liston. His English fans caught up with his progress on the BBC's Saturday afternoon sports case, Grandstand, avidly devoured all of Tigers fights. One newspaper journalist however spotted a drawback to the television exposure to the Americans: Each succeeding performance, while strengthening his title claims, heightened the threat that he posed to the champions. Hogan Basseys passage to a championship shot was decidedly the easier since he was relatively unknown to his foes. With Tiger, it was perhaps a case of the potential opposition knowing too much about him too soon. He and Abigail set up home in a small suite in the Colonial Hotel, a modest establishment situated in Manhattans Upper West Side district. He would continue to patronise this place, on and off, for the next decade. The rooms were sparsely furnished and they cooked their meals on a hotplate. Abigail, who had left Liverpool in the early months of her first pregnancy gave birth to a set of twins in September 1959, in the week that he faced Giardello. The boy and girl were christened Richard Chimezie and Grace. Tiger would go on record as stating his preference for America to England, one British journalist quoting him as saying that he did "not like England." New York City, with its glamorous skyscrapers, the green expanse of Central Park (which would form a constant training patch for Tiger) and its overall amenities shaped up to be more than a few rungs above Liverpool. Abigail found Americans to be more open and friendlier. On occasion after finishing his training at Stillmans, Tiger would meet up with his old foe, Patrick McAteer, who was now settled in the States with his American born wife. "We had a few coffees at the Madison Square Garden cafeteria and enjoyed each others company" McAteer recalls. "Stillmans gym was up on 58th Street, the Garden was down at 50th Street and right across the street on Eigth Avenue was the Garden cafeteria. We'd talk about old times in Liverpool, we'd look at the girls and say 'How 'bout that cutie over there.' His accent was strange to the Americans, (but), I think everybody respected him. It was hard not to respect Dick. He was a nice guy, patently just a nice guy." Americans were indeed fascinated by the 'short, chunky man with blue tribal tattoo's etched across the knotty muscles of his chest and back.' A curiosity piece, in the ring as well as out of it, Tiger would provide the sports hacks of New York with a steady amount of copy. His image, the like of which they had not seen before, was striking: A dark skinned African man frequently sighted with a trademark homborg hat and Anthony Eden coat. They wrote often of the incongruity of on the one hand his tribal marks and on the other, the formal, quasi-Anglicised accented speak. Throughout his career, he endured a seemingly never ending ritual of questions and commentary about the African continent by Americans, journalists and others, intrigued by popular tales of the 'dark continent'. Wrote Milton Gross, the syndicated sports columnist in the wake of Tigers death: 'He listened and patiently tried to answer some of the stupid questions put to him by boxing reporters. To many of us insulated and isolated in what had been our affluent society, Tiger was a curiosity from a world which few of us understood or really tried to understand_He tried to explain the geography, economics and language of his country'. To little apparent avail. Tiger, Gross observed, however, did not succumb to emotional outburst, writing that he would occasionally 'be annoyed by our inanities, sometimes amused but never angry.' It became part of the daily grind and he developed a repertoire of responses. To those who presumed that his moniker related somehow to exploits in the great jungle, he informed that 'there are no Tigers in Africa - only in Asia' and 'I never saw a Tiger until I looked at one in Liverpool zoo.' If we are to believe comments made in the later part of his career, Tiger accepted what he termed his 'Tarzan image' because it made for good business at the box-office. In 1962 he told Nat Loubet that he considered the jokes and the banter about jungles and, cannibals and headhunters as "good-natured joshing". So when people asked him what he had eaten for breakfast, he replied with exaggerated flourish "Hew-mon Bee-inks, medium rare." On the occasion when a very largely built New York City policeman visited his training camp, he was asked if Nigerian constables were that large. Smilingly he replied, "Oh sure, 'cause for breakfast, they eat guys like him." The incessant queries about cannibalism prompted the quip that "We quit that years ago when the Governor-General made us sick." There were occasions, however, when his response did not refer to humour. Days after the infamous slaying of black civil rights martyr Medger Evers, he referred to the "cannibals who shoot you in the back." The reality all along was that Tiger was offended and in certain instances felt quite aggrieved by these jokes. The level of ignorance with which he was confronted disappointed him. In 1965, he would go so far as to announce that he would refuse under any circumstances to be photographed standing near trees. He began correcting Americans when they spoke in unconsciously patronising ways. When for instance a person referred to "the natives" of his homeland, he was quick to interject with "people". There were instances when he was sorely tested and found it necessary to direct sharp comments towards the likes of Jones and August when he felt that their words were out of order. Another area that journalists seized upon -and with a good measure of justification, was Tigers perceived frugality this, a reputation immortalised by Charlie Goldman's quip that "Dick Tiger wouldn't pay a quarter to see an earthquake." Tiger, they wrote, had a penchant for inexpensive suits which one journalist would describe as being akin to 'Salvation Army hand-me-downs.' The recollections of Sam Toperoff in a Sports Illustrated article about a walk in the company of Tiger around Manhattan prove illuminating. "His brown suit," wrote Toperoff,"was on the shabby side, the jacket a shade lighter than the pants; his black shoes had grey scruff's." After Tiger despatched a parcel at a post office, both men stopped in front of a tailors shop. As Toperoff relates, "He went inside and I followed. He pulled off his suit jacket and showed the man behind the counter a long tear in the satin lining. The owner persuaded Tiger that it would be better to select a second hand jacket from the racks in the rear than to have his own jacket repaired. Tiger and the tailor disappeared. When they returned, Tiger was wearing another brown jacket, a shade darker than the pants this time. The man wanted $5. They settled on $2.50, his old jacket and a ticket to the (Rocky) Rivero fight." "He was always considered a very tight man with money and intimacies" wrote Robert Lipsyte in 1969. And Les Matthews, a columnist with the New York Amsterdam News recalled that Tiger "enjoyed walking because it saved money." "He was a very frugal guy"' recalls Gil Clancy, trainer of Emile Griffith, "You know, he's still wearing the same old winter overcoat for about three years despite how much money he made. He'd send it all back to Nigeria; he was a very stolid, steady guy." "He always wore that same overcoat and hat" remembers Tommy Kenville, a publicist at Madison Square Garden. "I don't think that he ever bought another overcoat or hat in his life." But Tiger was steadfast in refusing to measure his worth in this manner. "Clothes will not make me a better man or a better fighter" he once reposted. "Which is more important -how I dress or how I fight (and) look after my children?" On other occasions a wit and down-to-earth practicality came through. Once, after he had won the championship, Jones and others were ribbing him about his penny-pinching ways. Now that he was a champion, they suggested that he buy his wife a mink fur coat. "Guys" he replied, "I told you that I was from Nigeria, not Siberia." Ron Lipton, a friend and sparring partner will hear nothing of claims of 'tightness.' "I don't think its true," he says. "He knew that some day, the boxing would be over and he was somewhat afraid that he wouldn't earn a decent living. I don't think he was tight with money because he didn't spend it on himself. I think he really took care of his family and I couldn't stand anyone saying he was cheap. He was a very decent, generous person." Many were struck by the outwardly calm demeanour referred to by Gross and he exercised great restraint in the face of a great many provocations. But like any other man, he was capable of the odd angry mood. "Dick did have a little bit of a temper," Lipton recalls. "It wasn't a screaming temper but his face would change. See, if he got upset his whole body and face would change. You knew when he was upset with someone because he was always smiling, so when you saw him cloud up like that, you knew like you better step away from him for a while. I was sitting next to him at the Johnny Persol-Henry Hank fight in 1964 and then somebody walked by and mentioned something about one of the middleweights, 'Oh, he'll kick your ass' or something like that. He was smiling at me and then he looked up. I could see the change in the face. He knew that it was just a stupid fan but you could see (him thinking) 'I'd like to hit this guy a left hook.' He would never do that but I'd say 'There it is.' I was always wondering what would push his button." Impressions of the man would over the years develop into a positive one. For if Battling Siki, the first world champion from the African continent, epitomised crude, stereotypical notions of the inarticulate savage, filled with sexual and social malevolence, then the genteel restrained bearing of Dick Tiger represented his antithesis. Tiger, like Hogan Bassey, placed great emphasis in projecting images of gentlemanly refinement that was reflected in the way they spoke and dressed. "I would say Sir, that Mr. Pep has most unusual idea's about the rules", Bassey told a startled sportswriter when questioned about the unorthodox (read: illegal) tactics the former featherweight champion had employed against him during their 1958 non-title bout at Madison Square Garden. Tiger's characteristic reticence though, contrasted markedly with Basseys natural ebullience and his quietness led some, like Joey Giardello, to believe that he was unable to speak the English language, at least in the earlier stage of his U.S. career. He had been campaigning there for five years when after his bout with Rubin Carter, a group of New York writers went up to the English boxing broadcaster, Reg Gutteridge, to ask if Tiger spoke any English. Later, in Tigers dressing room, Gutteridge informed him of the query: "Womba,womba Mr.Ihetu, they want to know you speaka English?" Grinning widely, Tiger quipped: "Tell them much better than they do" Tiger barely had time for rest between his fights. In the ten months elapsed since arriving in America, he fought on eight occasions. He decided that it was time for a break. After fighting Victor Zalazar in April 1960, he took Abigail and the children to Aba. Jones announced at the time that Tiger would not fight for the next "two or three months". He was finding it hard to set up fights for Tiger. He told the British press that Tiger had been "quite excited" when Mickey Duff had sent word of his willingness to stage a bout with Terry Downes, but that no more had been heard from Duff. A couple of weeks after Tiger's departure, Jones received news of an edict issued thousands of miles away in London by the Empire Championships Committee ordering Tiger to defend his Empire title, dormant for two years since he had won it from Patrick McAteer, within 'three months' failing which they would declare the title vacant. Jones was approached soon after by a consortium of Canadian businessmen headed by a promoter, Moe Gundersson. They reached a tentative agreement for Tiger to defend the title against Wilf Greaves, the Detroit based Canadian Middleweight champion and gold medal winner six years earlier at the Empire Games held in Edmonton. Jones then entered into a verbal contract with Greaves' manager, one C.W. Smith, a tool-manufacturing magnate, under which Tiger and Greaves would split 60% of the proceeds from the gate. Tiger would receive the larger share. Tiger arrived from Nigeria in late May to put his signature to the agreement. He arrived Edmonton Airport on June 15th, with August in tow. He smiled for local Pressmen as he posed with a soft toy Tiger perched on his luggage. Then he made his way to the city's luxurious Airlines Hotel, which would serve also as a training camp. He retired early and was up the following morning at 6 to commence roadwork. In the afternoon, he spared with a local fighter called LeRoy Flammond before completing a routine set of exercises. He kept this up until the weekend. The local press, eagerly covering the fight build up, hungrily gathered titbits on the stranger in their midst's. In his column for the Edmonton Journal, Tom Harris wrote that Tiger 'speaks English amazingly well, carries a good conversation which he punctuates with wide grins and an intense look of concentration, and has a penchant for goulash and spaghetti.' Harris, perhaps was unaware that Tiger came from an English-speaking nation. But while Harris' impressions of Tigers speaking ability were high, some of his colleagues preferred to quote him using an accent more appropriate to a Tarzan movie. At a photo session at the Airlines hotel kitchen, a writer asked Tiger which parts of the menu he wanted to eat. Tigers reply was quoted as 'I not want dessert now. We feed piece like that to cat back home.' On the Monday afternoon that preceded the Wednesday fight date, Tiger had to abandon plans for his last scheduled work out. Instead, at Gunderssons instigation, he visited the local racetrack in order to promote the bout, which was being plagued by slow ticket sales. The sixth race of the day was named the 'British Empire Purse' and Tiger dutifully presented the winning jockey and trainer with tickets for the fight. The crowd of 3,360 spectators who turned up at the Edmonton Exhibition Gardens was well below the 9.000 Gundersson had envisaged. Tiger fought tentatively: He had never been scheduled to go fifteen rounds. Not even Greaves' obnoxious pre-fight promise to chase him out of the ring "all the way back to that homestead of his in Nigeria" appeared to have riled him enough to make a faster start. This gave Greaves the edge in the early stages. But Tiger rallied as the bout wore on and ended the bout with him subjecting the Canadian to immense pressure. When it was over, referee Johnny Smith and the judges, Louis Schwartz and Les Wilcox handed their scorecards to the officials representing the Edmonton Boxing Commission. They were tabulated and the decision was announced as a draw. Tiger had retained his title. Or so he thought. Few eyebrows were raised at the verdict. The crowd remained calm while the outward expressions of Greaves and his handlers betrayed to onlookers no more than the usual disappointed countenance. The spectators were beginning, slowly, to drift out of the arena and two journalists working for the Edmonton Journal, sports editor Hal Pawson and boxing correspondent Tom Harris were eager to join in the exodus. Pressed against them as they struggled to get out of the congested press row area, were two top officials of the commission. Pawson turned in the direction of the commission table where before his eyes lay the fight scorecards. He recounted the subsequent happenings in his 'Sporting Periscope' column in the next day's edition of the paper: 'The check was not so much intentional as impossible to avoid (with) the four of us squeezed so closely together by the mob around ringside. It was help with the cards or the pickpockets; we were that jammed. 'It was only a matter of seconds before we realised something was wrong with the decision as announced. Dr. Louis Schwartz's card, for instance, was marked and announced as nine to six rounds in favour of Tiger. One glance made it plain that something was wrong, for at least six rounds stood out as even. 'The quick recheck showed that judges card really to be six rounds for Tiger, three for Greaves and six even. That called for further investigation. Dr. Les Wilcox's card came out as announced, seven rounds for Greaves, five for Tiger and three even. 'That left it up to the recheck of (Johnny) Smiths card. It came out on first quick check as six rounds for Greaves, four for Tiger and five even. However, it was sweat soaked and blood smeared and later checking with Johnny, it boiled down to one round, which at first glance appeared even being in Tigers favour, making the final count six for Greaves, five for Tiger and four even. His points came out as seventy to sixty nine for the home boy.' Excited by their discovery, Pawson and Harris sought C.W. Smith who then informed Graham of the discrepancy. Graham now called members of the Edmonton Commission to an emergency meeting, the secretary, William 'Spud' Murphy took hold of his briefcase and scrambled for a copy of the organisations rulebook. Quick to get wind that something was wrong, Jones began running towards Graham and his colleagues, shouting, as he approached. He was told to wait alongside C.W. Smith until they finished with their deliberations. Referee Smith, Schwartz and Wilcox where all summoned and asked to recheck their scorecards. Half an hour passed before the door opened. Jones and C.W. Smith were called in and informed that the original decision would be set aside and that Greaves would be declared the winner of the contest. Jones protested but to no avail. Quoting from the rulebook before him, Graham explained that no decision was official until the commission ratified it -even if, as had been the case here, it had been announced in the ring. The new decision was relayed to members of the press, still camped around the arena, one hour after the fight ended. The decision threw Tiger. An air of bewildering unreality pervaded the dressing room. He brooded for a time before emerging to speak to the journalists waiting outside. "I've never heard anything like it" he said, voice betraying more than a hint of stunned incredulity. "It doesn't make sense. I thought it was close and that I got the worst end of the verdict. But at least, that would have meant that I kept my title. Now this happens." It was bizarre. So typically unlucky. He arrived in New York, his mind racked with a sense of injustice. These feelings would intensify over the months because of Greaves' subsequent conduct. The contract with Greaves contained a clause stipulating a return match within ninety days if he lost the match and Jones had already announced that it would take place in Edmonton, "despite what they have done to us." Gundersson pencilled in a provisional date of August 26 but this was quickly rescheduled for September 14 after Greaves pleaded a training injury. Stunning news followed: Without giving any reasons, Greaves announced that he was pulling out of the fight. He surfaced later to announce that he would be meeting Obdulio Nunez, a Puerto Rican middleweight, in New York claiming that he was using the bout as a 'tune up' for the defence of his Empire title. Tiger was mortified. He agreed with Jones that beating Greaves and regaining the title would be the priority. Jones announced that "All these postponements are costing him money" and referring, perhaps, to the imminent arrival of another child in September, he added, " He's got a family to support and the money has got to come from somewhere." He wrote to the B.B.B.C. urging them to suspend Greaves until he fulfilled his obligation to Tiger. He also contacted the commission in Canada who proceeded to advise the New York authorities not to sanction the Nunez bout that had been scheduled for October 15. New York obliged and suspended Greaves. This forced C.W. Smith into meeting Jones and concretising arrangements for his fighter to face Tiger in November. With only hour's left to the proposed bout with Nunez, the New York State Athletic Commission relented and restored Greaves' licence. Greaves lost the bout on a split decision. At precisely 9.55 pm on Thursday, November the 24th, a chilly Canadian winters day, Tigers plane arrived at Edmonton International Airport. The first words he uttered to the waiting pressmen concerned his loathing of snow. His mood got darker when an officious Customs Officer proceeded to hold him up for an hour while he decided whether Tiger should pay a toll on his used boxing gear. He made it plain that Greaves' had offended him. "It makes me angry inside." he told one reporter, "For five months I haven't worked, waiting for this one." In all, Jones reckoned that Greaves' prevarications had cost Tiger "up to $30,000" in lost income. Greaves, for his part, was dismissive, saying: "I can't bleed for Dick Tiger because his camp didn't know enough to get him fights while I was out with bad ribs. If it cost him $30,000, his camp should answer to him", adding, "The title is better off in Edmonton where it will do more good than in Nigeria." The papers would focus on the feud between Tiger and Greaves, picking on the most innocuous of happenings to confirm this 'hostile animus.' Both men were camped at the Kingsway Hotel, with Tiger training at 6.pm and Greaves following at 7 and reporters watched, hawkeyed for any problems: 'There is still animosity between the two parties, both upset at developments since the last meeting' one report began. 'For instance, over the weekend, Tiger had finished his workout and Greaves entered the downstairs banquet hall to begin his hours training. Tiger and trainer Jimmy August were still there and Greaves refused to begin until the opponents had left.' Tiger's preparations were not limited to the relatively cosy surroundings of the Kingsway Hotels basement. Roadwork had to be done in the bitingly cold Canadian winter. He ran through early morning temperatures of ten degrees below zero. By the time he arrived back at the hotel, icicles were formed on his forehead. This, he concluded to himself was worst than what he'd experienced in Chicago. Damp and muggy Liverpool simply did not compare. The Edmonton Gardens had only 2,500 spectators on the night of the fight, the promotion on this occasion, having largely being overshadowed by the Grey Football Cup. This time, Tiger was better prepared to meet the challenge of a fifteen round bout. August had had a good look at Greaves' style and proposed that Tiger would break him down sooner by utilising a three punch combination move: Throw a jab and follow up with a right cross and left hook. It worked well. In the third, he rocked Greaves with a crushing right hand to the jaw and by round eight, his blows had inflicted deep gashes above both of Greaves' eyes. Greaves' condition worsened in the next round, Pawson writing, that the Canadian was 'glassy-eyed, his jaws slack, mouth agape and his face punched somewhere over the vicinity of his right ear.' Tiger had him pinned in a corner when, John Smith, refereeing again, stepped in to wave the fight over. This did not accord well with one outraged ringside spectator. "You donkey Smith," he wailed, "you can't stop a title bout until you count the bum out on his back." There was a decidedly vindictive ring about Tigers post fight chortle that he had merely being "warming up" when Smith intervened. It had, nevertheless, being a great performance, one which Jones would later acknowledge had convinced him that Tiger was not just a 'tough, good middleweight who could give anybody trouble' but was a fighter of depth and facility. If he held this form, he would be champion. A mix of frustration and resentment had fuelled the punches that Tiger had thrown at Greaves. The bruised knuckle he discovered after unwrapping the gauze, needed time to heal. This meant that the bout which Jones had arranged with Hank Casey, scheduled to take place on December 14th in New Orleans, had to be aborted. Gundersson, apparently recovered from the dismal revenues from the Tiger-Greaves fight which had being poorer than the first bout, announced that he had started negotiations with Gene Fullmers manager with the view to staging a championship contest in Edmonton. Nothing, however, was to come of this; Fullmer signed to fight Sugar Ray Robinson in March 1961. Hopes raised temporarily after he out pointed Gene Armstrong in a third meeting when Robinson, as was characteristic of the later part of his career, threatened to pull out after a dispute over money. Jones quickly offered Tiger as a substitute opponent, but the matter was settled. The garden next matched Tiger against his old foe, Spider Webb. After beating Tiger in 1959, Webb went on to make an unsuccessful world title challenge; a point's loss to Gene Fullmer. He retired to join the ranks of the Chicago police Force but agreed to face Tiger fourteen months later at New York's St.Nicholas Arena. Tiger stopped him in the sixth. A New Orleans based promoter, Lou Messina, now revived tiger's fight with Hank Casey, held in abeyance since December. Tiger signed the contract, but Casey decided to stay put in California. Jones scrambled around for a replacement. One missive was sent to Joey Giardello's handlers. But there was an obstacle here -New Orleans, a city at the heart of Southern culture, had no record of an interracial boxing match since George Dixon, the black featherweight champion defeated his white challenger, Jack Skelly. Blacks could fight other blacks on the same bills as whites but could not engage white fighters. It is inconceivable that Jones, a noted boxing historian, would have been ignorant of this and he was perhaps issuing a mild challenge to the mores of a region, which at the time were being assaulted by the bourgeoning civil rights movement. He had in fact approached Rory Calhoun's handlers "in case there is any trouble." As things turned out, Casey relented and Tiger won a split decision. Tiger continued to be ignored by both Fullmer and Pender. The former had been inactive since his March win over Ray Robinson and Tiger, as the number three-rated contender to the title, expected to get the nod to challenge him. Instead Fullmer bypassed him in favour of Florentino Fernandez, ranked at number seven. He got nowhere with Pender who haven beaten the ageing Carmen Basilio now signed for a rematch with Terry Downes. Pender was booked to fight in July while Fullmer's engagement was scheduled for the following month. His career thus plunged into stagnation; Tiger turned his mind to other matters. He decided that the time was apt to resettle his family in Aba. Although the press releases mentioned Abigail's 'homesickness' and the difficulty of bringing up children in a hotel suite, she still did find living in America quite appealing. Tiger, however, was insistent and they all left for home in June. While in Nigeria, Tiger began the first of his ventures into the property market. He found time for family, friends and the community but there appear to be few discernable hobbies or pursuits outside of boxing and business: "My mother used to say that he was so dedicated to his profession and she didn't know of any," says his son Charles. "There was nothing in particular like say playing tennis. He would hang out with friends, his brothers and extended family." Family and community meant a great deal to Tiger. His brothers and their families enjoyed his largesse: he financed the university education of two nephews and never forgot to dispense gifts to relatives. A few years later, George Girsh of the Ring would write: 'Every time Dick Tiger fights in the United States, he spends a few days relaxing around the pawn shops of the area in which he happens to be, especially if it's New York. He buys gifts for his numerous establishments -(mother), wife, six children, cousins, uncles, aunts_. When he returned to Nigeria after winning the light-heavyweight title from Jose Torres, he took back enough gimcracks, jewellery and what not to incur an average of $175 in air charges. The truth worth of a man in the traditional Igbo society is determined not solely by his ability to enrich himself materially, but, also in his aptitude in cooperating with the wider community for their collective betterment. The deeds of Dick Tiger reflected this and over the next few years he would aid several projects within the Amaigbo community. 'Handsome contributions' were made towards the building of a hospital and postal agency. And when the village market, schools and churches needed reconstructing, he was on hand to dig deep into his pockets. Tiger's absence form the rings did not go unnoticed. It moved one Frank Shields in New Orleans to write to the Ring and bemoan the scenario of a fighter of Tiger's calibre and popularity being 'allowed to escape from the United States and return in disgust to his native Nigeria because he isn't given the what he so richly deserves -a chance at the world middleweight title.' Jones cabled him at the beginning of October to tell him of a bout that the Garden had lined up for him with the Cuban, Florentino Fernandez, who's challenge of Fullmer had being unsuccessful. Tiger arrived at the end of the month to begin training for the December date. Fernandez, however, sent word from Cuba that the post-revolutionary conditions were preventing him from leaving the island. His replacement, Billy Pickett, a popular campaigner around his native New York and Eastern Canada, was beaten by a huge points margin. Tiger finally met Fernandez on January 20th in Miami. The city had already become the focal point for Cuban's fleeing the Castro regime. The local convention Hall, filled with most of Fernandez's compatriots, throbbed to the sounds of the joyous Salsa beat that a band of supporters played between rounds. Tiger absorbed a few and blocked many of the murderous punches Fernandez lobbed at him before replying in kind. He broke the Cuban's nose in round five and his trainer, Angelo Dundee, prevented him from answering the bell for round six. In a rare burst of exuberance, Tiger turned to the band to raise his hand and dance a hip-swaying jig. He journeyed to his dressing room with the sound of an ovation ringing in his ears. Next came a match against Henry Hank, the fifth ranked middleweight. Hank possessed an exceptional strength of punch, among his thirty-six knock out victims was a light-heavyweight contender named Jesse Bowdry whom he had stopped two months earlier in New Orleans. Tiger's contest with Hank was billed as a duel between 'uncrowned champions.' Although a foreign boxer, he was by now recognised as what Harry Markson, the Director of Boxing at the Garden, described as a 'stand out fighter'; so much so that the Garden now remunerated him with a $10,500 television appearance fee that more than doubled the average fee of around $4,000. The Garden drew seven and a half thousand spectators who witnessed a surprisingly one-sided affair. Only in the inaugural round did Tiger have to contend with anything resembling meaningful opposition: Both men exchanged jarring hooks to their faces but Tiger surprised Hank with a two stiff right hand leads which landed on his nose. Jolted, Hank countered with two left hooks. Tiger shrugged them off and came back with a short, right to Hanks head before following with a powerful sally of left hooks. Hank emerged for the second, a changed fighter. When Tiger walked to him, he backed away. At other times, he shuffled hesitantly, tightening his stance, as if waiting to land one of his trademark haymakers. Tiger hit him almost at will, but he also defended well. The shots that Hank aimed at his head, he intercepted with his gloves, while his arms blocked those strikes that were destined for his mid-riff. By the end of the bout, Hanks had according to the watching New York Times correspondent, being 'hit with just about every type of punch that is legally permissible or imaginable in the prize ring.' Tiger's dominance had been so complete that referee Arthur Mercante scored every one of the ten rounds in Tiger's favour. The two judges could only award Hanks a round each. What more, Tiger thought, would he have to do in order to get that title shot?

|

Dick Tiger Joey Giardello Emile Griffith Nino Benvenuti |

| Schedule | News | Current Champs | WAIL! | Encyclopedia | Links | Store | Home |